- Home

- Diane Duane

The Tale of the Five Omnibus Page 26

The Tale of the Five Omnibus Read online

Page 26

A howling. A sick ugly howling like an axe being sharpened too long, and mixed with it other sounds, human voices crying out in terror, the sound of scrabbling claws and—

Herewiss tried to stand up. The binding spell. Broken. A pack of hralcins; the one had gone back for reinforcements. A touch too much stress on the binding somehow. The spell broken, and now all of them loose, hunting. Hunting him. But he hadn’t been in his body. So they couldn’t find him. But they had found something else to hold them until he returned. Freelorn. Freelorn’s people. Downstairs. Defenseless.

He tried to stand again, and it didn’t work. Too much drug. Out of it too suddenly. His body disobeyed him, and responded to his commands with vengeful stabs of pain. The screaming was louder, voices terrified beyond understanding. He refused to let his body’s punishments stop him. There was a little light now, sickly, the light of the Moon almost gone down. Against the wall was a dim gray blot, the only thing he could really see. He made a hand go out, despite shrieking protests from his head and arm and aching torso, and took hold of the thing. It swayed in his grasp. The other hand, now. He gripped the object hard, and wrenched himself to a sitting position next to it.

If his voice could have found his throat, he would have screamed. It was the sword, sharpened that morning, and it cut into his hands in icy lines of pain, and the blood flowed. But he had no time, no time for the pain, and he struggled to stand, using the sword as a prop. He moved his hands feebly to the unsharpened tang, where the hilt would go, and pushed himself up, and somehow managed to stand. His legs wobbled under him as if they belonged to a body he had owned in a former life. He made his feet move. He went to the door.

The stairs were dark, and Herewiss fell and stumbled down them, using the sword as a cane, caroming off the walls with force enough to bruise bones—though he couldn’t feel the blows much through the shell which the drug had made of his body. The cries of men in terror were closer now. They mingled with that awful lusting hunger-howl and were nearly lost in it, faint against it as against the laughter of Death. As Herewiss came to the landing at the foot of the stairs, very faintly he could see some kind of light coming from the main hall, a fitful light, coming in stuttered and flashes. With every flash the hralcins screeched louder in frustration and rage. Segnbora! he thought. She’s holding them off with the light until I can get there. But what can I do? Nothing but Flame would do anything—

He reeled against the wall to rest his blazing body for a second, and the answer spoke itself to him in his brother’s voice: “It’ll turn in your hand unless you acquit yourself of my ‘murder.’”

He stumbled away from the wall and went on again, shuffling, hurrying, pushing himself through the pain. The light before him grew brighter as he approached the hall, but the flashes were becoming shorter and shorter. Segnbora spoke of choosing when to listen to the voices of the dead—and when you can choose freely, and not be driven by them, you’re free to find out who you really are— And the voice spoke again in the back of his mind, saying, “There’s neither lying nor deception, back of the Door—”

He couldn’t lie, Herewiss thought through the effort of making his body work. He was telling the truth. He was! I didn’t—

He came to the doorway of the hall, and stood there, trembling with fear and effort, taking in the scene. There was little sound from the people in the hall now. They were crowded together in one corner, huddled together with closed or averted eyes. Before them stood Segnbora, arms upraised, shaking terribly, but with a look of final commitment on her face as she summoned the Flame from the depths of her, brilliant and impotent. As Herewiss watched, supporting himself on the bloody sword, she called the light out of herself again. But this time there was no starflower, no burst of blue: only a rather bright light, quickly gone.

In that light he could see the huge things she was holding off, as they backed away a bit. They reached out with twisted limbs, black talons raked the air like the combed claws of insects. Even through their banshee wail the sound of sheathed fangs moving hungrily in hidden mouths could still be heard. The light seemed to refuse to touch them, sliding away from hide the color of night with no stars—though there were baleful glitters from where their eyes could have been, reflections the color of gray-green stormlight on polished ice. The air in the room was bitter cold, and smelled of rust and acid.

