- Home

- Diane Duane

On Her Majesty's Wizardly Service fw-2 Page 4

On Her Majesty's Wizardly Service fw-2 Read online

Page 4

Rhiow sighed. The human school year was just starting, and ehhif businesses were swinging back into full operation after the last of their people came back from vacation … The City was sliding back into fully operative mode, which meant increased pressure on the normal rapid transit. That in turn meant more stress on the gates, for the increased numbers of ehhif moving in and out of the City meant more stress on the fabric of reality, especially in the areas where large numbers of people flowed in and out in the vicinity of the gate matrices themselves. String structure got finicky, matrices got warped and gates went down without warning at such times: hardly a day went by without a malfunction. The Pennsylvania Station gating team had their paws full just with their normal work. Having the Grand Central gates added to their workload, at their busiest time…

“Ruah, it can’t be helped,” Rhiow said. “They can take it up with the Powers themselves, if they like, but the Whisperer will send them off with fleas in their ears and nothing more. These things happen.”

“Yeah, well, what about you?”

“Me?”

“You know. Your ehhif.”

Rhiow sighed at that. Urruah was “nonaligned”—without a permanent den and not part of a pride-by-blood, but most specifically uncompanioned by ehhif, and therefore what they would call a “stray”: mostly at the moment he lived in a dumpster outside a construction site in the East Sixties. Arhu had inherited Saash’s position as mouser-in-chief at the underground parking garage where she had lived, and had nothing to do to keep in good odor with his “employers” except, at regular intervals, to drop something impressively dead in front of the garage office, and to appear fairly regularly at mealtimes. Rhiow, however, was denned with an ehhif in an twentieth-story apartment between First and Second in the Seventies. Her comings and goings during his workday were nothing which bothered Iaehh, since he didn’t see them: but in the evenings, if he didn’t know where she was, he got concerned. Rhiow had no taste for upsetting him—between the two of them, since the sudden loss of her “own’ ehhif, Hhuha, there had been more than enough upset to go around.

“I’ll have to work around him the best I can,” she said. “He’s been doing a lot of overtime lately: that’ll probably help me.” Though as she said it, once again Rhiow found herself wondering about all that overtime. Was it happening because the loss of the household’s second income had been making the apartment harder to afford, or because the less time Iaehh spent there, being reminded of Hhuha in the too-quiet evenings, the happier he was … ? “And besides,” she said, ready enough to change the subject, “it can’t be any better for you …”

Urruah made a hmf sound. “Well, it’s annoying,” he said. “They’re starting H’la Houheme at the end of the week.”

“I don’t mean that. I had in mind your ongoing business with the ‘Somali’ lady you’ve been seeing over at the Met. The diva-ehhifs ‘pet’.”

Urruah shook his head hard enough that his ears rattled slightly. It was a gesture Rhiow had been seeing more often than usual from him, lately, and he had picked up a couple more scars about the head. “Yes, well,” he said.

Rhiow looked away and began innocently to wash. Urruah’s interest in the artform known to ehhif as “opera” continued to strike her as a little kinky, despite Rhiow’s recognition that this was simply a slightly idiosyncratic personal manifestation of all toms’ fascination with song in its many forms. However, lately Urruah had been discoursing less in the abstract mode as regarded oh’ra, and more about the star dressing room and the goings-on therein. Urruah’s interest in Hwith was apparently less than abstract, and appeared mutual, though most of what Rhiow heard of Hwith’s discourse had to do with the juicier gossip about her “mistress’s” steadily intensifying encounters with the oh’ra’s present guest conductor.

“Well, what the hiouh,” Urruah said after a moment, “this is what we became wizards for, anyway, isn’t it? Travel. Adventure. Going to strange and wonderful places …”

And getting into trouble in them, Rhiow thought. “Absolutely,” she said. “Come on … let’s start getting the logistics sorted out.”

She turned and walked back up the platform, jumped down onto the tracks and started to make her way over the iron-stained gravel to the platform for Track Twenty-Four. Urruah followed at his own pace: Arhu leapt and ran to catch up with her. “Why’re you so down about it?” he said. “This is gonna be great!”

