- Home

- Diane Duane

My Enemy My Ally Page 10

My Enemy My Ally Read online

Page 10

"Commander," he said, "I make you no promises, but you're beginning to interest me. Tell me 'our story.'"

"Why, only this," she said, smiling back at him; "that Cuirass, which I command—at least it will seem to be Cuirass, for I have a copy of that ship's ID solid aboard Bloodwing, ready to be installed—that Cuirass detected Enterprise violating our space, and followed her out into the Zone, where she attempted to bring us to battle, but suffered mechanical difficulties—which I suspect your Chief Engineer, whom we also know well, can fake without too much difficulty. That, unable to run, and with damage to your warp engines, we had only to draw you into exhausting your firepower, and then wear your shields down with fire of our own, to reduce you to a position where you (with your well-known compassion for your crew) were left helpless enough to be unable to repel a boarding action. With your Bridge taken and your crew under the threat of having your own intruder-control systems used on them—a swift killer, that gas—you surrendered the ship to buy their lives. My crew manned control positions on your ship, placed her in tow, and headed for home."

It was plausible. It was even doable. "There have been other ships in the area, though," Jim said. "Anyone tracing your iontrail and ours would also note the passage of first Intrepid, then Constellation and Inaieu—"

"True. But it's difficult to accurately place such residues in time, is it not? Their decay is not regular, especially in the space hereabouts, where you have noticed the weather has been bad lately." Ael tipped her head to one side, regarding Jim. "And by the time anyone follows our trails out this far and returns within subspace radio range of Levaeri V, it will be too late. We will already have done what we came for. Enterprise and Bloodwing will break away from the escort, if any—"

"You mean take them all on and blow them up?" McCoy said incredulously. "How many ships come in an escort, anyway?"

"For Enterprise, they would hardly send fewer than two. Four, at the most, would be my guess."

Bones looked incredulously from Spock to Jim and back again. "We're just going to 'break away' from four fully-armed Romulan cruisers, probably those Klingon-model cruisers—"

"You gentlemen will not fail me," Ael said, perfectly calm. "This is the Enterprise, after all. . . . Once we have scrapped the escort, destroying Levaeri V should not be too much of a problem."

"I imagine not," Jim said. "But, Commander, what about the loss of life?"

"The Romulans doing the research have not been too concerned about that," Ael said coolly, "especially where the Vulcans have been concerned. I did not think that would be so much of an issue for you. Perhaps I miscalculated."

"Perhaps." Jim thought of about seventy things he wanted to shout at her, none of which would have done him or her any good; this woman might look almost Earth-human, but he had to keep reminding himself that their respective branches of humanity had very different mores indeed. "Mr. Spock," he said after a little while, "opinions?"

Spock looked distinctly uncomfortable. "Commander," he said, turning to her for a moment, "I would ask you not to take anything I say as a slight against your honor."

She bowed her head to him, the gracious gesture of nobility to one almost a peer. Jim started to get very annoyed.

"Captain," Spock said, "the plan is an audacious one. Its odds for success in its early stages are very high. However, I advise you most strongly against it. There are too many variables, unknowns, things that can go wrong at the plan's far end. Even should one of our allies suggest such an operation, having a spare Romulan ship with falsified ID on hand, Starfleet would have no mercy on the plan if it miscarried. And with the suggestion coming from a representative of a power with whom the Federation has long been on the fringes of war—"

"Amen to that, Mr. Spock," McCoy growled. "Whole thing's a pack of nonsense."

"No, Doctor," Spock said, eyeing him, "that it is not. The Commander's plan is excellently reasoned—but the risks in its later stages become unacceptably high. For a Vulcan, at least. Captain?"

Jim looked at Ael. "You say that you are willing to forego pride for the time being," he said. "Then I hope you'll pardon me, but this has to be said. How do we know you're not lying? Or worse—how do we know you haven't been brainwashed into thinking this is the truth you're telling us, so that you can safely lay your honor on the line?"

