- Home

- Diane Duane

A Wizard Alone yw[n&k-6

A Wizard Alone yw[n&k-6 Read online

A Wizard Alone

( Young Wizards [= Nita & Kit] - 6 )

Diane Duane

Kit and Nita join forces once more against the terrible Lone Power on an unusual battleground, as they fight for the heart and mind of a young wizard with the power to save their world…

Initially, Kit finds himself flying solo as Nita has sunk into a deep depression after the events of The Wizard's Dilemma. Luckily, Kit's telepathic pooch, Ponch, is happy to fill Nita's niche temporarily, as long as enough dog biscuits are involved.

Kit's fighting to understand why autistic wizard-in-training Darryl McAllister has been stuck in his wizardly Ordeal for over three months. Is it merely the fault of his autism? Exploring inside Darryl's mind, Kit and Ponch discover complex landscapes of weird beauty that belie Darryl's rocking, vacant exterior. But they also find the Lone Power, attacking Darryl with a relentless brutality that seems to make little sense. What makes Darryl so important — and why can't he escape his Ordeal?

Nita, meanwhile, is distracted from her sorrow by a series of strange dreams in which some mysterious being pleads desperately for her aid. What do the cryptic messages mean? She has to find out quickly — because now Kit, too, has vanished. Can she find him — and if she does, will the two of them be able to come together in time to deal with the Lone Power before It can destroy them?

A Wizard Alone

by Diane Duane

Life more than just being alive (and worth the pain) but hurts: fix it grows: keep it growing wants to stop: remind check I don’t hurt be sure!

One’s watching: get it right!

later it all works out, honest meantime, make it work now (because now is all you ever get: now is)

— The Wizard’s Oath, excerpt from a private recension

Footsteps in the snow suggest where you have been, point where you were going: but where they suddenly vanish, never dismiss the possibility of flight___

— Book of Night with Moon, XI, V.

Consultations

In a living room of a suburban house on Long Island, a wizard sat with a TV remote control in his hand, and an annoyed expression on his face. “Come on,” he said to the remote. “Don’t give me grief.”

The TV showed him a blue screen and nothing more.

Kit Rodriguez sighed. “All right,” he said, “we’re on the record now. You made me do this.” He reached for his wizard’s manual on the sofa next to him, paged through it to its hardware section — which had been getting thicker by the minute this afternoon — found one page in particular, and keyed into the remote a series of characters that the designers of both the remote and the TV would have found unusual.

The screen stayed mostly blue, but the nature of the white characters on it changed. Until now they had been words in the Roman alphabet. Now they changed to characters in a graceful and curly cursive, the written form of the wizardly Speech. At the top of the screen they showed the local time and the date expressed as a Julian day, that being the Earth-based system most closely akin to what the manual’s managers used to express time. In the middle of the blue screen appeared a single word:

WON’T.

Kit let out a long breath of exasperation. “Oh, come on,” he said in the Speech. “Why not?”

The screen remained blue, staring at him mulishly. Kit wondered what he’d done to deserve this.

“It can’t be that bad,” he said. “You two even have the same version number.”

VERSIONS AREN’T EVERYTHING!

Kit rubbed his eyes.

“I thought a six-year-old child was supposed to be able to program one of these things,” said a voice from the next room.

“I sure feel like a six-year-old at the moment,” Kit muttered. “It would work out about the same.”

Kit’s father wandered in and stood there staring at the TV. Not being a wizard himself, he couldn’t see the Speech written there, and wouldn’t have been able to make sense of it if he had, but he could see the blue screen well enough. “So what’s the problem?”

“It looks like they hate each other,” Kit said.

His father made a rueful face. “Software issues,” he said. He was a pressman for one of the bigger news-papers on the Island, and in the process of the company converting from hot lead to electronic and laser printing, he had learned more than most people cared to know about the problems of converting from truly hard “hardware” to the computer kind.

“Nope,” Kit said. “I wish it were that simple.”

“What is it, then?”

Kit shook his head. Once upon a time, not so long ago, getting mechanical things to see things his way had been Kit’s daily stock-in-trade. Now everything seemed to be getting more complex by the day. “Issues they’ve got, all right,” he said. “I’m not sure they make sense to me yet.”

His father squeezed his shoulder. “Give it time, son,” he said. “You’re a brujo; nothing can withstand your power.”

“Nothing that’s not made of silicon, anyway,” Kit said.

His father rolled his eyes. “Tell me all about it,” he said, and went away.

