- Home

- Diane Duane

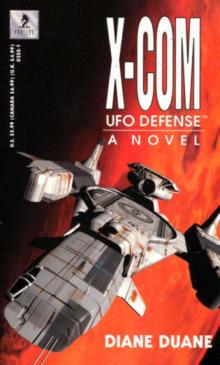

X-COM: UFO Defense Page 7

X-COM: UFO Defense Read online

Page 7

Ari looked thoughtful at that. “I thought there had been a worldwide drop-off in cattle abductions.” He did not add, possibly because the rate of human abductions seems to have gone up so sharply in the last few months. That wasn’t public knowledge, and X-COM was hoping that the world’s governments were too busy at the moment to compare figures. The data raised some uncomfortable questions, such as whether the aliens had finished getting whatever data they needed from cows and other higher non-primate animals, and were now concentrating on the primates.

“Well,” Jonelle said, “I thought so too. But now it seems like something else is going on, and I don’t know what it means. In any case, I don’t like it. I’m going to get onto the data-processing people at the bases at Omaha and Tsingtao, and see what they can tell me. Whether this is just a statistical blip, or something else.”

Ari frowned. “There weren’t many cattle mutilations in Morocco. Then again, there weren’t that many cattle in Morocco.”

“There are enough.” Jonelle leaned back. “But those cows never struck me as anything special. These cows…I don’t know. In any case, the locals are very attached to them, and it wouldn’t hurt our PR effort here if we, as a ‘UN organization,’ can get someone, in some unspecified way, to do something to help protect their cows while also taking care of other business. You get my drift, Colonel?”

Ari looked at her. “If you mean you’re going to be sending me back to Morocco tonight or tomorrow,” he said, “that drift I get.”

Now how did he…. Jonelle sat up straighten

“You’re not going to need me here much longer,” Ari said. “I’ve talked to the construction crews all I need to— their liaison with the army is in place now. The army people, all but the highest, think our people are going to be building some kind of new installation for the Swiss— so that’s settled. The basic installation schedule is just about set up. Temporary living quarters will be ready within a couple-few days, the rest within a week or so. After that we start bringing in the basic heavy stuff— that’ll take another week. All those production and delivery schedules are tight, and confirmed by the supply depots in the US and China. We’re lucky, this place is a natural hangar. The number-one level hangar space is almost all ready but for the doors—they’re working on that. Two, three more days—four, max. After that comes conversion of the second level for hangar space, which is in a similar state, but will take more time. The concealed entrance is going to have to be widened, while under cover, to take our bigger craft. Two weeks worth at least.”

“What about the conversion of the containment spaces?”

Ari looked self-satisfied. “My cubbyholes will be ready by the end of the week. They’re no use to you, though, without the environmental controls and the proper security in place, and the base won’t be ready for them until the third week or so. Sorry, Boss.”

Jonelle breathed out and leaned back again, looking at him steadily. Outside, on the street, dusk was beginning to fall, along with the first few flakes of a snow that had been threatening all day. “We have a problem,” she said.

“Local? Or back in Morocco?”

“Morocco,” she said. “Business is starting to pick up again down that way.”

“How many interceptions last night?”

“Six,” she said.

“How did they do?”

Jonelle shook her head. “Not at all as well as they should have.” This was an understatement, but she was determined not to contaminate Ari’s assessment of the situation with her opinions, forceful though they might be. DeLonghi, she thought, is looking like the worst idea I’ve had in a month of Sundays…but it might he that he’s shaken by the sudden promotion and needs a little help to steady down. I intend to see that he gets it. “Commander DeLonghi’s team assignments seem to have been most at fault. I want you to get down there tonight and take up a consultative role.”

“And I’ll be flying missions, too, of course.”

Jonelle paused. This was where she should have said, easily Of course. But she couldn’t get out of her mind Ari’s last mission. That one had been very close. His impulsiveness…. Yet the last thing a responsible commander in her position should do was try to shield one of her people from the correct exercise of their duties, for strictly personal reasons.