The light flickered out, and the hralcins moved in again for their meal.

Herewiss staggered in, into the thick darkness. Well, maybe this was what he was for. The hralcins had come after him: he would give himself to them, and they would feed on his soul and go away, satisfied. His friends would escape. He found himself suddenly glad of those few precious moments with his brother, however painful they had been. After the hralcins were through with him, there would be nothing. No silent shore, no Sea of light, no rebirth ever; only terrible pain, and then the end of things. But if this was going to be the last expression of his existence, he would do it right. He drew himself up straight, though it hurt, and lifted up the sword. Almost he smiled: it was so good to face his fears at last—!

“Here I am, you sons of bitches!” he yelled. “Come and get me!”

The howling paused for a moment, as if in confusion—and then, to Herewiss’s utter horror, resumed again. They were not interested. They had found other game; they would take the souls of Freelorn and his people, and then later have Herewiss at their leisure.

“No,” he breathed. “No—”

“Herewiss!” two voices cried at once, and there was the light again, but only a shadow of itself, pallid and exhausted. Segnbora held up her arms with fists clenched, as if she were trying to hold onto the light by main force, while her eyes searched the shadows for Herewiss. Freelorn stood apart from her, grim-faced and terrified. His sword was naked in his hand: a useless gesture, but one that described him in full. That man walked the land of the dead with me unafraid, Herewiss thought, and here he is facing down things that’ll drink him up, blood and soul together, and he’s afraid, and still he defies—!

The light died out, for the last time. The hralcins howled, and moved in—

The hall exploded into fire, an awful blaze of white-hot outrage. Freelorn and Segnbora and the others crowded further back into the corner as Sunspark flowered between them and the hralcins, its fires raging upward in a terrible blinding column until they smote the ceiling and turned back on themselves, the down-hanging branches of a tree of flames. The hralcins backed away again.

“Sunspark,” Herewiss cried, the sound of his shout hurting his head. “Spark, no, don’t—”

The hralcins were already sliding closer again. (Herewiss,) it said, lashing out at them with great gouts of fire, (he loves you. And you love him, more than you do me, I dare say. How shall I stand by and allow him to be taken from you? And then afterwards these things would take you too—) Its thoughts were casual on the surface, almost humorous, but beneath them Herewiss could hear its terror for him.

“Spark—!”

It went up in so unbearable a glare that Herewiss had to close his eyes, but before he did he saw that the hralcins were still moving closer. (They don’t seem to be responding as well as before to this,) it said conversationally, while beneath the thought all its self sang with fear. (I think—)

There was a sudden shocked silence. Herewiss opened his eyes again to see one of the hralcins reach out and somehow tear the pillar of fire in two, hug a great tattered blaze of light to itself with its misshapen forelimbs, suck it dry, kill the light. The other hralcins moved in for the rest, tore at the light, fed, consumed it, darkness fell—

“SUNSPAAAAAARK!”

The hralcins howled like the Shadow’s hounds, and moved in again. And through the howling, Herewiss heard Freelorn scream.

The scream entered into Herewiss and burned behind his eyes, ran through his veins in a storm of fire and filled him as the drug had filled him with himself. He needed his Name. There was no time any more.

He threw the door open, and looked. Time froze in him. No, he froze it—

All his life he had thought of time as being flat, like a plane. It was the world that was three-dimensional. A moment had seemed to have an edge sharp enough to slice a finger on, and by the time he summoned up the self-awareness and desire to try balancing on such a razor’s edge, the moment was past already, and he was teetering on the next one.

Now, though, he found himself poised there, effortlessly, in the exact middle of a moment. And since he was truly still for the first time in his life, he perceived his Name. He looked sideways down it, or along it, or into it—there were no words to properly express the spatial relationships implicit within its structure. Its strands stretched outward forever, and inward forever, flung out to eternity and yet curling back and meeting themselves again, making a whole. A scintillating, dazzling latticework of moments past and moments future, of Herewiss-that-was and Herewiss-that-would-be, all entwined, all coexisting; a timeweb, a selfweb, himself at its heart.

