- Home

- Diane Duane

The Door Into Sunset Page 5

The Door Into Sunset Read online

Page 5

“Not likely.”

“Dritt....”

“‘But should you refuse this alternative, then Fórlennh and Hergótha Our swords are turned irrevocably against you, and red war is yours until you die. Consider well your choice; and the Goddess guide it for Arlen’s sake, and yours. An end to Our words. —For to ensure that these letters fall not into the hands of those who mean Our lands no good, we have entrusted them to the hand of Our loyal friend and subject lord Herewiss stareiln Hearn stai-Eálorsti kyn’Éarnësti, Prince-elect of the Brightwood and a lord-member of the Comraderie of the WhiteCloak. These letters given under My hand in Sai Urdárien, that is Blackcastle, in My city of Darthis, this first day of Summer in the second year of My reign, being the two thousand nine hundred twenty-seventh year after the coming of the Dragons. Eftgan as’t’Raïd Darthéni.’“

“Dear Goddess,” Eftgan said.

“What? Did I spell as’t’Raïd wrong again?”

“No, no....” Eftgan leaned back in her tall carved chair and stared at Herewiss—a wry look. “Hark to you! What makes you think I can spare you for a vacation in Arlen?”

“Who else could you send,” Herewiss said, “that you could count on to get there, and stay there, without being murdered?”

“Me,” Segnbora said, from down the table.

“Be still a moment,” Freelorn said. “I didn’t forget you. Eftgan, it’s perfect.”

“You put him up to this, did you? Later for you, Lion’s whelp. And what makes either of you think I want to go to battle so soon? I was thinking of next spring—”

Freelorn reached out to the parchment and glanced down over it at the slightly tilted vertical lines of Herewiss’s fat neat cursive. “Queen, why throw away a perfectly good famine? Springtime—when people will have barely survived a long bad winter—isn’t as good a time to get them to fight as the fall, when the winter’s before them and looking horrible. Besides, this business needs to be settled before the spring planting. Maybe you have better news of Darthen, but from what I’ve seen of Arlen in the past year, it can’t bear another year of drought. We need this winter’s snow.” He began curling and uncurling a corner of the parchment. “Otherwise you know what’s coming as well as I do, if you think of it. In a year, maybe two, rule in Arlen collapses, and the refugees spill over into Darthen, in desperation, to keep from starving. The Reavers come over the invasion routes that haven’t yet been closed, and can no longer be held, and over a few seasons wipe out the few who’ve managed to survive that long. In the end... nothing. Waste land; the Shadow will kill off even the Reavers when they’ve served Its purpose and exterminated us.” He smiled, an unhappy look. “And then who’s left to help the Goddess run the world?”

Eftgan chewed her lip. “Fall it is, then. But my forces are scattered right now, and diminished in numbers after Bluepeak.”

Freelorn shrugged. “I don’t see how we dare wait much longer than the First. If we have to campaign much south of Prydon, the weather starts becoming treacherous around then.”

“True....” The Queen leaned back and put her boots up on the table. “I still hate to be raising force around this time of year. The wheat nee my attention: it’s no time for the Queen to be playing with armies....” She sighed. “But you’re right, it can’t be helped. And it must be settled quickly. I haven’t the resources to make this war twice. Herewiss, the last I heard, the Brightwood could field about three thousand people on short notice.”

“Closer to thirty-five hundred now, Queen. But do I take it correctly that you agree to my embassy to Prydon?”

“Oh, well, since Lorn seems to have this all planned out....”

“That part was my idea,” Herewiss said. “Someone has to see what the terrain looks like....”

Eftgan looked at him cockeyed. “And so you earn your name.” Freelorn saw Herewiss go slightly pale. Earning one’s name was not always a safe business. And “herewiss” in the Darthene meant “battle-wise,” and was used of tacticians or generals. “All right,” Eftgan said. “I can use, shall we say, a military attaché in Prydon. But Lorn, I want to know that you understand what you’re doing. First, Herewiss is not exactly inconspicuous. A man with the Fire—”

“Yes, a man with the Fire. Good. Let them see what they’re up against. Let them test him.”