Kit sat there staring at the blue screen, trying to sort through the different strategies he’d tried so far, determining which ones hadn’t worked, which ones had worked a little bit, and which ones had seemed to be working just fine until without warning they crashed and burned. The manual for the new remote said that the new DVD player was supposed to look for channels on the TV once they were plugged into each other, but the remote and the DVD player didn’t even want to acknowledge each other’s existence so far, let alone exchange information. Neither the DVD’s manual nor the remote’s was any help. The two pieces of equipment both came from the same company, they were both made in the same year and, as far as Kit could tell, in the same place. But when he listened to them with a wizard’s ear, he heard them singing two different songs — in ferocious rivalry — and making rude noises at each other during the pauses, when they thought no one was listening.

“Come on, you guys,” he said in the Speech. “All I’m asking for here is a little cooperation—”

“No surrender!” shouted the remote.

“Death before dishonor!” shouted the DVD player.

Kit covered his eyes and let out a long, frustrated breath.

From the kitchen came a sudden silence, something that was as arresting to Kit as a sudden noise, and that made him look up in alarm. His mother had been cooking. Indeed, she was making her arroz con polio, a dinner that visiting heads of state would consider themselves lucky to eat.

When without warning it got quiet in the kitchen in the middle of that process, Kit reacted as he would have if he’d heard someone say, “Oops!” during the countdown toward a space shuttle launch: with held breath and intense attention.

“Honey?” Kit’s mom said.

“What, Mama?”

“The dog says he wants to know what’s the meaning of life.”

Kit rubbed his forehead, finding himself tempted to hide his eyes. “Give him a dog biscuit and tell him it’s an allegory,” Kit said.

“What, life?”

“No, the biscuit!”

“Oh, good. You had me worried there for a moment.”

Kit’s mother’s sense of humor tended toward the dry, and the dryness sounded like it was set at about medium at the moment, which was just as well. His mother was still in the process of getting used to his wizardry. Kit went back to trying to talk sense into the remote and the DVD player. The

DVD player blued the TV’s screen out again, pointedly turning its attention elsewhere.

“Come on, just give each other a chance.”

“Talk to that thing? You must have a chip l

oose.”

“Like I would listen!”

“Hah! You’re a tool, nothing but a tool! I entertain!”

“Oh yeah? Let’s see how well you entertain when I turn you off like a light!”

Kit rolled his eyes. “Listen to me, you two! You can’t get hung up on the active-role-passive-role thing. They’re both just fine, and there’s more to life—”

“Like what?!”

Kit’s mama came drifting in and looked over Kit’s shoulder as he continued to speak passionately to the remote and the DVD player about the importance of cooperation and teamwork, the need not to feel diminished by acting, however briefly, as part of a whole. But the remote refused to do anything further, and the screen stayed blue. Kit started to think he must be turning that color in the face.

“It sounds like escargot,” his mother said, leaning her short, round self over him to look at the

TV.

“What?”

“Sorry. Esperanto. I don’t know why the word for snails always comes out first.”

Kit looked at his mother with some interest. “You can hear it?” he said. It was moderately unusual for nonwizards to hear the Speech at all. When they did, they tended to hear it as the language they spoke themselves — but because the Speech contained and informed all languages, being the seed from which they grew, this was to be expected.

“I hear it a little,” his mother said. “Like someone talking in the next room. Which it was…”

“I wonder if the wizardry comes from your side of the family,” Kit said.

His mother’s broad and pretty face suddenly acquired a nervous quality. “Uh-oh, the chicken broth,” she said, and took herself back to the kitchen.

“What about Ponch?” Kit said.

“He ate the dog biscuit,” his mother said after a moment.

“And he didn’t ask you any more philosophical stuff?”

“He went out. I think he had a date with a biological function.”

Kit smirked, though he turned his face so she wouldn’t see it if she came back in. His mother’s work as a nurse expressed itself at home in two ways: either detailed and concrete descriptions of things you’d never thought about before and (afterward) desperately never wanted to think about again, or shy evasions regarding very basic physical operations that you’d think wouldn’t upset a six-year-old. Ponch’s business seemed mostly to elicit the second response in Kit’s mama, an effect that usually made Kit laugh.

At the moment he just felt too tired. Kit paused in his cheerleading and went rummaging through the paperwork on the floor for the DVD’s and remote’s manuals. We’re in trouble when even a remote control has its own manual, he thought. But if a wizard with a bent toward mechanical things couldn’t get this kind of very basic problem sorted out, then there really would be trouble.

He spent a few moments with the manuals, ignoring the catcalls and jeers that the recalcitrant pieces of equipment were trading. Then abruptly Kit realized, listening, that the DVD did have a slightly different accent than the remote and the TV. Now, I wonder, he thought, and went carefully through the DVD’s manual to see whether the manufacturer actually had made all the main parts itself.

The manual said nothing about this, being written in a broken English that assumed the system was, indeed, being assembled by the proverbial six-year-old. Resigned, Kit picked up the remote again, which immediately began shouting abuse at him. At first he was relieved that this was inaudible to everybody else, but the DVD chose that moment to take control of the entertainment system’s speakers and start shouting back.