He looked up and down its length, and saw. Down there, root and heart and anchor-point of the weave, the night of his conception. Elinádren his mother, and Hearn his father, tangled sweetly together in the act of love. After some time of sleeping together for the sheer fun of the sharing, they were making an amazing discovery; that each of them was finding the other’s delight more joyous than his or her own—and not just while in bed. The long comfortable friendship of the Lord’s son and the Rodmistress who worked with him had come to fruition; they had become lovers; and now that they were in love indeed, their Names were beginning to match in places. He could see the two brilliant Name-weaves tangling through one another, and where they touched and met and melded, they blazed white-hot with joy. It was as if someone had cast out a net of silver and drawn in a catch of stars.

Herewiss’s soul, existing in timelessness, saw that bright network and was entranced by it; the joystars were beacons that drew him in. He wanted that kind of joy, of love, wanted to be part of it, to share the joy with someone else that way. And as he watched, Elinádren exploded in ecstatic fulfillment, and her Fire ran searing through the glittering weave, igniting the joystars into unbearable blinding brilliance, setting free for a bare few moments the spark of Hearn’s suppressed Flame, which swept down like wildfire to meet hers. Their two commingled souls burned starblue, and Herewiss, overwhelmed by an ecstasy of light and promised joy, dove inward and blazed into oneness with them as they were one; started to be born again….

And other occurrences, later ones. Being held in his father’s arms, carried home half-asleep after his presentation at the Forest Altars: three years old. “Oh,” Hearn’s voice whispering to Elinadren, who walked beside them with her arm through Hearn’s, moving quietly through green twilight, “oh, Eli, he’s going to be something special.”

And another one over there, watching his mother make it rain to stave off what seemed an incipient dry spell. He was six years old. Watching her stand there in the field, garlanded with meadowsweet to invoke the Mother of Rains, seeing her uplift a Rod burning with the Fire and call the rainclouds to her with Flame and poetry. He watched the sky darken into curdled contrasts, clouds violet and orange and stormgreen, watched her bring the lightning-licked water thundering down, and a great desire to control the things of the world rose up in him. He got up from the grass, soaking wet, and went to hold onto Elinádren’s skirts, and said, “Mommy, I’ll do that when I grow up too!”

And yet another, when he was out camping in the grasslands east of the Wood, and he woke up and stretched in the morning to find the grass-snake coiled in the blankets with him, and heard its warning hiss: eleven years old. He knew it could kill him; and he knew he could probably kill it, for his knife was close to hand and he was fast. But he remembered Hearn saying, “Don’t ever kill unless you must!”—and he lifted up the blankets slowly and then rolled out, and from beneath them the grass-snake streaked out like a bright green lash laid over the ground, and was gone, as frightened of him as he had been of it. I guess you can do without killing, he thought. Always, from now on, I’ll try—

There were thousands more moments like that, each one of which had made him part of what he was, each linked to all the moments before and all the moments after, making the bright complete framework that was his Name. And each act or decision had a shadow, a phantom link behind it—sprung from his deeds, yet independent of them somehow—another Name, shadowing itself in multiple reflections, reaching out into depths he could not fully comprehend—

Her Name. The Goddess’s. Of course.

No wonder She wanted to free me. And no wonder She wanted my Name. Not power, nothing so simple. It is part of Hers. Her Name is the sound of all Names everywhere. And with the knowledge of my Name, She will win ever so slight a victory against the Death. There will be more of Her than there was; the sure knowledge of what I am at this moment in time will make me immortal in a way that will surpass and outlast even the cycles of death and rebirth, even the great Death of everything that is.

