- Home

- Diane Duane

My Enemy My Ally Page 11

My Enemy My Ally Read online

Page 11

Her sudden curiosity invited her to look more closely at those enmities. She resisted at first—they were old history, and their consideration bred nothing but anger. But the curiosity wouldn't be balked, and finally Ael gave in to it. That image of her sister's-daughter standing before the Senate after her defeat at the Captain's and Spock's hands, after the loss of the cloaking device to the Federation. Ael's impassioned, desperate defense of her before the Senators—useless, fallen on hearts too obsessed with vengeance and fear for their own places to hear any plea. Ael stared again down the length of the white chamber, looking toward the Empty Chair, while around her the voices proclaimed her sister-daughter's eternal exile from cn'Ríhan and ch'Havran, the stripping of her honors from her, and worst, the ceremonial shaming and removal of her house-name. Ael had protested again at that, not caring how it would endanger her own position. The protest had gone unheeded. She stood at marble attention while the name was thrice written, thrice burned, and watched bitterly as her sister-daughter went from the chambers in the deepest disgrace—no longer even a person, for a Rihannsu without a house was no one and nothing.

And where is she now? she cried to that curious, silent part of her that watched all this. Wandering somewhere in space, or living alone on some wretched exile-world, alone among aliens? How should I not hate those who did such a thing to her? Nor was there any forgetting Tafv's bitter anger at the exile of his cousin, his dear old playmate. Yet he had come to know cool reason, as Ael had, just as this sudden new part of her had learned it when he was young and occasionally angry. Hate would have to wait. Perhaps some kind shift in the Elements, at another time, would allow her a chance to face her enemies and prove on their bodies in clean battle that they were cowards, who had consented to deal in trickery to achieve their means. Now, though, she needed those enemies badly. Personal business could not be allowed to matter where the survival of empires was involved.

The new part of her agreed silently and said nothing more for a moment. Ael seized that moment, for she had her own curiosity. Here was one of those enemies, inwardly linked to her. Becoming "curious" in turn, she reached out to it; and the other part of her, in a kind of somber acknowledgment of justice, suffered her to do so. Ael reached deep—

She had for years been picturing some kind of monster, a half-bred thing without true conscience or sense of self, the kind of person who could work a treachery on her sister-daughter with such cool precision. But now, as in her estimate of what his rooms would be like, she found herself wrong again, so very wrong that her shame burned her. Certainly there was the vast internal catalogue of data and store of expertise that she would have expected from a man whom even among the Rihannsu was a legend as one of Starfleet's great officers. But what she had not suspected was someone as torn as she was, and as whole as she was, and in such similar ways. Someone who had sworn himself to a hard life, for what seemed to him a greater good more important than his own, and who had suffered for the oath's sake, and would again, willingly; someone who was also powerfully rooted in another life, a heart's life—based around a planet where he could hardly ever walk, and relationships he could never fully acknowledge, because of what he had chosen to be. No oaths were attached to those choices—just simple will, rock-steady and unbreakable. That person she had not suspected. Alien he might be, but there was that very Rihannsu characteristic, the unshakable, unbreakable loyalty to an idea, a goal, a man who embodied it. The best part of the ruling Passion, a banked fire, but burning this man out from within, and never to be relinquished, no matter how much it hurt—

That man she could open to, as she might open to Tafv or Aidoann or tr'Keirianh. And she did, feeling suddenly for the terrible suppressed passions in him, and for one of them more than any of the others—for homesickness. She showed him Airissuin, and the barren red mountains of her home, so like his own; she showed him the farmstead, and the place where the hlai got out, and her father, so very like his; the small dry flowers on the hillside, and the way the sunlight fell across her couch the day after her son was born, and she held him in her arms for the first time without the distraction of pain, wishing his father had lived to see—oh, Liha, lost to the Klingons in that ridiculous "misunderstanding" off Nh'rainnsele! Could there never be an end to such misunderstandings—worlds to walk safely, an end to wars, other ways to avoid boredom and find adventure? Must the innocent die, and must she keep on killing them? An end to it, an end!