“Of course,” she said. “One thing: I require you not to expose yourself to what I would consider unnecessary danger while you’re in consultative mode. When you’re supervising a number of teams, which you may be for the next little while, you stay out of the front line.”

She watched Ari contemplating the wording of her order to see if there was some way he could squirm out of it. But Jonelle had been thinking about this for some hours. “I would do this myself if I had the leisure,” she said, “but I don’t. Though I can turn this office over to our PR people full-time tomorrow, there are other matters connected with getting this base running besides strictly construction-oriented ones, and I’ve got to deal with them.” That mind shield, she thought, still wondering where the heck she was going to find the necessary cash for it. A shield was so necessary, up here where there were so many more people living nearby than there were in Morocco.

“Yes, ma’am,” Ari said.

“Is that a wilco?” said Jonelle.

Ari looked at her for a moment, then said, “Wilco.”

“Thank you,” Jonelle said—something she did not have to say, and Ari knew it. “I’d be glad if you were on your way down there as quickly as possible. I can’t get out of my head the idea that the aliens may have some intelligence about what we’re doing…and I would very much dislike seeing our work here interrupted because of ineptly constructed and dispatched interceptions. I want my best pilot on site to advise the new commander at Irhil.”

He looked at her with a flattery-will-get-you-nowhere sort of expression, but an affectionate and respectful one. “I’ll be back there in a couple of hours,” Ari said. “There’s a transport leaving the mountain in fifty minutes—I’ll be on it.”

“Very well. Is there anything else construction-oriented I need to know about?”

“No, Commander.”

“All right. Let me give you the details about last night’s interceptions. You’ll want to look at the transcripts yourself when you get back, but I think you’ll find some patterns.”

They spent half an hour going over the fine points of whose team had been misassigned, who needed to be spoken to about weapons allocations and armor, who was carrying weapons too light or too heavy for their best use. Outside, the snow began falling more thickly, blowing golden-colored in the light of the streetlight by the door.

When they were finished, Ari saluted Jonelle and said, “Good night, Commander.”

Jonelle saw a great deal in his eyes that he was not going to express, even here when they were alone. Concern for her—and a great eager desire to get back to the things he loved best: flying his Firestorm and leading ground assaults. “Good night, Colonel,” she said, returning the salute, “and good hunting. I’ll expect a report first thing in the morning on improvement of the teams’ results.”

“You’ll have it.” And out he went into the snow, stopping once to look up and down the street—not for traffic, Jonelle saw, but to tell whether he was likely to step in anything bovine and unexpected.

She smiled and turned back to the desk with a resigned look, thinking about that mind shield again, and eyeing the piled-up filing.

Many miles north, in Zürich, dusk was also falling, though not snow. It was rush hour, and the rain had been coming down gently for about an hour now, drifting from one of those low-ceilinged overcasts in which the city seems to specialize in the fall. From the stone front steps of the Hauptbahnhof—the main train station—the view up the long, wide Bahnhofstrasse—the main street downtown, known for its shopping—was much shortened by the misting rain. A few blocks up, the street disappeared in swathes of silver-gray only the stores’ illuminated signs

and windows blooming through the wet, drifting fog. Mist was tangled in the upper branches of even the youngest of the lime trees lining the street. The logos of the big banks facing into Paradeplatz three blocks down were mere ghosts of themselves, phantom aspirin-tablets or crossed keys glowing through the gray. Far below them, the blue and white Zurich city trams glided and hummed along the Bahnhofstrasse tracks, single headlights glowing brighter through the gloom and double taillights vanishing as they went. On either side, bundled-up people hurried along the gray and white sidewalks, heading for the tram stops or the escalators at the corner of the Strasse and Bahnhofplatz, which led down and over into the train station.

The high whine that started to become audible made some of the passersby look up, and some who were closer to the Hauptbahnhof looked back toward the train station, though dubiously. Sometimes one heard the occasional screech of wheels from the train yards, but it wouldn’t be so prolonged a sound. Others glanced up the road to see if a tram was coming that possibly had an engine fault. But the trams were making no louder a hum than usual. Maybe it was just the fog. It could seem to concentrate the sound, sometimes.