If I accept myself—

Herewiss stood there in the midst of the blazing brilliance of the weave, hearing words long forgotten as well as ones that had never been spoken, tasting joys he had ceased to allow himself and pains he had shut away, and also feeling with wonder the textures of things that hadn’t happened yet, silks and thorns and winds laden with sunheat like molten silver— Whether the drug was still working in him, he wasn’t sure; but futures spun out ahead of him from the base-framework of his Name, numberless probabilities. Some of them were so faint and unlikely that he could hardly perceive them at all; some were almost as clear as things that had become actuality. Some of these were dark with his death, and some almost as dark with his life; one burned blue with the Fire, and he looked closely at it, saw himself almost lost in light, rippling with Flame that streamed from him like a cloak in the wind. And that future was ready to start in the next moment, when he let time start happening again. But there was still a gap in the information, he didn’t know how to get there from here—

Yes I do.

Herewiss looked forward along all the futures, and back down his past, weighing the brights and darks of them, and accepted them for his.

And knew his Name.

And knew the Name of his fear.

His Flame, of course. There it lay, dying indeed, but still the strongest thing about him, the strongest part of him. How long, now, had he been trying to control it, to use it like a hammer on the anvil of the world? The blue Flame was not something to be used in that fashion. He had been trying to keep it apart from him, where it would not be a threat to his control of himself If he wanted it, really wanted it, he was going to have to take hold of it and merge himself with the Fire, give up the control, yield himself wholly and forever.

It was going to hurt. The fires of the forge, of a star’s core, of an elemental’s heart would be nothing compared to this.

So be it. There’s no more time. I’ve got to do it.

He had been trying to make it his.

He reached out and embraced it, and made it him.

Pain, incredible pain for which the anguished screaming of a whole dying world seemed insufficient expression. He hung on, grasped, held, was fire—and then time began to reassert itself, the pain mixing with the sound of Freelorn’s scream, feeding on it, blending, changing, anger, incandescent blue anger, raging like the Goddess’s wrath—hands, surely burned off, eyes transfixed by spears of blue-white fury, too much, too much power, has to go somewhere, forward, moments moving, forward, terror, rage, forward, Freelorn—!

—staggering forward, carrying the half-finished sword in his hand, and a murderous freight of rage within him, burning under his skin like the red-hot heart of a coal under its white ash. No anger he had ever summoned had been this potent, it was devouring him from within, he was fire, like Sunspark, ah, Sunspark, loved, gone, dear one!— and he sobbed, his own fires consuming him now, fury, horror,

revenge, he tried to treat them as a sorcery, shaping them, directing them, scorching himself with them, weaving them—

—something stumbled into the firefield he was making, no, that he was, for it was he and he it; that’s the secret, isn’t it—not trying to use a tool, but being one with it—who uses their hand to do something? It does it— Out there, the somethings— or rather, the not-somethings, for they had no names nor any true life— now sensed his sudden incredible upsurge of life, of selfness, and were closing in for such a feed as they had never had in all their centuries. Well, let them try. They are not alive, so it’s all right to kill them—disassemble would be a better word, actually; see, a break here, at this linkage, and here, quite simple; I know what I’m for and they can’t say as much—now the hard part, push—

If Freelorn’s scream had terrified him, the ones that came now were worse, but Herewiss shut them out. He stood still, clenching hard on his sword, on himself, his eyes squeezed shut. Outside of him he perceived a terrible turbulence and upset, a maelstrom of freed forces that shook the air inside his lungs and battered at the thoughts inside his head. But he felt sure that if he looked to see what was happening, something might go wrong. He urged the anger on, feeding it with his fears, pouring it out. It pushed through his pores as if he were sweating molten metal. His skin would have melted too were it not already charred into a blackened shell. The burning had rooted itself deep in him, his bones glowed like iron in the forge. His heart raced, its rhythm staggering in pain, every beat an explosion of sparks and burnt blood. But still he pushed, fanned the fire, breathed it hotter, pushed, pushed—

The hralcins keened and screeched up to the top of the range of hearing, a multiple cry of agony and excruciating fright. The sound hurt the ears, piercing them unbearably, boring inward to the brain—

—and then it stopped.