Her second self was in distress; but so was Ael, and for the moment she had no pity on either of them. This was after all the most important matter, the only one that ranked with truth and hearts and names. Life must go on, and with the implementation of the project at Levaeri, there would be an end to it. Truth would become deadly, hearts would become public places, and names—Better that small wars should flare up and take their inevitable toll, better that she and Tafv and all the crew of Bloodwing, yes, and that of Enterprise too, should die before such a thing happened. For these were honorable people, as she had always suspected and now found that she had not known half the truth of it. Just the image of the Captain that her otherself held was enough to convince her; his image of the Doctor, very different but held in no less loyalty, was more data toward the same conclusion. Such people, whatever her hatreds, hinted at the existence of many more on the other side of the Zone. They must not be allowed to become obsolete, or dead, as honorable people everywhere would should this technique be carried to its logical conclusion; they must not, they must not—

—and her mind abruptly came undone. Not a painful sensation, but a sad one, as if she had been born twins and was bidding the twin good-bye.

Ael opened her eyes. The Vulcan she could still feel behind her—some thread of the link apparently remained; she could feel the stone-steady foundations of his mind shaken somewhat. But of more interest to her was the look the Captain was giving her, both compassionate and bleak. The Doctor was turned toward the wall and rubbing his eyes, as if something ailed them. She realized abruptly that her face was wet.

Spock came around from behind her, his hands behind his back, physically standing at ease; but Ael knew better. "Commander," he said quietly. "I apologize profoundly for the intrusion."

"I thank you," she said, "but the apology is unnecessary. I am quite well."

Glancing up at him, she saw that Spock, also, knew better. The Captain was looking from one to the other of them. "I also apologize, Commander," he said. "If it will do any good …"

"It will do none to the exiled or the dead," Ael said, as levelly as she could, wondering how much she and the Vulcan might have spoken aloud in this meld, and fearing the worst. "But for myself, I thank you."

"If you would excuse us a moment," the Captain said, "I must discuss this business with Mr. Spock and Dr. McCoy."

She bowed her head to him; they went out into the corridor together, all three moving as separate parts of one mind. We are more alike than I imagined, she said to herself, rubbing briefly at her face and thinking of those times in battle and out of it when she and Tafv and Aidoann functioned as one whole creature in three different places. If I am not careful, I will forget to hate these people for what they did to my sister-daughter … and what will become of me then?

"Captain," she distinctly heard Spock saying, "every word she has told us is the truth. She is under no compulsion save that of her conscience—which is of considerable power; her resolve and fear of lost time was what broke the link—I did not."

"Any sign of tampering with her mind at all?" the Captain said.

"None. There were areas I could not touch, as there might be in any mind. And one piece of data with unusually powerful privacy blocks around it—an area somewhat contaminated with emotions that I consider similar to human types of shame and regret. But my sense was that this was a private matter, not concerning us."

"I don't like it," the Doctor said. "Did you get a 'sense' of any associational linkages to that block that might reach into the are

as that do concern us?"

"Some, Doctor. But this blocked material had linkages to almost every other part of the Commander's mind as well. I do not think it is of importance to us."

"Well," said the Captain, and let out a long breath. "Spock, I hate to say this, but Fleet is not going to buy what the Commander's proposing. It's too farfetched, too dangerous, and even though the Commander is an honorable woman, I can't possibly trust all those other Romulans. She tells us herself that the Romulans as a whole are becoming more opportunistic, less attached to their old code of honor. What do we do if some one of them, while aboard the Enterprise, gets the idea to try a takeover? Granted that we outnumber them incredibly—if so much as one of my crew should die in such an incident, Starfleet would have my hide. And rightly. I agree with her that we have a moral responsibility to the three great powers—out if we tried to carry off the operation she suggests, and then botched it somehow so that word of what's going on at Levaeri leaked out without our managing to destroy the place—No. I'm sorry. Strategically it's a lovely idea, but tactically, with our present force and numbers, it's a wash. I am going to send for more ships—quietly—and then act."