“It will if you don’t act up,” Rhiow said, and almost immediately regretted it.

“Whaddaya mean, ‘act up’? I’m very well behaved.”

Rhiow gave Urruah a sidewise look as he came up from behind them. “Compared to the Old Tom on a rampage,” she said, “or the Devastatrix in heat, doubtless you are. As People go, though, we have some work to do on you yet.”

“Listen to me, Arhu,” Urruah said, as they jumped up onto Track Twenty-Four and started weaving their way down it toward the entrance to the Main Concourse. “We’re going into other People’s territory. That’s always ticklish business. Not only that: we’re going there because there’s something going on that they couldn’t handle by themselves. They have to have feelings about that … and that we’re now going to come strolling in there with our tails up to fix things, supposedly, can’t make them overjoyed either. It makes them look bad to themselves. You get it?”

“Well, if they are bad—”

Arhu broke off and ducked out of the way of the swipe Rhiow aimed at his head. “Arhu,” Rhiow said, “that’s not your judgment to make. Certainly not of another wizard: not of regular People, either. Queen Iau has built us all with different abilities, and just because they don’t always work perfectly right now doesn’t mean they won’t later. As for their effectiveness: sometimes a wizard comes up against a job he can’t handle. When that happens, and we’re called to assist, we do just that … knowing that someday we may be in the same position.”

They came out of the gateway to Twenty-Four, squeezing hard to the left to avoid being trampled by the ehhif who were streaming in toward the waiting train, and came out into the Concourse. “We’re a kinship, not a group of competitors,” Urruah said, as they began making their way toward the Graybar Building entrance, hugging the wall. “We don’t go out of our way to make our brothers and sisters feel that they’re failing at their jobs. We fail at enough of our own.”

“So,” Rhiow said. “We’ve got a day or so to sort out our own business. Urruah, fortunately, doesn’t have an abode shared with ehhif, so his arrangements will be simplest—”

“Hey, listen,” Urruah said, “if I go away and they take my dumpster somewhere, you think that isn’t going to be a problem? I’ll have to drop back here every couple of days to make sure things stay the way I left them.”

Rhiow restrained herself mightily from asking what Urruah could possibly keep in a dumpster that was of such importance. “Arhu, at the garage, have any of them been paying particular attention to you?”

“Yeah, the tall one,” he said, “Ah’hah, they call him. He was Saash’s ehhif, he seems to think he’s mine now.” Arhu looked a little abashed. “He’s nice to me.”

“OK. You’re going to have to come back from London every couple of days to make sure that he sees you and knows you’re all right.”

“By myself?” Arhu said, very suddenly.

“Yes,” Rhiow said. “And Arhu—if I find, that in the process you’ve gated off-planet, your ears and my claws are going to meet! Remember what Urruah told you.”

“I never get to have any fun with wizardry!’ Arhu said, the complaining acquiring a little yowl around the edges, and he fluffed up slightly at Rhiow. “It’s all work and dull stuff!”

“Oh really?” Urruah said. “What about that cute little marmalade tabby I saw you with the other night?”

“Uh … Oh,” Arhu said, and abruptly sat down right by the wall and became very quiet.

“Yes indeed,” Urruah said. “Naughty business, that, stealing

groceries out of an ehhif’s trunk. That’s why you fell down the manhole afterwards. The Universe notices when wizards misbehave. And sometimes … other wizards do too.”

Arhu sat staring at Urruah wide-eyed, and didn’t say anything. This by itself was so bizarre an event that Rhiow nearly broke up laughing. “Boy’s got taste, if nothing else,” Urruah said to her, and sat down himself for a moment. “He was up on Broadway and raided some ehhifs shopping bags after they’d been to Zabar’s. Caviar, it was, and smoked salmon and sour cream: supposed to be someone’s brunch the next day, I guess. He did a particulate bypass spell on a section of the trunk lid and pulled the stuff out piece by piece … then gave every bit of it to this little marmalade creature with big green eyes.”

