- Home

- Diane Duane

On Her Majesty's Wizardly Service fw-2 Page 2

On Her Majesty's Wizardly Service fw-2 Read online

Page 2

ONE

At just before 5:00 p.m. on a weekday, the upper track level of Grand Central Terminal looks much as it does at any other time of day: a striped gray landscape of long concrete islands stretching away from you into a dry, iron-smelling night, under the relentless fluorescent glow of the long lines of overhead lighting. Much of the view across the landscape will be occluded by the nine Metro-North trains whose business it is to be there at that time, and by the rush and flow of commuters through the many doors leading from the echoing Main Concourse to the twelve accessible platforms’ near ends. The commuters’ thousands of voices on the platforms and out in the Concourse mingle into a restless undecipherable roar, above which the amplified voice of the station announcer desperately attempts to rise, reciting the cyclic poetry of the hour: ” … now boarding, the five oh two departure of Metro-North train number nine five three, stopping at One Hundred and Twenty-Fifth Street, Scarsdale, Hartsdale, White Plains, North White Plains, Valhalla, Hawthorne, Pleasantville, Giappaqua …” And over it all, effortlessly drowning everything out, comes the massive basso B-flat bong of the Accurist clock, echoing out there under the blue-painted backwards heaven, two hundred feet above the terrazzo floor.

Down on the tracks, even that huge note falls somewhat muted, having as it does to fight with the more immediate roar and thunder of the electric diesel locomotives, clearing their throats and getting ready to go. By now Rhiow knew them all better than any trainspotter, knew every engine by name and voice and (in a few specialized cases) by temperament … for she saw them every day in the line of work. Right now they were all behaving themselves, which was just as well: she had other work in hand. It was no work that any of the other users of the Terminal would have noticed—not that the rushing commuters would in any case have paid much attention to a small black cat, a patchy-black-and-white one, and a big gray tabby sitting down in the relative dimness at the near end of Adams Platform … even if the cats hadn’t been invisible.

Bong, said the clock again. Rhiow sighed and looked up at the elliptical multicolored shimmer of the worldgate matrix which hung in the air before them, the colors that presently ran through its warp and woof indicating a waiting state, no patency, no pending transits. Normally this particular gate resided between tracks Twenty-Three and Twenty-Four at the end of Platform K; but for today’s session they had untied the hyperstrings holding it in that spot, and relocated the gate temporarily on Adams Platform. This lay between the Waldorf Yard and the Back Yard, away off to the right of Tower C, the engine inspection pit, and the power substation: it was the easternmost platform on the upper level, and well away from the routine trains and the commuters … though not from their noise. Rhiow glanced over at big gray tabby Urruah, her colleague of several years now, who was flicking his ears in irritation every few seconds at the racket. Rhiow felt like doing the same: this was her least favorite time to be here. Nevertheless, work sometimes made it necessary. Bong, said the clock: and clearly audible through it, through the voices and the diesel thunder and the sound of the slightly desperate-sounding train announcer, a small clear voice spoke. “These endless dumb drills,” it said, “lick butt.”

WHAM!—and Arhu fell over on the platform, while above him Urruah leaned down, one paw still raised, wearing an expression that was surprisingly mild—for the moment. “Language,” he said.

“Whaddaya mean?! There’s no one here but you and Rhiow, and you use worse stuff than that all the—”

WHAM! Arhu fell over again. “Courtesy,” Urruah said, “is an important commodity among wizards, especially wizards working together as a team. Not to mention mere ordinary people working as teams or in-pride, as you’ll find if you survive that long. Which seems unlikely at the moment. My language isn’t at question here, and even if it were, I don’t use it on my fellow team members, or to them, even by implication.”

“But I only said—” Arhu suddenly fell silent again at the sight of that upraised paw.