Ael breathed out once, leaving Jim to wonder whether a sigh meant the same thing to Romulans as it did to his branch of humanity. "Captain," she said, "of course you had to say that. But there is a way to find out, one that strikes to the heart of this whole matter. Ask Mr. Spock if he will consent to subject me to a mindmeld."

Jim looked at Spock. Spock was still as stone. "It's true," McCoy said. "There are ways of blocking or tampering with a mind that won't show up under verifier scan—but will in mindmeld. It would be conclusive, Jim."

"I had thought of it," Jim said. "But I didn't want to suggest it." And he said nothing more.

A few seconds went silently by. Finally Spock looked at Ael and said, very quietly, "I will do this, Commander." He glanced over at Jim. "Captain, somewhere more private would be appropriate."

"Your quarters?"

"Those would do very well. Commander, will you accompany me? The Captain and the Doctor will join us shortly."

"Certainly."

Out they went together, the Vulcan and the Romulan, and Jim had to stare after them. There was something so alike about them—not just the racial likeness, either. "Well, Bones," he said, "get it off your chest."

McCoy leaned forward on the couch, elbows on knees, and stared at Jim. "How much I have to get off," he said, "depends on what you're going to do."

"Nothing, until we have Spock's assessment of what the inside of her mind looks like."

"And what if she is telling the truth, Jim? Are you tellin' me you're going to go off on some damn fool chase into interdicted territory, probably get us surrounded by Romulans again like the last time—but this time on purpose? We're just going to sit there and be towed into Romulan space under escort! Why don't we just tie ourselves up and jump out the airlocks in our underwear? Save us all a lot of—"

"Bones," Jim said, not angrily, but loudly; sometimes when McCoy got started on one of these it was hard to stop him. Bones subsided.

"I am not seriously considering it," Jim said. "Even if she is telling the truth. What I'm trying to figure out is what to do about what she's told us. This information is too sensitive to do anything but whisper in a Fleet Admiral's ear; I wouldn't dare send it via subspace radio, buoy, or any other means that might be intercepted, decoded, anything. Too much rests on it—as far as that goes, she's not understating. None of the ships can leave the task force, and I'm sure as Hell not going to send an unarmed shuttlecraft or one of Inaieu's little couriers off with it. Plus I have other problems on my mind." He reached out to the table and hit one of the 'com switches on it. "Bridge. Mr. Scott."

"Scott here."

"Scotty, how're our Romulan friends?"

"Quiet as mice, Captain. Back on their original course, holding steady at warp five and one lightsecond."

"Any communications?"

"None, sir."

"Very well. Give me Uhura."

"She's offshift, sir," said another voice. "Lieutenant Mahasë."

"Oh. Fine. Mr. Mahasë, call the Romulan ship. My compliments to Subcommander Tafv, and we are still conferring with the Commander. No progress to report as yet, should he inquire."

"Right, sir. By the way, Captain, we have another message from Intrepid."

"Live message, or canned?"

"Canned, sir. They left it recorded in a squirt on the satellite zone-monitoring station we just passed—NZRM 4488. The ion storm was holding steady at force six; they expected it to begin tapering down any time. Sensors still show a lot of lively hydrogen up that way, though. We'll be running into it ourselves shortly."

Jim rubbed his eyes. Damn weather … "Well, keep trying to reach them in realtime

—they ought to be appraised of what's going on back here. Anything else I should know?"

"Mr. Chekov wants to take just one shot at Bloodwing, Captain. Just for practice."

"Tell him to go take a cold shower when his shift's over," Jim said. "Kirk out. Come on, Bones, let's go see if the truth really will out."

Nine

Ael followed Spock silently through the corridors of Enterprise, trying to understand the people walking those corridors by studying their surroundings. She could make little of what she saw, except that she found it vaguely unpleasant. The overdone handsomeness of the Transporter Room and the ridiculous luxury of the Officers' Lounge had put her off; she had found herself thinking of her bare, cramped quarters in Bloodwing with ridiculous nostalgia, as if she were hundreds of light-years away from it, marooned in Cuirass again. But the situation was really no different. Here as there, she thought, I am among aliens—and if what I plan succeeds, I will have to live so for the rest of my life. I had better get used to it. And she followed Spock into his quarters expecting something similar—something Terrene-contaminated, overdone, something that would make her even more uncomfortable than she already was.