Arhu was now half-turned away from them while hurriedly washing his back. It was he’ihh, composure-washing: and it wasn’t working—the fur bristled again as fast as he washed it down. “Never even set the car alarm off,” Urruah said, wrapping his tail demurely around his toes. “Did it in full sight. None of the ehhif passing by believed what they were seeing, as usual.”

“I had to do it in full sight,” Arhu said, starting to wash further down his back. “You can’t sidle when you’re—”

“—stealing things, no,” Rhiow said, as she sat down too. She sighed. The child had come to them with a lot of bad habits. Yet much of his value as a Person and a wizard had to do with his unquenchable, sometimes unbearable spirit and verve, which even a truly awful kittenhood had not been able to crush. Had his tendencies as a visionary not already revealed themselves, Rhiow would have thought that Arhu was destined to be like Urruah, a “power source”, the battery or engine of a spell which others might construct and work, but which he would fuel and drive. Either way, the visionary talent too used that verve to fuel it. It was Arhu’s inescapable curiosity, notable even for a cat, which kept his wizardry fretting and fraying at the fabric of linear time until it “wore through” and some image from future or past leaked out.

“If nothing else,” Rhiow said finally, “you’ve got a quick grasp of the fundamentals … as they apply to implementation, anyway. I can see the ethics end of things is going to take longer.” Arhu turned, opened his mouth to say something. “Don’t start with me,” Rhiow said. “Talk to the Whisperer about it, if you don’t believe us: but stealing is only going to be trouble for you eventually. Meanwhile, where shall we meet in the morning?”

Urruah looked around him as Arhu got up again, looking a little recovered. “I guess here is as good a place as any. Five thirty?”

That was opening time for the station, and would be fairly calm, if any time of the day in a place as big and busy as Grand Central could accurately be described as calm. “Good enough,” Rhiow said.

They started to walk out down the Graybar Passage again, to the Lexington Avenue doors. “Arhu?” Rhiow said to him as they came out and slide sideways to hug the wall, heading for the corner of Forty-Third. “An hour before first twilight, two hours before the Old Tom’s Eye sets.”

“I know when five thirty is,” Arhu said, sounding slightly affronted. They do shift change at the garage a moonwidth after that.”

“All right,” Urruah said. “Anything else you need to take care of, like telling the little marmalade number—”

“Her name’s Hffeu,” Arhu said.

“Hffeu it is,” Rhiow said. “She excited to be going out with a wizard?”

Arhu gave Rhiow a look of pure pleasure: if his whiskers had gone any further forward, they would have fallen off in the street.

She had to smile back: there were moods in which this kit was, unfortunately, irresistible. “Go on, then—tell her goodbye for a few days: you’re going to be busy. And Arhu—”

“I know, ‘be careful’.” He was laughing at her. “Luck, Rhiow.”

“Luck,” she said, as he bounded off across the traffic running down Forty-Third, narrowly being missed by a taxi taking the corner. She breathed out. Next to her, Urruah laughed softly as they slipped into the door of the post office to sidle, then waited for the light to change. “You worry too much about that kit. He’ll be all right.”

“Oh, his survival is between him and the Powers now,” she said, “I know. But still …”

“ … you still feel responsible for him,” Urruah said as the light turned and they trotted out to cross the street, “because for a while he was our responsibility. Well, he’s passed his Ordeal, and we’re off that hook. But now we have to teach him teamwork.”

“It’s going to make the last month look like ten dead birds and no one to share them with,” Rhiow said. She peered up Lexington, trying to see past the hurrying ehhif. Humans could not see into that neighboring universe where cats went when sidled and in which string structure was obvious, but she could just make out Arhu’s little black-and-white shape, trailing radiance from passing resonated hyperstrings as he ran.

“At least he’s willing,” Urruah said. “More than he was before.”

“Well, we owe a lot of that to you … your good example.”

Urruah put his whiskers forward, pleased, as they came to the next corner and went across the side street at a trot. “Feels a little odd sometimes,” he said.

“What,” Rhiow said, putting hers forward too, “that the original breaker of every available rule should now be the big, stern, tough—”

“I didn’t break that many rules.”

“Oh? What about that dog, last month?”