Dumb drills, Rhiow thought, and breathed out, resigned. This is not a drill, life is not a drill, when will he get the message? Lives … She sighed again. Sometimes I think the One made a mistake telling our people that we’re going to get nine of them. Some of us get complacent…

“Let’s be clear about this,” Urruah said. “Our job is to keep the worldgates down here functioning. Human wizards can’t do this kind of work, or not nearly as well as we can, anyway, since we can see hyperstrings, and ehhif can’t without really working at it. That being the case, the Powers That Be asked us very politely if we would do this job, and we said yes. You said yes, too, when They offered you wizardry and you took it, and you said “yes” again when we took you in-pride and you agreed to stay with us. That means you’re stuck with the job. So you may as well learn how to do it right, and part of that involves working smoothly with your teammates. Another part of it is practicing managing these gates until you can do it quickly, in crisis situations, without having to stop to think and worry and “figure out” what you’re doing. And this is what we are teaching you to do, and will continue teaching you to do, until you can exhibit at least a modicum of effectiveness, which may be several lives on, not that it matters to me. You got that?”

“Uh huh.”

“Uh huh what?”

“Uh huh, I got it.”

“Right. So let’s start in again from the top.”

Rhiow sighed and licked her nose as the small black-and-white cat sat up on his haunches again and thrust his forepaws into the faintly glowing warp and woof of the worldgate’s control matrix, and muttered under his breath, very softly, “It still licks butt.”

WHAM!

Rhiow closed her eyes and wondered where she and Urruah would ever find enough patience for this job. Inside her, some annoyed part of her mind was mocking the Meditation. I will meet the terminally clueless today, it said piously: idiots, and those with hairballs for brains, and those whose ears need a good shredding before you can even get their attention. I do not have to be like them, even though I would dearly love to hit them hard enough to make the empty places in their heads echo…

She turned away from that line of thought in mild annoyance at herself as Arhu picked himself up off the platform one more time. This late on in this life, Rhiow had not anticipated being thrust into the role of nursing-dam for a youngster barely finished losing his milk teeth … and certainly not into the role of the trainer of a new-made wizard. She had gained her own wizardry in a different paradigm—acquiring it solo, and not becoming part of a team until she had proven herself expert enough to survive past the first flush of power. Arhu, though, had broken the rules, coming to them halfway through his Ordeal and dragging them all through it with him. He was still breaking every rule he could find, having apparently decided that since the tactic worked once, it would probably keep on working.

Urruah, however, was slowly breaking him of this idea … though getting anything through that resilient young skull was plainly going to take a while. Urruah, too, was playing out of role. Here he was, the very emblem of hardy individuality and independence, a big muscular broad-striped torn, all balls and swagger, wearing the cachet of his few well-placed scars with an insouciant, good-natured air—but now he leaned over the kitten-becoming-cat which the Powers had wished upon them, and acted very much the hard-pawed pride-father. It was a job to which Urruah had taken with entirely too much relish, Rhiow thought privately, and she was at pains never to mention to him how much he seemed to be enjoying the responsibility. Does he see himself in this youngster, Rhiow thought, … does he see the wizard he might have been if he’d had this kind of supervision? But then, who among us wouldn’t see ourselves in him? The way you feel your way along among the uncertainties—and the way you try to push your paw just a little further through the hole, trying to get at what’s squeaking on the other side. Even if it bites you…

Arhu had picked himself up one more time, with no further mutters, and was putting his paws in

to the glowing weave again. You have to give him that, Rhiow thought: he always gets back up. “I’ve given the gate some parameters to work with already, though I’m not going to tell you what they are,” Urruah said. “I want you to find locations that match the parameters, and open the gate for visual patency, not physical.”

“Why not? If I can—”

“Visual-only is harder,” Rhiow said. “Physical patency is easy, when you’re using a pre-established gate: anyway, in a lot of them, the physical opening mechanism has become automated over time. Restricting the patency, refining control … that’s what we’re after, here.”

Arhu started hooking the control strings with his claws, slowly pulling each one out with care—which was as well: the gates were nearly alive, in some ways, and if misused or maltreated, they could bite. “I wish Saash was here,” Arhu muttered. “She was better at explaining this …”

“Than we are? Almost certainly,” Rhiow said. “And I wish she was here too, but she’s not.” Their friend and fellow team-member Saash had passed through and beyond her ninth life within the past couple of months, under unusual circumstances: though none of our circumstances have actually been terribly usual lately, Rhiow thought with some resignation. They all missed Saash in her role as gating technician, where her expertise at handling the matrices had come shining through her various mild neuroses with unusual brilliance. But Rhiow found herself just as lonely for her old partner’s rather acerbic tongue, and even for her endless scratching, the often-misread symptom of a soul long grown too large for the body that held it.