The Captain let out another unhappy breath. "Come on, gentlemen. Let's tell her the bad news as gently—"

The small viewer on Spock's desk whistled. "Bridge to Captain Kirk."

Ael reached out to flick the small switch beside it. "If you will hold one moment, I will get him." Mr. Spock, she said through the rapidly fading mindlink, would you please tell the Captain he has a call?

A flash of acquiescence reached her. The door hissed open, and in the three came again. "Sorry to keep you waiting, Commander," the Captain said. "Let me handle this first. Kirk here," he said to the viewer.

"Captain," said the communications officer, a gray-skinned hominid who had apparently replaced the lovely dark woman Ael recalled from Tafv's earlier call to Enterprise, "we have another squirt from Intrepid. They were passing by NZR 4486 when they were apparently attacked."

"By what?" the Captain said, glancing sharply at Ael.

"That's the problem, sir. They didn't know. The ion storm suddenly escalated to nearly force-ten—enough to leave them sensor-blind. It was just after that that they were fired upon. But the odd thing is that they didn't fall out of communication with the relay station until almost a minute and a half after the storm escalated. Then they just cut off communication in the middle of transmission—not a storm-fade, or a catastrophic loss of signal, as if they'd been—as if something had happened to the ship. Just a stop."

"Keep trying to raise them, Mr. Mahasë. And call red alert. All hands to battle stations. Alert Inaieu and Constellation; they're to go to red alert as well."

"Aye aye, sir. Any further orders?"

"None at present. Kirk out."

Outside Ael could hear the ship's odd red-alert siren whooping, and people hurrying past the room. "Commander," the Captain said, "what do you know of this?"

"That the attacking ship is almost certainly Rihannsu," she said, "and the ion storm almost certainly our doing. I wish you had told me of this earlier; I have had no news of it from my ship. Unfortunately your sensors seem to be rather better than ours—"

"What do you mean the ion storm's 'of your doing'?" the Doctor said.

"I am sorry, gentlemen," she said, "but it is hard to tell you everything presently happening in Rihannsu space while standing on one foot. Mr. Spock, if you look into your memories of our meld, you will find this information accurate. One research that has been complete for some time now is a method for producing ion storms by selective high-energy 'seeding' of stellar coronae. The High Command has been using it for some time as a clandestine weapon to keep the Klingons from raiding our frontier worlds. Their economic situation has been very bad recently, as you may know, and their treaty with us has been honored more in its breach than in its keeping. However, the technique has also been used on this side of the Zone—to cover the tracks of those who have been stealing Vulcans. How better to spirit away small ships, without anyone noticing, than to have them vanish in ion storms? Everybody knows how dangerous those are—"

"Then the change in the stellar weather hereabouts," Spock said, "has not been natural, but engineered."

"To some extent. There was some concern that changing it in one place would also cause changes elsewhere; so the climatic alterations of which you speak may be secondary rather than primary. However, things now look even worse than they did, gentlemen. The research at Levaeri must be even further along than I thought, for the researchers to take such a large group of Vulcans—and right out from under the noses of a Federation task force. They must be about to start production of the shifted genetic material in bulk, to need so wide a spectrum of live tissue." Ael looked grave. "Captain, if you do not do something, shortly half the Imperial Senate will be reading one another's alleged minds, courtesy of the brain tissue of the crew of the Intrepid . . . ."