•

The Book of Night With Moon

The Book of Night With Moon A Wind From the South

A Wind From the South A Wizard Abroad, New Millennium Edition

A Wizard Abroad, New Millennium Edition Lior and the Sea

Lior and the Sea Uptown Local and Other Interventions

Uptown Local and Other Interventions High Wizardry New Millennium Edition

High Wizardry New Millennium Edition Games Wizards Play

Games Wizards Play Wizard's Holiday, New Millennium Edition

Wizard's Holiday, New Millennium Edition So You Want to Be a Wizard, New Millennium Edition

So You Want to Be a Wizard, New Millennium Edition The Door Into Sunset

The Door Into Sunset To Visit the Queen

To Visit the Queen A Wizard Abroad

A Wizard Abroad Not on My Patch

Not on My Patch The Door Into Shadow

The Door Into Shadow The Door Into Fire

The Door Into Fire A Wizard Alone New Millennium Edition

A Wizard Alone New Millennium Edition The Tale of the Five Omnibus

The Tale of the Five Omnibus The Wizard's Dilemma, New Millennium Edition

The Wizard's Dilemma, New Millennium Edition The Big Meow

The Big Meow Wizards at War, New Millennium Edition

Wizards at War, New Millennium Edition Interim Errantry

Interim Errantry Omnitopia: Dawn

Omnitopia: Dawn High Wizardry

High Wizardry Spider-Man: The Venom Factor Omnibus

Spider-Man: The Venom Factor Omnibus Spider-Man: The Venom Factor

Spider-Man: The Venom Factor Seaquest DSV

Seaquest DSV How Lovely Are Thy Branches

How Lovely Are Thy Branches So You Want to Be a Wizard

So You Want to Be a Wizard Midnight Snack and Other Fairy Tales

Midnight Snack and Other Fairy Tales Stealing the Elf-King's Roses

Stealing the Elf-King's Roses Interim Errantry 2: On Ordeal

Interim Errantry 2: On Ordeal Raetian Tales 1: A Wind from the South

Raetian Tales 1: A Wind from the South Starrise at Corrivale h-1

Starrise at Corrivale h-1 The Wizard's Dilemma

The Wizard's Dilemma Sand and Stars

Sand and Stars How Lovely Are Thy Branches: A Young Wizards Christmas

How Lovely Are Thy Branches: A Young Wizards Christmas On Her Majesty's Wizardly Service fw-2

On Her Majesty's Wizardly Service fw-2 X-COM: UFO Defense

X-COM: UFO Defense Star Trek: The Original Series: Rihannsu, Book 5: The Empty Chair

Star Trek: The Original Series: Rihannsu, Book 5: The Empty Chair seaQuest DSV: The Novel

seaQuest DSV: The Novel Stealing the Elf-King's Roses: The Author's Cut

Stealing the Elf-King's Roses: The Author's Cut Not On My Patch: a Young Wizards Hallowe'en Story

Not On My Patch: a Young Wizards Hallowe'en Story A Wizard Alone yw[n&k-6

A Wizard Alone yw[n&k-6 The Bloodwing Voyages

The Bloodwing Voyages Games Wizards Play (Young Wizards Series)

Games Wizards Play (Young Wizards Series) The Book of Night with Moon fw-1

The Book of Night with Moon fw-1 My Enemy My Ally

My Enemy My Ally Dark Mirror

Dark Mirror Star Trek: The Original series: Rihannsu: The Bloodwing Voyages

Star Trek: The Original series: Rihannsu: The Bloodwing Voyages Deep Wizardry yw[n&k-2

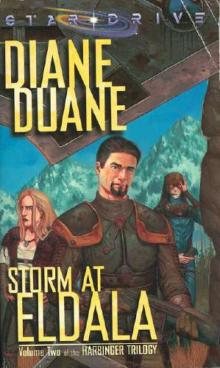

Deep Wizardry yw[n&k-2 Storm at Eldala h-2

Storm at Eldala h-2