- Home

- Diane Duane

The Tale of the Five Omnibus Page 20

The Tale of the Five Omnibus Read online

Page 20

(I thought Freelorn said that it took Flame to open a door.)

“Yes, he did, and he’s probably right, since doors are more or less alive. But this is an unbinding for inanimate objects, and if I make a few changes in the formula, it might work. I have to try something.”

(Will you need me?)

“Just to stand guard.” Herewiss sat down cross-legged against the wall again, breathed deeply and started to compose his mind. It took him a while; his excitement was interfering with his concentration. Finally he achieved the proper state, and turned his eyes downward to read from the grimoire.

“M’herie nai naridh veg baminédrian a phrOi,” he began, concentrating on building an infrastructure of openness and nonrestriction, a house made out of holes. The words were slippery, and the concepts kept trying to become concrete instead of abstract, but Herewiss kept at it, weaving a cage turned inside out, its bars made of winds that sighed and died as he emplaced them. It was both more delicate a sorcery and more dangerous a one than that which he had worked outside of Madeil. There the formulae had been fairly straightforward, and the changes introduced had been quantitative ones rather than the major qualitative shifts he was employing here. But he persevered, and took the last piece away from the sorcery, an act that should have started it functioning.

It sat there and stared at him, and did nothing.

He looked it over, what there “was” of it. It should have worked: it was “complete,” as far as such a word could be applied to such a not-structure. Maybe I didn’t push it hard enough against the door, he thought. Well— He gave it a mighty shove inside his head. It lunged at him and hit him in the back of the inside of his mind, giving him an immediate headache.

Dammit-to-Darkness, what did I—did I put a spin on it somehow? The shift could have done that, I guess. Well, then.

He pulled at it, and immediately it slid toward the doorway and partway through it. There the sorcery came to a halt, and sat twitching. Nothing came out of the door.

Maybe if I wait a moment, Herewiss thought.

He waited. The sorcery stopped twitching and fell into a sullen stillness.

Herewiss lost his temper. (Dark!) he swore, and lashed out at the sorcery, backhanding it across the broad part of the nonstructure instead of disassembling it piece by piece, slowly, as he should have. It fell apart, nothingness collapsing into a higher state of nonexistence—

Something came out the door.

He opened his eyes, and just enough of the Othersight was functioning to give him a horrible dual vision of what was happening. The door itself was still dark to his normal sight; but the Othersight showed him something more tenebrous, more frightening, a hideous murky knotted emptiness, the whole purpose of which was containment and repression. It was a prison. And the prisoner was coming through the door right then: a huge awful bulk that couldn’t possibly be fitting through that door, but was—a botched-looking thing, a horrible haphazard combination of bloated bulk and waving, snatching claws, with an uncolored knobby hide that the filtered afternoon light somehow refused to touch. Herewiss caught a brief frozen glimpse of teeth like knives in a place that should not have been a mouth, but was. Then the Othersight confused itself with his vision again, and he was perceiving the thing as it was, the embodiment of unsatisfied hungers, a thing that would eat a soul any chance it got, and the attached body as an hors d’oeuvre. He underheard a feeling like the taste at the back of the throat after vomiting, a taste like rust and acid.

Through the confusion of perceptions, one thought made itself coldly clear: Well, this is it. I tried, and I did wrong, and now I’m going to pay the price. The sorcery had already backlashed, leaving him wobbly and weak, and he watched helplessly as the thing leaned out of the door over him and examined him, assessing the edibility of his self as an epicure looks over a dinner presented him—

Something grabbed him. Herewiss commended his soul to the Goddess, hoping that it would manage to get to Her in the first place, before he realized that Sunspark had him and was running.

“Where—” he said weakly.

(Anywhere, but out of here! I have seen those things before, at a distance, and there’s no containing them—)

“But it was contained. Spark, what is it?”

(The name I heard applied to it was ‘hralcin.’ If you desire to stay in this body, we must get you away from here quickly. They eat selves—)

“Your kind too?”