Spock stood still, appearing unmoved—but again Ael knew better; and the other two stared at her in open horror. "Commander," McCoy said at last, "this is ridiculous! If the Romulan ship tries to capture the Vulcans, they'll die sooner than let that happen—"

"They will not be allowed to die, Doctor," Ael said, becoming impatient. "Don't you understand yet that this technique not only reproduces in its users the mental abilities of trained Vulcans, but raises those abilities to a much higher level than normal? What use would it be making touch-telepaths out of the Senate? Who among them would allow anyone to much him? The technique was designed to enable mindreading and control at a distance for short periods—even control over the resistant minds of Vulcans already knowledgeable in the disciplines! Three or four people aboard a Romulan ship could easily hold the Bridge crew of Intrepid under complete control for the short time it would take to make them stop firing, lower their shields and be boarded. Or there are other methods equally effective. Then the Rihannsu would simply take ship, Vulcans and all across the Zone, under cover of the ion storm, and do their pleasure with them."

"But Vulcans with command training—" the Captain said.

"Command training will make no difference to this artificially augmented ability, Captain," Ael said. "We are dealing here with an ability that if developed much further will be able to take on even races as telepathically advanced as the Organians and Melkot."

The Captain's face went very fierce. "We've got to go after them—"

"You cannot. If you do, you and your whole crew will suffer the same fate as Intrepid—one not so kind, actually. Your minds will fall under control far more swiftly than those of Intrepid's Vulcans did—and after the Rihannsu move in and arrest you and Spock and the Doctor, they will kill your crew and take the Enterprise home to study. The same thing will happen if Inaieu or Constellation follow you in. No, Captain, if you want the Intrepid and its crew back, my plan is the only way. And we will have to be swift about it. They will not wait around, at Levaeri, now that they have the genetic material they need. Processing of the Vulcans will begin at once."

Ael sat still, then, and watched the Captain think. A long time she had wanted to see this—her old opponent in the process of decision, ideas and options flickering behind his eyes. And it was very quickly, as she had suspected it would be, that he looked up again.

"Commanader," he said, "I think, for me moment, you've got an ally. Spock, have Lieutenant Mahasë call Rihaul and Walsh. I want a meeting of all ships' department heads in Inaieu in an hour. Bones, bring Lieutenant Kerasus with you."

"Yes, Captain."

"Right, Jim."

And out they went. Ael found herself alone and looking at an angry man—one who was going to have to do something he didn't want to, and was very aware of it.

"Commander," he said to her, "am I going to regret this?"

"'Going to'? Captain, you regret it already."

He frowned at her—and at the same time began to smile.

"Let's go," he

said.

Ten

It turned into the noisiest staff meeting Jim could remember in many years of them. The number of people in attendance was part of the reason—all eighteen of Enterprise's department heads, along with Janíce Kerasus from Linguistics, Jim's Romulan culture expert, and Colin Matlock, the Security Chief; and the Captains and department heads of both Constellation and Inaieu. There they were, crammed into Inaieu's Main Briefing … hominids and tentacled people and people with extra legs, all three kinds of Denebians and very assorted members of other species, in as much or as little Fleet uniform as they usually wore.

In the middle of all the blue and orange and command gold and green was a patch of color both somberer and more splendid; Ael and her son Tafv, both in the scarlet and gold-shot black of Romulan officers. They did not bear themselves like two aliens alone among suspicious people. Ael sat as unshaken among them as she had in the Officers' Lounge; and Jim, looking across at the calm young Tafv leaning back in his chair, decided that he had inherited more from his mother than his nose.

He had beamed across from Bloodwing at Ael's request, and had looked around Enterprise's Transporter Room with the hard, seeing eyes of someone checking an area for weaknesses, assessing its strengths. Jim had looked curiously at him, wondering how old he really might be; for Romulans, like Vulcans, showed little indication of aging until they were in their sixties. The man looked to be in his mid-twenties, but might have been in his forties for all Jim knew. Then he found himself being examined closely by those eyes, so pale a brown they were almost gold; an intrusive, disconcerting stare. "Subcommander," he had said, and courteously enough the young man had bowed to him; but Jim went away disquieted, he didn't know why.