“Come on, that was just a little fun.”

“Not for the dog. And the sausage guy on Thirty-Third—”

“That was an intervention. Those sausages were terrible.”

“As you found after tricking him into dropping one. And last year, the lady with the—”

“All right, all right!’ Urruah was laughing as they came to Fifty-Fifth. “So I like the occasional practical joke. Rhi, I don’t break any of the real rules. I do my job.”

She sighed, and then bumped her head against his as they stood by the corner of the building at Forty-Fifth and Lex, waiting for the light to change. “You do,” she said. “You are a wizard’s wizard, for all your jokes. Now get out of here and do whatever you have to do with your dumpster.”

“I thought you weren’t going to mention that,” Urruah said, and grinned. “Luck, Rhi—”

He galloped off across the street and down Forty-Fifth as the light changed, leaving her looking after him in mild bemusement.

He heard me thinking.

Well, wizards did occasionally overhear one another’s private thought when they had worked closely together for long enough. She and Saash had sometimes “underheard” each other this way: usually without warning, but not always at times of stress. It had been happening a little more frequently since Arhu came. Something to do with the change in the make-up of the team? … she thought. There was no way to tell.

And no time to spend worrying about it now. But even as Rhiow set off for her own lair, trotting on up Lex toward the upper East Side, she had to smile ironically at that. It was precisely because she was so good at worrying that she was the leader of this particular team. Losing the habit could mean losing the team … or worse.

For the time being, she would stick to worrying.

The way home was straightforward, this time of day: up Lex to Seventieth, then eastward to the block between First and Second. The street was fairly quiet for a change. Mostly it was old converted brownstones, though the corner apartment buildings were newer ones, and a few small cafes and stores were scattered along the block. She paused at the corner of Seventieth and Second to greet the big stocky duffel-coated doorman there, who always stooped to pet her. He was opening the door for one of the tenants: now he turned, bent down to her. “Hey there, Midnight, how ya doing?”

“No problems today, Ffran’kh,” Rhiow said, rearing up to rub against him: he might not hear or understand her spoken language any more than any other ehhif, but body language he und

erstood just fine. Ffran’kh was a nice man, not above slipping Rhiow the occasional piece of baloney from a sandwich, and also not above slipping some of the harder-up homeless people in the area a five- or ten-dollar bill on the sly. Carers were hard enough to come by in this world, wizardly or not, and Rhiow could hardly fail to appreciate one who was also in the neighborhood.

Having said hello in passing, she went on her way down the block, not bothering to sidle even this close to home. Iaehh rarely came down the block this way anyhow, preferring for some reason to approach from the First Avenue side, possibly because of the deli down on that corner. She strolled down the sidewalk, glancing around her idly at the brownstones, the garbage, the trees and the weeds growing up around them; more or less effortlessly she avoided the ehhif who came walking past her with shopping bags or briefcases or baby strollers. Halfway down was a browner brownstone than usual, with the usual stairway up to the front door and a side stairway to the basement apartment. On one of the squared-off tops of the stone balusters flanking the stairway sat a rather grungy looking white-furred shape, washing. He was always washing, Rhiow thought, not that it did him any good. She stopped at the bottom of the stairs.

“Hunt’s luck, Yafh!”

He looked down at her and blinked for a moment. Green eyes in a face as round as a saucer full of cream, and almost as big: big shoulders, huge paws, and an overall scarred and beat-up look, as if he had had an abortive argument with a meat grinder: that was Yafh. However, you got the impression that the meat grinder had lost the argument. “Luck, Rhi,” he said cheerfully. “I’ve had mine for today. Care for a rat?”

“That’s very kind of you,” she said, “but I’m on my way to dinner, and if I spoil my appetite, my ehhif will notice. Bite its head off on my behalf, if you would …”

“My pleasure.” Yafh bent down and suited the action to the word.

She trotted up the steps and sat down beside Yafh for a moment, looking down the street while he crunched. Yafh was one of those People who, while ostensibly denned with ehhif, was neglected totally by them. He subsisted on stolen scraps scavenged from the neighborhood garbage bags, and on rats and mice and bugs—not difficult in this particular building, its landlord apparently not having had the exterminators in since early in the century.