But she got a surprise. For one thing, the room was warm enough to be comfortable. For another, except that they were bigger, the quarters might have been a twin to her own for the general feel of them. The place was utterly neat; sparsely furnished, but not barren; and if it accurately reflected its owner, she was going to have to revise her estimation of Vulcans upward.

There were some things there, such as the firepot-beast in the corner, that she knew enough about Vulcans not to inquire of; like a good guest she passed them by. But other things drew Ael's attention. One was a stereo cube, sitting all alone on the ruthlessly clean desk. In it a dark stern Vulcan man stood beside a beautiful older woman, who wore a very un-Vulcan smile. Ael put out a hand to it, not touching, thinking of her father. "This would be Ambassador Sarek, then," she said, "and Lady Amanda."

"You are well informed, Commander," Spock said. He had been standing behind her, not moving—holding very still, as Ael fancied someone might who had a dangerous beast at close range and did not want to frighten it.

She laughed softly at his words, and at her own thoughts. "Too well informed for my own comfort, perhaps." She turned from the portrait toward the wall that adjoined the panel dividing the sleeping area from the rest of the room, and looked up at the very few old weapons adorning it … and breathed in once, sharply.

"Mr. Spock," she said, "am I mistaken? Or is that, as I think, a S'harien up there?"

The look in his eyes as she turned to face him was not quite surprise—more appreciation, if that closed face could be said to express anything at all. "It is, Commander. If you would like to examine it …"

He trailed off. Ael reached up with great care and took the sword down from the wall, laying it over the forearm of her uniform so as not to risk fingerprinting the exquisite sardonyx-wood inlay of the scabbard. The sheath's design was lean, clean, necessary, brutal logic and an eye for beauty going hand in hand. The hilt was plain black kahs-hir, left rough as when it had been quarried, for a better grip: logical again. "May I draw it?" she said.

Spock nodded. Whispering, the steel came out of the sheath. Ael looked at it and shook her head in longing at the way even a starship's artificial light fell on the highlights buried in the blade. No one had ever matched the work of the ancient swordsmiths who had worked at the edge of Vulcan's Forge, five thousand years before; and S'harien had been the greatest of them all. The pilgrims to ch'Ríhan had managed to take five of his swords with them. Of those, three had been broken in dynastic war, shattered in the hands of dying kings and queens; one was stolen and lost, thought to be drifting in a long cometary orbit around Eisn; one lay in the Empty Chair in the Senate Chambers, where no hand might touch it. Certainly Ael had never thought to hold a S'harien. The sword in her hand spoke, by its superb balance, of things Ael couldn't say; of history, and home, and treasures lost forever; of power, and the loss of it, and the word there was no one to tell. . . .

She looked up at the Vulcan in unspeakable envy and admiration, her voice gone quite out of her. A fine showing you're making! Ael thought bitterly. Struck dumb by a piece of metal—

"It is an heirloom," he said, as if sensing her momentary loss. "It would be illogical to leave it locked in a vault, where it could not be appreciated."

"Appreciation," Ael said, in a tone that was meant to be light mockery; but her voice shook a bit. "That's an emotion, is it not?"

He looked at her, and Ael saw that without meld, without the use of touch or anything else, Spock still saw her nervousness with perfect clarity. "Commander," he said to her, innocently matching her tone, "'appreciation' is a noun. It denotes the just valuation or recognition of worth."

She stared at him dubiously.

"I believe you are telling the truth," he said. "And if you are, I cannot say how much I honor you for daring to do what you have done, for peace's sake. But for both the Captain and myself, belief will not be enough. We must be utterly certain of you and of what you say."

"I understand you very well," Ael said. "Understand me also; I have given up pride—though not yet fear However, I demand that you do to me whatever will best convince the Captain."