The Book of Night With Moon

The Book of Night With Moon A Wind From the South

A Wind From the South A Wizard Abroad, New Millennium Edition

A Wizard Abroad, New Millennium Edition Lior and the Sea

Lior and the Sea Uptown Local and Other Interventions

Uptown Local and Other Interventions High Wizardry New Millennium Edition

High Wizardry New Millennium Edition Games Wizards Play

Games Wizards Play Wizard's Holiday, New Millennium Edition

Wizard's Holiday, New Millennium Edition So You Want to Be a Wizard, New Millennium Edition

So You Want to Be a Wizard, New Millennium Edition The Door Into Sunset

The Door Into Sunset To Visit the Queen

To Visit the Queen A Wizard Abroad

A Wizard Abroad Not on My Patch

Not on My Patch The Door Into Shadow

The Door Into Shadow The Door Into Fire

The Door Into Fire A Wizard Alone New Millennium Edition

A Wizard Alone New Millennium Edition The Tale of the Five Omnibus

The Tale of the Five Omnibus The Wizard's Dilemma, New Millennium Edition

The Wizard's Dilemma, New Millennium Edition The Big Meow

The Big Meow Wizards at War, New Millennium Edition

Wizards at War, New Millennium Edition Interim Errantry

Interim Errantry Omnitopia: Dawn

Omnitopia: Dawn High Wizardry

High Wizardry Spider-Man: The Venom Factor Omnibus

Spider-Man: The Venom Factor Omnibus Spider-Man: The Venom Factor

Spider-Man: The Venom Factor Seaquest DSV

Seaquest DSV How Lovely Are Thy Branches

How Lovely Are Thy Branches So You Want to Be a Wizard

So You Want to Be a Wizard Midnight Snack and Other Fairy Tales

Midnight Snack and Other Fairy Tales Stealing the Elf-King's Roses

Stealing the Elf-King's Roses Interim Errantry 2: On Ordeal

Interim Errantry 2: On Ordeal Raetian Tales 1: A Wind from the South

Raetian Tales 1: A Wind from the South Starrise at Corrivale h-1

Starrise at Corrivale h-1 The Wizard's Dilemma

The Wizard's Dilemma Sand and Stars

Sand and Stars How Lovely Are Thy Branches: A Young Wizards Christmas

How Lovely Are Thy Branches: A Young Wizards Christmas On Her Majesty's Wizardly Service fw-2

On Her Majesty's Wizardly Service fw-2 X-COM: UFO Defense

X-COM: UFO Defense Star Trek: The Original Series: Rihannsu, Book 5: The Empty Chair

Star Trek: The Original Series: Rihannsu, Book 5: The Empty Chair seaQuest DSV: The Novel

seaQuest DSV: The Novel Stealing the Elf-King's Roses: The Author's Cut

Stealing the Elf-King's Roses: The Author's Cut Not On My Patch: a Young Wizards Hallowe'en Story

Not On My Patch: a Young Wizards Hallowe'en Story A Wizard Alone yw[n&k-6

A Wizard Alone yw[n&k-6 The Bloodwing Voyages

The Bloodwing Voyages Games Wizards Play (Young Wizards Series)

Games Wizards Play (Young Wizards Series) The Book of Night with Moon fw-1

The Book of Night with Moon fw-1 My Enemy My Ally

My Enemy My Ally Dark Mirror

Dark Mirror Star Trek: The Original series: Rihannsu: The Bloodwing Voyages

Star Trek: The Original series: Rihannsu: The Bloodwing Voyages Deep Wizardry yw[n&k-2

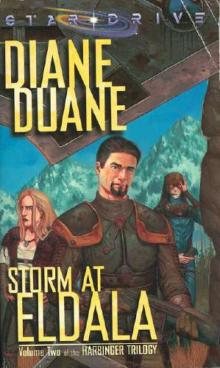

Deep Wizardry yw[n&k-2 Storm at Eldala h-2

Storm at Eldala h-2