But no fog could make anything—tram, train, or jet— sound like this. The whine scaled up into a scream, and the scream got louder and louder.

That was when the shape came slowly, gently bellying down out of the mist over the Zürich train station. It looked like two very large octagons stacked on top of each other, with four octagonal pods underneath. Slowly and with seeming care, it sat itself down on the stately neo-Baroque upper hall of the station—and down, and farther down, until huge blocks of stone burst out of the structure under the pressure and flew across the plaza, smashing into the hotels there and rendering some of the guests’ stays unexpectedly permanent. Other fragments shot into the fairy-tale towers of the Swiss National Museum behind the Bahnhof, knocking the greened-bronze conical tops off them and leaving them like stumps of broken teeth.

At the same time, a Terror Ship settled down out of the fog onto Paradeplatz, crushing a tram underneath it. The driver of a second tram, turning the curve out of the plaza and heading north toward the Bahnhof, saw what had happened to that building and decided it might be wiser not to continue his run much farther. He stopped the tram, opened all its doors, and held his post while his passengers fled. Then he powered the tram down, checked it to make sure no one had been left behind, and jumped out himself, turning by the front door to put in the key that would let him shut the doors and lock the tram from the outside. It was the last thing he ever did as a human being. A. second later, a Chryssalid’s venom was blasting through his body, and the tram key fell ringing gently onto the cobbles, unnoticed.

The screams in Paradeplatz, as Floaters and Reapers poured out of the Terror Ship and descended on the terrified crowds of commuters, were echoed from the Hauptbahnhof. Not even the bulk of a Battleship was able to completely crush the iron skeleton of the great railway station, Jakob Wanner’s masterpiece; but destruction of mere landmarks was secondary to the aliens’ purposes.

Snakemen and Chryssalids poured out of the Battleship and made their way down the stations three levels underneath the old main building. Sirens were beginning to howl outside, the police beginning to respond, but the shrieks and cries of those in the station—both those maimed or dying under its wreckage and those being torn apart or taken alive by aliens—were louder still. On the street level, at the end of the Bahnhofstrasse, people ran desperately in all directions, looking for somewhere to hide, but there was nowhere. Stores locked their doors, but Snakemen crashed in through plate glass windows to find their prey. Cyberdiscs blasted their way through hastily dropped security shutters and racketed around inside the breached premises like psychotic Frisbees, killing everything that moved, shooting everything that didn’t. Plasma-weapon fire began in earnest out on the streets, and stun bombs and grenades could be heard everywhere. Unconscious and wounded humans were carried into the waiting ships to be experimented on later. Others, more fortunate, died quickly, burned or blasted or torn apart. The gray and white pavements began to acquire a new color: red.

And in the Bahnhof, that temple to punctuality, the trains stopped running on time.

A few hours after he left Jonelle, as he had predicted, Ari landed at Irhil—and he could hear the buzz from the hangars before he ever got near them. People were running in all directions, some with pleased expressions, others with looks that suggested they felt more like the denizens of a kicked anthill.

The last thing he wanted to do was head away from the hangars, but he did that regardless, making his way to the commanders office as quickly as he could. It was very strange to knock on that door and not hear the familiar “Ngggh?” which was Jonelle’s standard response. DeLonghi’s voice said, “Come!” from inside, and Ari was astounded to feel a pang at it not being Jonelle. No time for this, he thought.

He walked in to find DeLonghi sitting in the middle of a desk piled high with reports and God only knew what else. The sheer weight of stuff, on a desk that he had only seen clean before, made Ari pause in amazement.

“You wanted something, I take it?” DeLonghi said, looking up and frowning. “I’m rather busy at the moment.”

Ari saluted and said, “Sorry, sir. The commander—”

“Yes, I know, sit down and let’s get on with it,” DeLonghi growled. Ari sat down, not feeling entirely comfortable. DeLonghi had never been the easiest man to get along with. There was not precisely bad blood between them, but DeLonghi had never been that accomplished a fighter, or pilot, or strategist. There was a feeling in ranks that he was one of those who had accomplished his climb strictly “by the numbers,” because he couldn’t have managed it any other way. Ari suspected that DeLonghi knew perfectly well about this opinion of his peers, and that it rankled him. Privately, Ari—regarded on the base as one of their best pilots—wished that Jonelle had stuck him with almost any other job than that of having to advise this man, who would almost certainly take any advice as something meant to make him look dumb.