“Oooh, what a nasty mouth,” said his sister Carmela as she walked through the living room, wearing her usual uniform of floppy jeans and huge floppy T-shirt, and holding a wireless phone in her hand. She had been studying Japanese for some months, mostly via watching anime, and had now graduated to an actual language course — though what she chiefly seemed interested in were what their father wryly called “the scurrilities.” “Bakka aho kikai, bakka-bakka!”

Kit was inclined to agree. He spent an annoying couple of moments searching for the volume control on the DVD — the remote was too busy doing its own shouting to be of any use. Finally he got the DVD to shut up, then once again punched a series of characters into the remote to get a look at the details on the DVD’s core processor.

“Aha,” Kit said to himself. The processor wasn’t made by the company that owned the brand. He had a look at the same information for the remote. It also used the same processor, but it had been resold to the brand-name company by still another company.

“Now look at that!” Kit said. “You have the same processors. You aren’t really from different companies at all. You’re long-lost brothers. Isn’t that nice? And look at you, fighting over nothing!

She’s right, you are idiots. Now I want you guys to handshake and make up.”

There was first a shocked silence, then some muttering and grumbling about unbearable insults and who owed whom an apology. “You both do,” Kit said. “You were very disrespectful to each other. Now get on with it, and then settle down to work. You’ll have a great time. The new cable package has all these great channels.”

Reluctantly, they did it. About ten minutes later the DVD began sorting through and classifying the channels it found on the TV. “Thank you, guys,” Kit said, taking a few moments to tidy up the paperwork scattered all over the floor, while thinking longingly of the oncoming generation of wireless electronics that would all communicate seamlessly and effortlessly with one another. “See, that wasn’t so bad. But someday all this will be so much simpler,” Kit said, patting the top of the DVD player.

“No, it won’t,” the remote control said darkly.

Kit rolled his eyes and decided to let the distant unborn future of electronics fend for itself. “You just behave,” he said to the remote, “or you’re gonna wind up in the Cuisinart.”

He walked out of the living room, ignoring the indignant shrieks of wounded ego from the remote. This had been only the latest episode in a series of almost constant excitements lately, which had begun when his dad broke down after years of resistance and decided to get a full-size entertainment center. It was going to be wonderful when everything was installed and everything worked. But in the meantime, Kit had become resigned to having a lot of learning experiences.

From the back door at the far side of the kitchen came a scratching noise: his dog letting the world know he wanted to come back in. The scratching stopped as the door opened. Kit turned to his pop, who had just come into the dining room again, and handed him the remote. “I think it’s fixed now,” he said. “Just do this from now on: Instead of using this button to bring the system up, the one the manual tells you to, press this, and then this.” He showed his pop how to do it.

“Okay. But why?”

“They may not remember the little talking-to I just gave them — it depends on how the system resets when you turn it off. This should remind them…I hardwired it in.”

“What was the problem?”

“Something cultural.”

“Between the remote and the DVD player?! But they’re both Japanese.”

“Looks like it’s more complicated than that.” There seemed to be no point in suggesting to his pop that the universal remote and the DVD were both unsatisfied with their active or passive modes.

Apparently doing what you had been built to do was a prospect no more popular among machines than it was among living things. Everything had its own ideas about what it really should be doing in the world, and the more memory you installed in the hardware, the more ideas it seemed to get.

Kit realized how thirsty all this talking to machinery had made him. He went to the fridge and rummaged around to see if there was some of his mom’s iced tea in there. There wasn’t, only a can of the lemon soft drink that Nita particularly liked and that his mom kept for her.

The sight of it made Kit briefly uncomfortable. But neither wizardry

nor friendship was exclusively about comfort. He took the lemon fizz out, popped the can’s top, and took a long swig.

Neets

? he said silently.

Yeah

, she said in his mind.

There wasn’t much enthusiasm there, but there hadn’t been much enthusiasm in her about anything for some weeks. At least it wasn’t as bad for her now as it had been right after her mother’s funeral. But clearly Kit wondered whether the bitter pain she’d been in then was, in its way, healthier than her current gray, dull tone of mind, like an overcast that showed no signs of lifting.

Then he immediately felt guilty for even being tempted to play psychiatrist. She had a right to grieve at whatever speed was right for her.

Busy today?

Not really.

Kit waited. Normally Nita would now come forth with at least some explanation of what “not really” involved. But she wasn’t anything like normal right now, and no explanation came — just that sense of weariness, the same tired why-bother feeling that kept rearing up at the back of Kit’s mind.

Whether he was catching it directly from her via their private channels of communication, or whether it was something of his own, he wasn’t sure. It wasn’t as if he didn’t miss Nita’s mother, too.