(No one knows. None of my people have ever had a confrontation with one of the things, as far as I know, and I would rather not be the first!)

Herewiss realized that Sunspark was still in the human form, running with him down the stairs and into the main hall. Behind them there was a great noise of roaring and crashing.

“Do you think it could kill you?”

(I don’t know. I don’t think so. But I have heard of those things taking souls, and the souls never came back, not that anyone had ever heard in the places where I’ve traveled. They say that one or two hralcins can depopulate a whole world, one soul at a time. We could go through one of the doors until it goes elsewhere—)

“Sunspark, put me down.”

(What??)

“Let me go.”

Sunspark put Herewiss down on the floor of the main hall and turned into a tower of white fire that reached from floor to ceiling. Herewiss wobbled to his feet.

“I don’t know how I managed to call it—”

(You said that the spell you were using was originally for inanimate objects?)

“Yes, but—”

(There’s your answer. The thing’s not alive. Why do you think it eats souls? When it has gotten enough of them, it gains life—)

“We’ve got to get it back in there.”

(You are a madman,) Sunspark said. (There is no containing the things within anything short of a worldwall.)

“But it was contained! If it was in there, and bound, it can be gotten in there again, and rebound—”

(Whoever put it in there knew more about it than we do, certainly. This much I know, hralcins don’t like light much. I can keep it away from us, I think. But it’s only a matter of time until it leaves this place and gets out among your poor fellow creatures—and then there’ll be little time left to them.)

“It mustn’t happen. They don’t like light?”

(No.)

“Maybe we can drive it back in through that doorway. Then I could bind it back in again—”

(But it takes you forever!) Sunspark’s flames were trembling; the crashing was coming down the stairs. (And the thing would make a quick meal of you. It’s got your scent, and once these things smell soul they pursue it until they catch it—)

Herewiss was sucking in great gulps of air, desperately fighting off the backlash. “I can decoy it back into the doorway. It’ll follow me. Then I’ll come out again, and you will hold it in with your fires until I can weave the necessary spell—”

Sunspark looked at Herewiss, a long moment’s regard flavored with unease and amazement. (I can hold it off from you—)

“Sunspark, if that thing can empty whole worlds of people, what will it do to the Kingdoms? Come on. We’ll let it into the hall, and I’ll duck back up behind it, and you drive it up behind me. Then up, and through the door, and you can hold it in—”

(Very well.)

The hralcin came careening down the stairs, all horrible misjointed claws reaching out toward Herewiss as it staggered from the stairwell and across the floor. (I can direct the fire and the light pretty carefully,) Sunspark said, (but try to keep out from in front of me, or else well ahead. I’m going to let go.)

“Right.”

Herewiss stumbled off to Sunspark’s right, and the hralcin immediately changed direction to follow him. At that moment Sunspark went up in a terrible blaze of light and heat, so brilliant that it no longer manifested the appearance of flames at all—it was a fierce eye-hurting pillar of whiteness, like a column carved of light

ning. The hralcin screeched, put up several of its claws to shield what might have been eyes, a circlet of irregular glittering protuberances set in the rounded top of its pear-shaped body. Herewiss dodged around it and scrambled up the stairs, slipping and falling on the slime the thing had left.

At the top of the stairs he paused for just a moment, feeling sick, and his eyes dazzled as his body tried to faint; but he wouldn’t let it. The stench in the hall was terrible, as if the hralcin carried around the rotting corpses of its victims as well as their souls. Herewiss went staggering down past doorway after doorway, and finally found the right one. It was still black, and he quailed at the thought of going in there, maybe being imprisoned there himself, never finding the way out again, and the hralcin coming in after him—

He heard it screaming up the stairs after him. He thought, Lorn, dammit!

He went in.