The Queen sat back, looking thoughtful. “Lorn, there’s also the minor business of your relationship with him. They know that you two are lovers. They would know that he would be spying out the place for you, even if we hadn’t sent them defiance. And if they can find any way to do him harm... they will.”

“I know,” Freelorn said.

After a moment the Queen looked down. “Very well. Continue.”

“Don’t think me cruel,” Lorn said. “You agreed with me that it was time we stopped letting the battle be carried to us. What we have to do is walk right into the Shadow’s den and pull It by the beard—then stand up against the worst It sends, and afterwards, crush It. Rian in particular is an unknown quantity. We need to know what he can do, now. And the best way to find out is to wave Herewiss in his face.”

“He can’t refrain from me,” Herewiss said. “Power tests Power, always. And in this game as in any other, some advantage rests with the side that moves first. So... I go draw Rian out.” Khávrinen in its sheath was leaned up against his chair; the Fire about its hilts burned briefly higher, as if fuel had been thrown on it.

“And not just Rian,” Freelorn said. “Some ways, Herewiss is our banner—a symbol to the Shadow of all Its plans that the Goddess is destroying. It will definitely respond to his presence in Prydon.”

“It’d respond to mine, too,” Segnbora said from down the table. “Look, you two, you don’t dare waste me! I’m in breakthrough right now, and my Power’s running high, but it won’t be so forever. A month, maybe—then I’m no more to you than any other Rodmistress.”

“Oh, somewhat more....” said a voice that spoke without sound; and that end of the room did not so much grow dark, as seem to have been that way for a long time. The air there smelled of burning stone, and there were eyes in the dark again. “Yet I would not care to be wasted, either; my sdaha and I may be of some small use to you.”

Eftgan smiled. “Lhhw’Hasai, I had thought to ask you two—” Hasai laughed in the Dracon fashion, a sound like a small lake boiling over. “However many of you there are, then—I had thought to ask you what you felt you could do best in this campaign.”

“We’ll go ask the Dragons for help,” Segnbora said.

Those silver-burning eyes looked at her calmly, but there were misgivings in them. “Sdaha, we are guests in this world: refugees, here only by the mercy of the Immanence. Your kind was here first. We have long been careful to keep our intrusion in your lands and lives to the barest minimum. We do not become involved with humans.”

“Oh really?” Dritt said, dry. There was some muffled laughter up and down the table as Segnbora and her mindmate looked at each other.

“I told you, mdaha. You’re going to get that response everywhere we go. And about time.”

“So you think, indeed. But will llhw’Hreiha, the DragonChief, think so? What involves one Dragon involves us all.”

“Then it’s already too late,” Segnbora said. “We’re going to have to confront the Hreiha as soon as we can and get her approval.”

“Neither will her approval be as easy to come by as a king’s,” Hasai said. “She speaks for our whole kind: in her person she lives all our lives, all our ‘deaths’. Her decisions affect not only what we will be but what we have been—the sdahaih and mdahaih alike, what you call the ‘living’ and the ‘dead’. She may feel she needs time to make the decision. A hundred circlings of the sun or more, the last decision so major took. Then there were many bouts of nn’s’raihle to confirm it, and the Master-Choice at the end of the process....”

“That would put it into next year,” Freelorn said. “We can’t—”

; “Lorn, that would put it into the next century.” Segnbora was smiling, but the look was rueful. “We’ll just have to try to rush things a bit. And if she doesn’t approve....”

“One does not go against the lhhw’Hreiha.”

“One does if she’s about to get us all killed, mdaha....”

The room was still for a while, as silver eyes and hazel ones rested in each other, considering. “You are my sdaha, my living self,” Hasai said. “But life is intemperate; I must keep you from reckless choices.” The room grew full of what he meant—the presence of a terrible weight of years, of other Dracon souls and lives, now inextricably part of Segnbora, and intent on keeping her self and their selves in the world.