Spock lifted his head, hearing footsteps in the hall. Ael, considering that it might not be wise for the Captain to come in and find her facing his First Officer while holding a sword, gave Spock a conspiratorial glance and turned her back on him, savoring the feel of the S'harien in her hand for just a moment more. . . .

The door-buzzer sounded. "Come," Spock said quietly. In came the Captain and the Doctor, and as the door shut behind them, they stood uncertainly for a moment, looking at Ael. She turned to face them, and her fear fell away from her at the bemusement on the Doctor's face, the surprise on the Captain's.

"Gentlemen," she said to them, picking up the S'harien's scabbard from the desk and sheathing it again, "I had no idea that the Enterprise would be carrying museum pieces. Can it be that all those stories about starships being instruments of culture are actually true?"

And to her utter astonishment, she saw that her cautious flippancy was not fooling the Captain, either. He was looking at her with the small wry smile of someone who also knew and loved the feel of a blade in the hand.

"We like to think so, Commander," he said. "You should come down to Recreation, if there's time … we have some interesting things down there. But right now we have other business." And he glanced at Spock much as Ael might have glanced at Tafv when there was some uncomfortable business to be gotten over with quickly.

She bowed slightly to him, sat down in the chair at Spock's desk. The Vulcan came to stand behind her. Ael leaned back and closed her eyes.

"There will be some discomfort at first, Commander," said the voice from above and behind her. "If you can avoid resisting it, it will pass very quickly."

"I understand."

Fingers touched her face, positioning themselves precisely over the cranial nerve pathways. Ael shivered all over, once and uncontrollably; then was still.

Her first thought was that she couldn't breathe. No, not that precisely; that there was something wrong with the way she was breathing, it was too fast. . . . She slowed it down, took a longer deeper breath—and then caught it back in shock, realizing that she couldn't take that deep a breath, her lungs didn't have that much capacity—

Do not resist, her own voice said in her head without her thinking any such thing. Surely this was what the approach of madness was like.

No! They are breaking faith with me, they are going to drive me mad—no! No! I have too much to do—

Commander—Ael—I warned you of the discomfort.

Do not resist or you will damage yourself—

—oh, bizarre, the words were coming in Vulcan but she could still understand them—or rather she heard them at the same time in Rihannsu, and in F

ederation Basic, and in Vulcan, and she understood them all. Her own voice speaking them inside her, as if in her own thought—but the thought another's—

Better. Our minds are drawing closer. . . . Open to me, Ael. Let me in.

—impossible not to; the self/other voice was gentle enough, but there was a strength behind it that could easily crush any denial. Would not, however—she realized that without knowing how—

—closer now, closer—

—Elements above and beyond, what had she been afraid of? What an astonishment, to breathe with other lungs, to see through another mind's eye, to journey through another darkness and find light at journey's end. . . . That was no more than she did on Bloodwing, than she had done all her life; how could she possibly fear it? She reached out for the other, not knowing how: hoping will would be enough, as it had always been for everything else—

—we are one.

She was. Odd that there were suddenly two of her, but it seemed always to have been that way. With the odd calmness of a dream, where outrageous things happen and seem perfectly normal, she found herself very curious about the events of the past few months, the whole business regarding Levaeri V, from beginning to end. Luckily it took little time, in this timelessness, to go over it all; and she took herself from beginning to end in running commentary and split-instant images—the crimson banners of the Senate chambers, the faces of old friends in the Praetorate who solemnly said "no," or said "perhaps" meaning "no." There were the faces of her crew, glad to see her back, outraged nearly to rebellion at the thought of her transfer from Bloodwing. There were the hateful faces of the crew of Cuirass, and there was t'Liun's voice shouting over ship's channels for her to come to the Bridge. There was Tafv, dark and keen, reaching out to take her hand as she boarded Bloodwing again, raising her hand to his forehead in a ridiculously antique and moving gesture of welcome. And her cheering crew, all of them like children to her, like brothers and sisters. There was Bloodwing's Transporter Room. And there was another Transporter Room entirely, with men in it. One fair and lithe, with an unreadable face and a very unalien courtesy; one dark and fierce-eyed, with hands that looked skilled; and one who could have been one of her own brothers, if not for Starfleet blue, and the memory of old enmities . . . .