Immediately darkness closed around him, as if he had crawled back into a womb. There was no smell, no sound, nothing to see; he reached out and could feel nothing at all around him. He turned, looked for the doorway. It was still there, thought hard to see through the murkiness of this other place, and it wavered as if seen through a heat haze.

There was something wrong with his chest. He was breathing, but it was as if there was nothing really there to fill his lungs. Herewiss inched back to the doorway, put his head out to breathe.

The hralcin was coming down the hall, backlit brilliantly by the pursuing Sunspark. It saw Herewiss, screamed, and came faster. Herewiss took a long, long breath, like a swimmer preparing for a plunge. It could be your last, he thought miserably, and ducked back into darkness.

Silence, and the doorway was vague before him again.

Herewiss had a sudden thought. He edged around to the side of the doorway, until he was seeing it only as a very thin wedge of light, and then as a line, like that of a normal door open just a crack. He put his hand gingerly into the place behind the door, where the hallway would have been in the real world.

Nothing, just more darkness.

He slipped around and hid in it, his pulse thundering in his ears, the only thing to be heard.

There was a rippling, a stirring. Right in front of him, hardly a foot from Herewiss’s nose, the hralcin seemed to bloom out from a flat, irregularly-shaped plane into complete and rounded existence. He started back, then watched it blunder further into the darkness; Sunspark’s light washed through the door after it and limned it clearly. Even muted and blurred by the darkness of this other place, Sunspark’s brilliance was still blinding. Herewiss could imagine what the heat must be like. But if it let up for so much as a second, the hralcin would only come out again—

Herewiss ducked out from behind the doorway, his

lungs screaming for air, and threw himself through, diving and rolling. Behind him he could feel the vibrations of the hralcin’s scream through the water-dark space, cut off sharply as he passed through the doorway and crashed to the ground. His face and hands were seared by Sunspark’s fires. He dragged himself behind the elemental, and the burning lessened , though the air in the hall was still like an oven; the stone was reflecting back much of the heat of its flames.

(Are you all right?)

“Not really. But we have to finish this—”

A claw waved out through the doorway, and Sunspark blazed up more fiercely yet. The reflected heat stung Herewiss’s burned face terribly, but the claw and the limb to which it was attached were withdrawn.

(It’s building up a tolerance,) Sunspark said. (Hurry!)

Herewiss found the grimoire half-hidden under a

great glob of slime. He grabbed the book, fumbled at the pages. “I am, I am—”

Another claw came out the door. Sunspark spat a tongue of flame at it, and the claw disappeared. The smell in the hallway became much worse.

Bindings, inanimate—great bindings—they’d better be! Herewiss threatened himself into a semblance of calm, started building the necessary structure around and against the doorway Luckily it was a very simple and straightforward one, requiring more power than delicacy, and his need was fueling his power more than adequately “—e n’sradië!” he finished, sealing it, standing away from the structure in his mind. “All right, Spark, let’s see if it holds.”

Sunspark dimmed down its fires, and the hralcin slammed against the binding thrown over the door as if against a stone wall The binding held, though. Herewiss trembled with the reflected shock.

The hralcin hit the wall again. It still held

And again.

And again.

The wall held.

Herewiss sagged back against the hot stone, regardless of getting burnt. Sunspark was in the man-shape again, helping him.

“My room,” Herewiss said, the backlash hitting him with redoubled force. “I think I need a nap—”

Before Sunspark had gotten him halfway down the stairs, he was having one.

***

He woke up in his bed in the tower workroom, a makeshift affair of cushions and blankets that Sunspark had filched for him from one place or another. It was dark; the room was lit only by the two big candles on the worktable. Herewiss looked up and out the window, seeing early evening stars.

(Well. About time.)

He turned his head to the center of the room. Sunspark was there, enfleshed in the form of a tall slender woman with dark eyes and hair the color of a brilliant sunset, long and red-golden. She sat in a big old padded chair, looking at him with slightly unnerving concern. She was gowned all in wine-red, and her sleeves were rolled up.