“What’s the situation at the moment?”

“Thought you would have checked on the way up,” DeLonghi said irritably.

“I did, sir,” Ari said, “but much may have changed since then.” He glanced at the ceiling, as if calculating, and said, “One Interceptor is in Kenya, having splashed an alien Scout Craft. Two dead, equipment and resource recovery uncertain. It appears to have been a feint. The other Interceptor is in the Péloponnčse, scrambled just after the first one. Chased a medium Scout into the water between islands. One dead, and the Interceptor is on its way back here, having suffered damage. This too may have been a feint of some kind. Our Skyranger is en route to an alien landing site in the Canary Islands. The first ship we sent in, a Lightning, has been destroyed with loss of all crew. It was carrying a full load of twelve soldiers.” Who do I know who is ashes or a corpse in the Atlantic right now? Ari thought. “Another Lightning is en route to a landing site near the old diggings at Çatal Huyuk in Turkey. ETA ten minutes. The third Lightning is in Burkina Faso, cleaning up an alien terror site. Heavy casualties: the captain on site reports two-thirds of his assault team dead, along with fifty-odd civilians. The fourth Lightning is still finishing maintenance, should be ready tonight. Two of three Firestorms are out, one on an interception over the Mediterranean, heading toward Egypt when last reported. The other is heading up the French coast toward Brittany, in pursuit, reporting that the alien craft, a Harvester, seemed to be making toward Great Britain but has now doubled back and may be bound for Paris or the Benelux region instead. As of my last check, anyway.”

Ari watched DeLonghi go increasingly red, and he could understand why: his information was no more than three minutes’ old—possibly fresher than the commander’s own.

There was no question, apparently, that the commander knew this. “Colonel,” DeLonghi said, “I hear the sound of a man looking to catch me in a mistake. Are you bucking for my job?”<

br />

Ari blinked. He had realized on the way there that Jonelle had sent him to Morocco in the hopes of forestalling this situation, but the aliens had had other plans. “Sir,” Ari said, “if you think—”

“Because don’t think that I don’t know, as does everyone else here, the nature of your relationship with the regional commander. And if you think that her position will protect you when you make your move, then you’ve—”

“Commander,” Ari said, “permission to speak as freely as you have already begun to.”

DeLonghi blinked—a dreadful expression, like a cobra blinking while it had a slow, cold thought—and then said, “Granted.”

Ari sat back in his chair and said, “Sir. Your materiel is spread dangerously thin. You have scattered a large force, which would otherwise have been in a position to lend itself assistance, as it were, internally, over two continents.” DeLonghi’s face was a study: whatever he had been expecting Ari to say, it wasn’t this calm assessment. “I understand the cause of this, and indeed you had no choice. You reacted to each crisis, and logically, as it arose. But these crises show signs of having been designed to do precisely what you have—spread us out. Someone knows from experience what resources we have here. Someone may also know that there has been, shall we say, a change in management. Whether they knew before, or not, the actions of the past few hours have convinced them. Now, you find yourself with few resources left to deal with any large incursion. I would expect such an incursion to happen any minute. I’ve seen this happen before, when the regional commander first took over here, and the pattern—”

The klanger went off somewhere down the hall, and after it the pilots-to-hangar shouter, a melancholy hooting like an elephant sorry it ate that last tree. At the same time, the commander’s phone went off. He snatched up the handset and almost yelled, “What?”