The Book of Night With Moon

The Book of Night With Moon A Wind From the South

A Wind From the South A Wizard Abroad, New Millennium Edition

A Wizard Abroad, New Millennium Edition Lior and the Sea

Lior and the Sea Uptown Local and Other Interventions

Uptown Local and Other Interventions High Wizardry New Millennium Edition

High Wizardry New Millennium Edition Games Wizards Play

Games Wizards Play Wizard's Holiday, New Millennium Edition

Wizard's Holiday, New Millennium Edition So You Want to Be a Wizard, New Millennium Edition

So You Want to Be a Wizard, New Millennium Edition The Door Into Sunset

The Door Into Sunset To Visit the Queen

To Visit the Queen A Wizard Abroad

A Wizard Abroad Not on My Patch

Not on My Patch The Door Into Shadow

The Door Into Shadow The Door Into Fire

The Door Into Fire A Wizard Alone New Millennium Edition

A Wizard Alone New Millennium Edition The Tale of the Five Omnibus

The Tale of the Five Omnibus The Wizard's Dilemma, New Millennium Edition

The Wizard's Dilemma, New Millennium Edition The Big Meow

The Big Meow Wizards at War, New Millennium Edition

Wizards at War, New Millennium Edition Interim Errantry

Interim Errantry Omnitopia: Dawn

Omnitopia: Dawn High Wizardry

High Wizardry Spider-Man: The Venom Factor Omnibus

Spider-Man: The Venom Factor Omnibus Spider-Man: The Venom Factor

Spider-Man: The Venom Factor Seaquest DSV

Seaquest DSV How Lovely Are Thy Branches

How Lovely Are Thy Branches So You Want to Be a Wizard

So You Want to Be a Wizard Midnight Snack and Other Fairy Tales

Midnight Snack and Other Fairy Tales Stealing the Elf-King's Roses

Stealing the Elf-King's Roses Interim Errantry 2: On Ordeal

Interim Errantry 2: On Ordeal Raetian Tales 1: A Wind from the South

Raetian Tales 1: A Wind from the South Starrise at Corrivale h-1

Starrise at Corrivale h-1 The Wizard's Dilemma

The Wizard's Dilemma Sand and Stars

Sand and Stars How Lovely Are Thy Branches: A Young Wizards Christmas

How Lovely Are Thy Branches: A Young Wizards Christmas On Her Majesty's Wizardly Service fw-2

On Her Majesty's Wizardly Service fw-2 X-COM: UFO Defense

X-COM: UFO Defense Star Trek: The Original Series: Rihannsu, Book 5: The Empty Chair

Star Trek: The Original Series: Rihannsu, Book 5: The Empty Chair seaQuest DSV: The Novel

seaQuest DSV: The Novel Stealing the Elf-King's Roses: The Author's Cut

Stealing the Elf-King's Roses: The Author's Cut Not On My Patch: a Young Wizards Hallowe'en Story

Not On My Patch: a Young Wizards Hallowe'en Story A Wizard Alone yw[n&k-6

A Wizard Alone yw[n&k-6 The Bloodwing Voyages

The Bloodwing Voyages Games Wizards Play (Young Wizards Series)

Games Wizards Play (Young Wizards Series) The Book of Night with Moon fw-1

The Book of Night with Moon fw-1 My Enemy My Ally

My Enemy My Ally Dark Mirror

Dark Mirror Star Trek: The Original series: Rihannsu: The Bloodwing Voyages

Star Trek: The Original series: Rihannsu: The Bloodwing Voyages Deep Wizardry yw[n&k-2

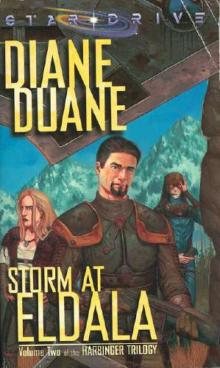

Deep Wizardry yw[n&k-2 Storm at Eldala h-2

Storm at Eldala h-2