“How long has it been?” Herewiss said, propping himself up on one elbow.

(A night and a day.)

“The hralcin—”

(The binding is holding very nicely.) Sunspark got up, went to Herewiss and laid her hand against his forehead; it burned him slightly, but he bore it. (Better,) she said. (Last night there was little difference between the feel of your skin and mine; but the fever is down now. How are the burns?)

“They sting. The skin is tight, but I’ll live, I think.” Herewiss looked around him. There was a big bowl on the floor with a sponge in it, and the dark liquid inside it smelled like burn potion.

“Were you using that on me?”

(Yes. The recipe was in your grimoire, and you had most of the herbs in your supplies—)

“But the water, Spark. I thought you couldn’t touch it—”

(A minor inconvenience, in quantities that small—I

shielded my hand with a cloth, anyway. It makes a feeling like a headache, nothing so terrible. Can you get up and eat?)

My Goddess—it’s, she’s worried about me, she cares—what a wonder! “Spark, thank you—I could eat a Dragon raw.”

(No need, really. I could cook it for you.)

Herewiss sat up straight and stretched. He was stiff from the burns, but not too much so, and the backlash had diminished to the point where he only felt very tired. “Oh. You brought a new chair?”

(From the little town up north where I’ve been getting the food. They’ve started to leave things out for me at night; some of them leave doors and windows open.) She chuckled and got up, going out of the room and down the hall to another room where supplies were kept. (I guess the news got around when their neighbors started finding pantries empty of food and full of raw gold.)

“I would imagine.” Herewiss was surprised at Sunspark’s initiative on his behalf.

(And not far from here there’s a subsurface cavern full of raw gems of all kinds, though mostly rubies. I took the chair and left them a ruby about the size of a melon. Soon the streets will be filling with furniture.)

Sunspark came back in with a few slices of hot venison on a trencher of bread. Under her arm was a skin of Brightwood white, the last of Freelorn’s liberated supply.

“Don’t carry it like that—you’ll warm it up!”

(Oh. Sorry.) She laid the skin on the table with the food, and Herewiss stared at

it morosely as Sunspark went rummaging through his bass to find the lovers’-cup. I wonder where he is, thought Herewiss. Probably stuck in some damn dungeon in Osta, trying to figure out a way to bribe the guards to send me a message…

Sunspark looked at Herewiss as she set the cup on the table and poured the wine. She said nothing.

“I wish he were here,” Herewiss said.

Sunspark shook the skin to get the last few drops out, stoppered it, and put it away. (You would probably quarrel again,) she said.

“How would you know?” Herewiss said, stirred slightly out of his tiredness by anger. “You’re rather new at this sort of thing to be so understanding of it, don’t you think?”

(Some aspects of it,) Sunspark answered without rancor. (But some are much like the ways of my own people. There are still more likenesses between our kinds than differences, I think.)

“So what are you basing your feeling on, that we would quarrel again?”

Sunspark sat down among the cushions, hesitated . (He’s seeking to bind your energies, that one is,) she said.

“As I bound yours? Ridiculous. He’s my loved.”

(But that is a binding. Your loved, you said. It’s not the same kind of binding as there is between us, true. But you have—commitments, you have set ways in which you treat one another—)

Herewiss remembered the terrible alienness of the last night with Freelorn, the feeling of having a stranger in the bed—all the more terrible because the stranger had been his loved not half an hour before. “The way he treated me is nothing I ever saw before.”

(Well enough. But when one form of binding doesn’t work, an entity tries another—)

Dully, Herewiss began to eat. The food seemed tasteless. “And he was doing that?”

(It could be. Your strength is considerable, though. It comes as no surprise that he went away so angry. I think he’ll try again, but not the way he did last time—)

“It seems so useless. I need my Power—I thought he understood that—”

(The little one, the shieldmaid,) Sunspark said, (she understands. I think he might envy that a little.)