The Book of Night With Moon

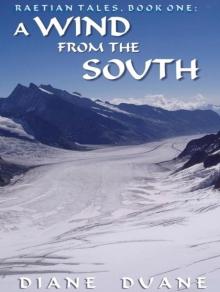

The Book of Night With Moon A Wind From the South

A Wind From the South A Wizard Abroad, New Millennium Edition

A Wizard Abroad, New Millennium Edition Lior and the Sea

Lior and the Sea Uptown Local and Other Interventions

Uptown Local and Other Interventions High Wizardry New Millennium Edition

High Wizardry New Millennium Edition Games Wizards Play

Games Wizards Play Wizard's Holiday, New Millennium Edition

Wizard's Holiday, New Millennium Edition So You Want to Be a Wizard, New Millennium Edition

So You Want to Be a Wizard, New Millennium Edition The Door Into Sunset

The Door Into Sunset To Visit the Queen

To Visit the Queen A Wizard Abroad

A Wizard Abroad Not on My Patch

Not on My Patch The Door Into Shadow

The Door Into Shadow The Door Into Fire

The Door Into Fire A Wizard Alone New Millennium Edition

A Wizard Alone New Millennium Edition The Tale of the Five Omnibus

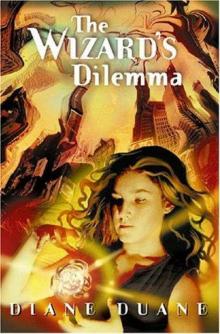

The Tale of the Five Omnibus The Wizard's Dilemma, New Millennium Edition

The Wizard's Dilemma, New Millennium Edition The Big Meow

The Big Meow Wizards at War, New Millennium Edition

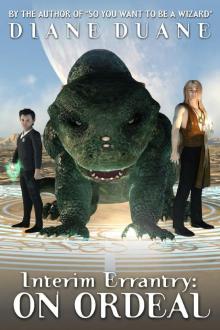

Wizards at War, New Millennium Edition Interim Errantry

Interim Errantry Omnitopia: Dawn

Omnitopia: Dawn High Wizardry

High Wizardry Spider-Man: The Venom Factor Omnibus

Spider-Man: The Venom Factor Omnibus Spider-Man: The Venom Factor

Spider-Man: The Venom Factor Seaquest DSV

Seaquest DSV How Lovely Are Thy Branches

How Lovely Are Thy Branches So You Want to Be a Wizard

So You Want to Be a Wizard Midnight Snack and Other Fairy Tales

Midnight Snack and Other Fairy Tales Stealing the Elf-King's Roses

Stealing the Elf-King's Roses Interim Errantry 2: On Ordeal

Interim Errantry 2: On Ordeal Raetian Tales 1: A Wind from the South

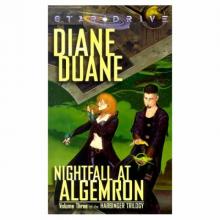

Raetian Tales 1: A Wind from the South Starrise at Corrivale h-1

Starrise at Corrivale h-1 The Wizard's Dilemma

The Wizard's Dilemma Sand and Stars

Sand and Stars How Lovely Are Thy Branches: A Young Wizards Christmas

How Lovely Are Thy Branches: A Young Wizards Christmas On Her Majesty's Wizardly Service fw-2

On Her Majesty's Wizardly Service fw-2 X-COM: UFO Defense

X-COM: UFO Defense Star Trek: The Original Series: Rihannsu, Book 5: The Empty Chair

Star Trek: The Original Series: Rihannsu, Book 5: The Empty Chair seaQuest DSV: The Novel

seaQuest DSV: The Novel Stealing the Elf-King's Roses: The Author's Cut

Stealing the Elf-King's Roses: The Author's Cut Not On My Patch: a Young Wizards Hallowe'en Story

Not On My Patch: a Young Wizards Hallowe'en Story A Wizard Alone yw[n&k-6

A Wizard Alone yw[n&k-6 The Bloodwing Voyages

The Bloodwing Voyages Games Wizards Play (Young Wizards Series)

Games Wizards Play (Young Wizards Series) The Book of Night with Moon fw-1

The Book of Night with Moon fw-1 My Enemy My Ally

My Enemy My Ally Dark Mirror

Dark Mirror Star Trek: The Original series: Rihannsu: The Bloodwing Voyages

Star Trek: The Original series: Rihannsu: The Bloodwing Voyages Deep Wizardry yw[n&k-2

Deep Wizardry yw[n&k-2 Storm at Eldala h-2

Storm at Eldala h-2