Segnbora nodded slowly. “Yes, you must. But I have to keep you from refusing to make any choice at all. Outliving the problem is no solution of it.” And she gazed at the Dragon and would not look away. The hair rose on Lorn’s neck as mortality, fierce and frail, and immortality, weighty and blunt as stone, leaned together and strove in the suddenly blistering air. Then the heat was gone, and there was unity; but it was troubled.

“You are my sdaha, dei’sithessch,” Hasai said. Segnbora looked down. “We shall try occasions with the DragonChief. We shall lose this battle, and perhaps save your kind and mine. But I’m of you, sdaha.”

Segnbora stared at the table with an expression abstracted and afraid; but she still wore a curl of smile. “What do you see?” Herewiss said, quiet-voiced.

Segnbora’s eyes came back to the present. She looked up. “Nothing clear,” she said. “I’m nearsighted, yet.... Sticks. Stones.” She shook her head. “Loss. Something found, and lost again....”

Eftgan glanced at him. “So that settles them,” she said. “Herewiss goes to Arlen with Sunspark. Segnbora goes in company too, though a bit more quietly. I go with an army and arrive on the first of Autumn; and there we all join forces, and take what adventure our Lady sends us. How are you going, Lorn?”

He swallowed. “Alone. I’ve been told. I have to go to Arlen to find my Initiation... and Hergótha and the Stave as well, I hope. If I survive, I’ll meet you afterwards. There’s no other way.”

No one said anything immediately. There was something about the silence that suggested some of them thought even the battle might not be a final solution. Lorn breathed out, and went on. “I’ll start somewhere southwards, and work north. They won’t be expecting that, either; they’ll expect me to rush into things headlong, as usual, the straight way along the Kings’ Road. Or else to try the midland route near Osta, as I did the last time.”

“You’re going to have to disguise yourself,” Eftgan said.

“I know.” He smiled slightly. “This place seems to be crawling with Rodmistresses and people with Fire. I should think you could come up with something.”

Eftgan nodded. Freelorn glanced over at Herewiss and found his loved looking at him with the strangest brooding expression, one that seemed to say, in astonishment and (most startling to Lorn) discomfort, At last, my loved is a man indeed... ! Freelorn strained for the underhearing that had been troubling him all morning. It refused to come, and he turned away to look at Eftgan, troubled at heart.

“Good enough,” she said. “Go your ways, my dears. We’ll talk more on this after dinner, with the Council. But I think we shouldn’t wait more than a few days to start.”

People got up, one by one, and headed out, while Freelorn sat still and studied the table.

“Lorn?”

He looked up. He and Eftgan were by themselves. A lark sailed singing past the high window, up into the blue air, till its song was lost.

“In seven years, nearly,” Freelorn said, “I haven’t been alone.”

Eftgan sighed, and got up. “When you’re a king, as far as people go, you’re alone all the time,” she said. “Did you think She gives kingship away for free?” She patted him on the shoulder as she went by on her way out. “But stay with it, my brother. It has its moments.”

Like that one just then, with Herewiss? he thought, as she left.

For several minutes Lorn sat there, and then got up and went out to see about his disguise.

In the grate, from the fire, eyes looked after him.

THREE

I think I love you,

and the problem

is the thinking.

d’Kaleth, Lament

There is a story that when the Maiden was making the world, She purposely dug the bed of the river Darst in a nearly complete circle around Mount Hirindë because She felt that the only thing needed to make its already splendid view perfect was water. As in other such stories, the truth is likely to be as complex as She. Mistress of the arts of war as well as those of peace, perhaps She was also thinking of the defensibility of such a hill, seven-eighths surrounded by a river a mile wide, full of treacherous shoals, and stretching out into great flats of wetland and bogland that would eat any attacking force alive. In any case, Darthis has never been taken by any foe, and the view is still unparalleled in the north country, particularly by moonlight.