The Book of Night With Moon

The Book of Night With Moon A Wind From the South

A Wind From the South A Wizard Abroad, New Millennium Edition

A Wizard Abroad, New Millennium Edition Lior and the Sea

Lior and the Sea Uptown Local and Other Interventions

Uptown Local and Other Interventions High Wizardry New Millennium Edition

High Wizardry New Millennium Edition Games Wizards Play

Games Wizards Play Wizard's Holiday, New Millennium Edition

Wizard's Holiday, New Millennium Edition So You Want to Be a Wizard, New Millennium Edition

So You Want to Be a Wizard, New Millennium Edition The Door Into Sunset

The Door Into Sunset To Visit the Queen

To Visit the Queen A Wizard Abroad

A Wizard Abroad Not on My Patch

Not on My Patch The Door Into Shadow

The Door Into Shadow The Door Into Fire

The Door Into Fire A Wizard Alone New Millennium Edition

A Wizard Alone New Millennium Edition The Tale of the Five Omnibus

The Tale of the Five Omnibus The Wizard's Dilemma, New Millennium Edition

The Wizard's Dilemma, New Millennium Edition The Big Meow

The Big Meow Wizards at War, New Millennium Edition

Wizards at War, New Millennium Edition Interim Errantry

Interim Errantry Omnitopia: Dawn

Omnitopia: Dawn High Wizardry

High Wizardry Spider-Man: The Venom Factor Omnibus

Spider-Man: The Venom Factor Omnibus Spider-Man: The Venom Factor

Spider-Man: The Venom Factor Seaquest DSV

Seaquest DSV How Lovely Are Thy Branches

How Lovely Are Thy Branches So You Want to Be a Wizard

So You Want to Be a Wizard Midnight Snack and Other Fairy Tales

Midnight Snack and Other Fairy Tales Stealing the Elf-King's Roses

Stealing the Elf-King's Roses Interim Errantry 2: On Ordeal

Interim Errantry 2: On Ordeal Raetian Tales 1: A Wind from the South

Raetian Tales 1: A Wind from the South Starrise at Corrivale h-1

Starrise at Corrivale h-1 The Wizard's Dilemma

The Wizard's Dilemma Sand and Stars

Sand and Stars How Lovely Are Thy Branches: A Young Wizards Christmas

How Lovely Are Thy Branches: A Young Wizards Christmas On Her Majesty's Wizardly Service fw-2

On Her Majesty's Wizardly Service fw-2 X-COM: UFO Defense

X-COM: UFO Defense Star Trek: The Original Series: Rihannsu, Book 5: The Empty Chair

Star Trek: The Original Series: Rihannsu, Book 5: The Empty Chair seaQuest DSV: The Novel

seaQuest DSV: The Novel Stealing the Elf-King's Roses: The Author's Cut

Stealing the Elf-King's Roses: The Author's Cut Not On My Patch: a Young Wizards Hallowe'en Story

Not On My Patch: a Young Wizards Hallowe'en Story A Wizard Alone yw[n&k-6

A Wizard Alone yw[n&k-6 The Bloodwing Voyages

The Bloodwing Voyages Games Wizards Play (Young Wizards Series)

Games Wizards Play (Young Wizards Series) The Book of Night with Moon fw-1

The Book of Night with Moon fw-1 My Enemy My Ally

My Enemy My Ally Dark Mirror

Dark Mirror Star Trek: The Original series: Rihannsu: The Bloodwing Voyages

Star Trek: The Original series: Rihannsu: The Bloodwing Voyages Deep Wizardry yw[n&k-2

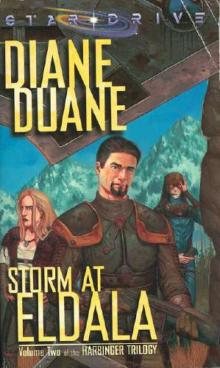

Deep Wizardry yw[n&k-2 Storm at Eldala h-2

Storm at Eldala h-2