I finished fixing the TV, Kit said, determined to keep the conversation going, no matter how uncomfortable it made him. Someone around here had to try to keep at least the appearance of normalcy going. Now I’m bored again… and I want to stay that way for a while. Wanna go to the moon?

There was a pause. No, Nita said. Thanks. I just don’t feel up to it today. And there it was, the sudden hot feeling of eyes filling with tears, without warning; and Nita frowning, clenching her eyes shut, rather helplessly, unable to stop it, determined to stop it. You go ahead. Thanks, though.

She turned away in thought, breaking off the silent communication between them. Kit found that he, too, was scowling against the pain, and he let out a long breath of aggravation at his own helplessness. Why is it so embarrassing to be sad? he thought, annoyed. And not just for me. Nita’s overwhelming pain embarrassed her as badly as it did him, so Kit had to be careful not to “notice” it.

The Book of Night With Moon

The Book of Night With Moon A Wind From the South

A Wind From the South A Wizard Abroad, New Millennium Edition

A Wizard Abroad, New Millennium Edition Lior and the Sea

Lior and the Sea Uptown Local and Other Interventions

Uptown Local and Other Interventions High Wizardry New Millennium Edition

High Wizardry New Millennium Edition Games Wizards Play

Games Wizards Play Wizard's Holiday, New Millennium Edition

Wizard's Holiday, New Millennium Edition So You Want to Be a Wizard, New Millennium Edition

So You Want to Be a Wizard, New Millennium Edition The Door Into Sunset

The Door Into Sunset To Visit the Queen

To Visit the Queen A Wizard Abroad

A Wizard Abroad Not on My Patch

Not on My Patch The Door Into Shadow

The Door Into Shadow The Door Into Fire

The Door Into Fire A Wizard Alone New Millennium Edition

A Wizard Alone New Millennium Edition The Tale of the Five Omnibus

The Tale of the Five Omnibus The Wizard's Dilemma, New Millennium Edition

The Wizard's Dilemma, New Millennium Edition The Big Meow

The Big Meow Wizards at War, New Millennium Edition

Wizards at War, New Millennium Edition Interim Errantry

Interim Errantry Omnitopia: Dawn

Omnitopia: Dawn High Wizardry

High Wizardry Spider-Man: The Venom Factor Omnibus

Spider-Man: The Venom Factor Omnibus Spider-Man: The Venom Factor

Spider-Man: The Venom Factor Seaquest DSV

Seaquest DSV How Lovely Are Thy Branches

How Lovely Are Thy Branches So You Want to Be a Wizard

So You Want to Be a Wizard Midnight Snack and Other Fairy Tales

Midnight Snack and Other Fairy Tales Stealing the Elf-King's Roses

Stealing the Elf-King's Roses Interim Errantry 2: On Ordeal

Interim Errantry 2: On Ordeal Raetian Tales 1: A Wind from the South

Raetian Tales 1: A Wind from the South Starrise at Corrivale h-1

Starrise at Corrivale h-1 The Wizard's Dilemma

The Wizard's Dilemma Sand and Stars

Sand and Stars How Lovely Are Thy Branches: A Young Wizards Christmas

How Lovely Are Thy Branches: A Young Wizards Christmas On Her Majesty's Wizardly Service fw-2

On Her Majesty's Wizardly Service fw-2 X-COM: UFO Defense

X-COM: UFO Defense Star Trek: The Original Series: Rihannsu, Book 5: The Empty Chair

Star Trek: The Original Series: Rihannsu, Book 5: The Empty Chair seaQuest DSV: The Novel

seaQuest DSV: The Novel Stealing the Elf-King's Roses: The Author's Cut

Stealing the Elf-King's Roses: The Author's Cut Not On My Patch: a Young Wizards Hallowe'en Story

Not On My Patch: a Young Wizards Hallowe'en Story A Wizard Alone yw[n&k-6

A Wizard Alone yw[n&k-6 The Bloodwing Voyages

The Bloodwing Voyages Games Wizards Play (Young Wizards Series)

Games Wizards Play (Young Wizards Series) The Book of Night with Moon fw-1

The Book of Night with Moon fw-1 My Enemy My Ally

My Enemy My Ally Dark Mirror

Dark Mirror Star Trek: The Original series: Rihannsu: The Bloodwing Voyages

Star Trek: The Original series: Rihannsu: The Bloodwing Voyages Deep Wizardry yw[n&k-2

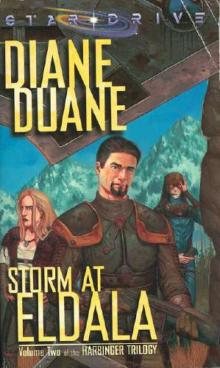

Deep Wizardry yw[n&k-2 Storm at Eldala h-2

Storm at Eldala h-2