The Book of Night With Moon

The Book of Night With Moon A Wind From the South

A Wind From the South A Wizard Abroad, New Millennium Edition

A Wizard Abroad, New Millennium Edition Lior and the Sea

Lior and the Sea Uptown Local and Other Interventions

Uptown Local and Other Interventions High Wizardry New Millennium Edition

High Wizardry New Millennium Edition Games Wizards Play

Games Wizards Play Wizard's Holiday, New Millennium Edition

Wizard's Holiday, New Millennium Edition So You Want to Be a Wizard, New Millennium Edition

So You Want to Be a Wizard, New Millennium Edition The Door Into Sunset

The Door Into Sunset To Visit the Queen

To Visit the Queen A Wizard Abroad

A Wizard Abroad Not on My Patch

Not on My Patch The Door Into Shadow

The Door Into Shadow The Door Into Fire

The Door Into Fire A Wizard Alone New Millennium Edition

A Wizard Alone New Millennium Edition The Tale of the Five Omnibus

The Tale of the Five Omnibus The Wizard's Dilemma, New Millennium Edition

The Wizard's Dilemma, New Millennium Edition The Big Meow

The Big Meow Wizards at War, New Millennium Edition

Wizards at War, New Millennium Edition Interim Errantry

Interim Errantry Omnitopia: Dawn

Omnitopia: Dawn High Wizardry

High Wizardry Spider-Man: The Venom Factor Omnibus

Spider-Man: The Venom Factor Omnibus Spider-Man: The Venom Factor

Spider-Man: The Venom Factor Seaquest DSV

Seaquest DSV How Lovely Are Thy Branches

How Lovely Are Thy Branches So You Want to Be a Wizard

So You Want to Be a Wizard Midnight Snack and Other Fairy Tales

Midnight Snack and Other Fairy Tales Stealing the Elf-King's Roses

Stealing the Elf-King's Roses Interim Errantry 2: On Ordeal

Interim Errantry 2: On Ordeal Raetian Tales 1: A Wind from the South

Raetian Tales 1: A Wind from the South Starrise at Corrivale h-1

Starrise at Corrivale h-1 The Wizard's Dilemma

The Wizard's Dilemma Sand and Stars

Sand and Stars How Lovely Are Thy Branches: A Young Wizards Christmas

How Lovely Are Thy Branches: A Young Wizards Christmas On Her Majesty's Wizardly Service fw-2

On Her Majesty's Wizardly Service fw-2 X-COM: UFO Defense

X-COM: UFO Defense Star Trek: The Original Series: Rihannsu, Book 5: The Empty Chair

Star Trek: The Original Series: Rihannsu, Book 5: The Empty Chair seaQuest DSV: The Novel

seaQuest DSV: The Novel Stealing the Elf-King's Roses: The Author's Cut

Stealing the Elf-King's Roses: The Author's Cut Not On My Patch: a Young Wizards Hallowe'en Story

Not On My Patch: a Young Wizards Hallowe'en Story A Wizard Alone yw[n&k-6

A Wizard Alone yw[n&k-6 The Bloodwing Voyages

The Bloodwing Voyages Games Wizards Play (Young Wizards Series)

Games Wizards Play (Young Wizards Series) The Book of Night with Moon fw-1

The Book of Night with Moon fw-1 My Enemy My Ally

My Enemy My Ally Dark Mirror

Dark Mirror Star Trek: The Original series: Rihannsu: The Bloodwing Voyages

Star Trek: The Original series: Rihannsu: The Bloodwing Voyages Deep Wizardry yw[n&k-2

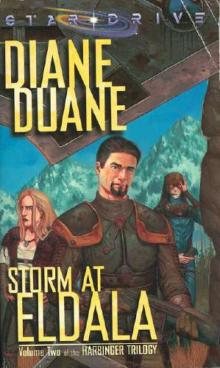

Deep Wizardry yw[n&k-2 Storm at Eldala h-2

Storm at Eldala h-2