Lorn stood there leaning on the low parapet of the Square Tower, the highest one in Blackcastle, looking southward across the town to the dull hammered-pewter gleam of the river, and the marshes rough and silvery under the first-quarter Moon. It was late, an evening a week after the Hammering. Under him the town was a scattering of streets dim in cresset-light, clusters of peaked roofs, the broad broken part-circle contour of the city’s second wall, long grown over and through with houses; here and there a tallow-glass or rushlight showed in a high window. The occasional voice, a shout of laughter or a snatch of song, drifted up through the cool air, coming and going as the wind shifted.

He swatted a hungry bug that was biting him earnestly in the neck, and looked out past the marshes, south, where patchwork fields and black blots of forest merged and melted together into a dark silver shimmer of distance: no brightness about them but a faint horizontal white line, the Kings’ Road, its pale stone running eastward in wide curves and vanishing into the mingling of horizon and night. It would be nice to be going that way, he thought. That was the way to the Brightwood, among other places. Four or five times he had ridden that road, sometimes with his father, on visits of state to the Wood... and later on his own business, for Herewiss’s boyhood home was there. A long time ago, that first visit with its arguments, its snubs, the standoffishness that shifted unexpectedly one night into friendship between a pair of preadolescent princes.

Lorn laughed softly at himself. He had thought Herewiss ludicrously provincial when he first saw him—a dark, scowling beanpole in a muddy jerkin, taciturn and scornful, and overly preoccupied with turnip fields: a “prince” living in an oversized log cabin, with a tree growing through its roof. What Herewiss had thought of him, with his fancy horse and his fancy sword and his fancy father, Freelorn had fortunately not found out until much later. There probably would have been bloodshed.

As it was, Lorn looked back at the memory in astonishment and wondered how he could ever have felt that way about Herewiss. He had been no prize himself. His princehood had just begun to mean something to him— “and too damned much of something!”, he could still hear his father growling, at the end of one memorable dressing-down. Lorn had succeeded in alienating just about everyone in the Brightwood on that first trip, including the one girl whose attention he had desperately been trying to attract. Crushed by a very public rejection, which had ended with pretty little Elen picking him up and dumping him headfirst into a watering trough, Lorn had bolted into the Brightwood, looking for a place to cry his heart out. Around nightfall he found a place, a clearing with a nice smooth slab of stone, and sat down there and wept because no one liked him.

Now he looked back for the hundredth time in calm astonishment at the circumstances that had brought Herewiss to find him, rather than the Chief Wardress of the Silent Precincts... for of course that was the spot he had picked to cry on: the holiest of altars to the G

oddess in perhaps the whole world, at the heart of those Precincts where no word is ever spoken by the Rodmistresses who train there, so that Her speech will be easier to hear. There Herewiss found him, and befriended him, almost more out of embarrassment than anything else, and got him out of there before they both got caught. And the friendship took, and grew fast.

Look at him, the thought came, in a rush of affection, sorrow, unease and desire, all run together in a bittersweet dissonance of emotion. And that second set of vision came upon Lorn again, so that he saw himself from behind, through Herewiss’s eyes as he came out on the tower’s roof. It was uncanny and disturbing. For what Herewiss saw wasn’t just a dark shape leaning on a parapet, but a much-loved embodiment of intent, and old pain, and warmth, and strife that would lead to triumph: a figure incomplete and annoying in some ways, but also heroic and sorrowfully noble—

The underhearing slipped off, leaving Lorn uncertain whether to laugh in affectionate scorn or cry with frustration. That’s not me!! he thought. Nevertheless he said nothing, and held still until his loved had joined him. They leaned on the wall together, shoulders touching, looking out southward to where the fields melted into silver-black sky.

“When I first met you that time,” Lorn said, “were you trying to grow a mustache?”

Herewiss began to laugh. “After fifteen years, you ask me that now?”

“Well, I was just remembering, and all of a sudden I remembered this thing on your lip.”

Herewiss laughed harder. “Oh, Goddess. Yes, I was. I’d been working on it for months. But then you arrived, and you had one, so I shaved mine right off.”

Lorn chuckled. “And then Elen told me to grow it back or she’d have nothing to do with me,” Herewiss said. “So I did. I doubt there was much of it there when I found you, though.”

The Book of Night With Moon

The Book of Night With Moon A Wind From the South

A Wind From the South A Wizard Abroad, New Millennium Edition

A Wizard Abroad, New Millennium Edition Lior and the Sea

Lior and the Sea Uptown Local and Other Interventions

Uptown Local and Other Interventions High Wizardry New Millennium Edition

High Wizardry New Millennium Edition Games Wizards Play

Games Wizards Play Wizard's Holiday, New Millennium Edition

Wizard's Holiday, New Millennium Edition So You Want to Be a Wizard, New Millennium Edition

So You Want to Be a Wizard, New Millennium Edition The Door Into Sunset

The Door Into Sunset To Visit the Queen

To Visit the Queen A Wizard Abroad

A Wizard Abroad Not on My Patch

Not on My Patch The Door Into Shadow

The Door Into Shadow The Door Into Fire

The Door Into Fire A Wizard Alone New Millennium Edition

A Wizard Alone New Millennium Edition The Tale of the Five Omnibus

The Tale of the Five Omnibus The Wizard's Dilemma, New Millennium Edition

The Wizard's Dilemma, New Millennium Edition The Big Meow

The Big Meow Wizards at War, New Millennium Edition

Wizards at War, New Millennium Edition Interim Errantry

Interim Errantry Omnitopia: Dawn

Omnitopia: Dawn High Wizardry

High Wizardry Spider-Man: The Venom Factor Omnibus

Spider-Man: The Venom Factor Omnibus Spider-Man: The Venom Factor

Spider-Man: The Venom Factor Seaquest DSV

Seaquest DSV How Lovely Are Thy Branches

How Lovely Are Thy Branches So You Want to Be a Wizard

So You Want to Be a Wizard Midnight Snack and Other Fairy Tales

Midnight Snack and Other Fairy Tales Stealing the Elf-King's Roses

Stealing the Elf-King's Roses Interim Errantry 2: On Ordeal

Interim Errantry 2: On Ordeal Raetian Tales 1: A Wind from the South

Raetian Tales 1: A Wind from the South Starrise at Corrivale h-1

Starrise at Corrivale h-1 The Wizard's Dilemma

The Wizard's Dilemma Sand and Stars

Sand and Stars How Lovely Are Thy Branches: A Young Wizards Christmas

How Lovely Are Thy Branches: A Young Wizards Christmas On Her Majesty's Wizardly Service fw-2

On Her Majesty's Wizardly Service fw-2 X-COM: UFO Defense

X-COM: UFO Defense Star Trek: The Original Series: Rihannsu, Book 5: The Empty Chair

Star Trek: The Original Series: Rihannsu, Book 5: The Empty Chair seaQuest DSV: The Novel

seaQuest DSV: The Novel Stealing the Elf-King's Roses: The Author's Cut

Stealing the Elf-King's Roses: The Author's Cut Not On My Patch: a Young Wizards Hallowe'en Story

Not On My Patch: a Young Wizards Hallowe'en Story A Wizard Alone yw[n&k-6

A Wizard Alone yw[n&k-6 The Bloodwing Voyages

The Bloodwing Voyages Games Wizards Play (Young Wizards Series)

Games Wizards Play (Young Wizards Series) The Book of Night with Moon fw-1

The Book of Night with Moon fw-1 My Enemy My Ally

My Enemy My Ally Dark Mirror

Dark Mirror Star Trek: The Original series: Rihannsu: The Bloodwing Voyages

Star Trek: The Original series: Rihannsu: The Bloodwing Voyages Deep Wizardry yw[n&k-2

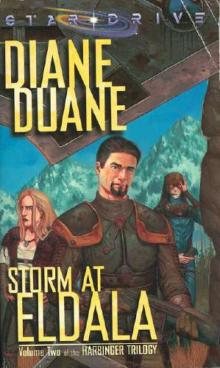

Deep Wizardry yw[n&k-2 Storm at Eldala h-2

Storm at Eldala h-2