“Saash,” Urruah said to Arhu, “knowing her, is probably explaining to Queen Iau that she thinks the entire structure of physical reality needs a serious reweave: so you’d better get on with this before she talks the One into it, and the Universe dissolves out from under us. Quit your complaining and pick up where you left off.”

“I can’t figure out where that is! It’s not the way I left it, now.”

“That’s because it’s returned to its default configuration,” Urruah said, “while you were recovering from sassing me.”

“Start from the beginning,” Rhiow said. “And just thank the Queen that gate structures are as robust as they are, and as forgiving: because those qualities are likely to save your pelt more than once, in this business.”

Arhu sat there, narrow-eyed, with his ears back. “Two choices,” Urruah said, after a moment. “You can sulk and I can hit you, or you can get on with your work with your ears unshredded. Look at you, sitting here wasting all this perfectly good gating time.”

Arhu glanced back down the station at the other platforms, which were boiling with ehhif commuters rushing up and down and in some cases nearly pushing one another onto the tracks. “Doesn’t look perfect to me. I know we’re sidled, but what if one of them sees what we’re doing?”

There won’t be much for them to see at the rate you’re going,” Urruah said.

“Ehhif don’t see wizardry half the time, even when it’s hanging right in front of their weak little noses,” Rhiow said. “The odds against having anyone notice anything, down here in the dark and the noise, are well in your favor—if you ever get on with it. If you’re really all that concerned, rotate the gate matrix a hundred and eighty degrees and specify one-side-only visual patency. But I don’t think you need to bother. These are New Yorkers, and no trains of interest to them are due on these side tracks, so for all that it matters, we and the gate and this whole side of the station might as well be on the Moon.”

“Not a bad idea,” Arhu muttered, putting his whiskers forward in the slightest smile, and reached more deeply into the weft of the gate matrix.

He fell over backwards as Urruah clouted him upside the head. “No gatings into vacuum,” he said. “Or under water, or below ground level, or into any other environment which would be bad if mixed freely with this one.”

Arhu got to his feet, shook himself and glared at Urruah. “Aw, I was just thinking …”

“Yes, and I heard you. No off-planet work for you until you’re better with handling the structural spells for these gates.”

“But other wizards can just get the spell from their manuals, or the Whispering, or whatever way they access wizardry, and go—”

“You’re not ‘other wizards’,” Rhiow said, pacing over to sit down beside Urruah as a more obvious gesture of support. “You are part of a gating team. You have to understand the theory and nature of these structures from the bottom up. And as regards the established gates like this one, you’ve got to be able to fix them when they break—take them apart and put them back together again—not just use them for rapid transit like “other wizards”. Yes, it’s specialized work, and the details are a nuisance to learn. And yes, the structure is incredibly complex: Aaurh Herself made the gates, Iau only knows how long ago -what do you expect? But you’ve got to know this information from the inside, without having to consult the Whisperer every thirty seconds for advice. What if She’s busy?”

“How busy can gods get?” Arhu muttered, turning his attention back to the gate.

“You’d be surprised,” Urruah said. “Queen Iau’s daughters have their own lives to lead. You think the Silent One has all day to sit around waiting to see if you need help? Get off those little thaith of yours and do something.”

“They’re not little,” Arhu said, and then fell silent for a moment. ” … All right, should I just collapse this and start over?”

“Sure, go ahead,” Rhiow said.

Arhu reached out a paw and hooked one claw into one of the glowing control strings of the gate. The visible gate-locus vanished, leaving nothing behind it but the intricate, faint traces of hyperstring structure in the air.

And he’s right about them not being little, Rhiow said privately, from her mind to Urruah’s.

When even you notice that, oh spayed one, Urruah said, it suggests that we may shortly have a problem on our hands.

Rhiow stifled a laugh, keeping her eye on Arhu as he studied the gate matrix, then sat up again and started slowly hooking strings out of the air to “reweave’ the visible matrix. It surprises me that you would describe the concept of approaching sexual maturity as a problem.

Oh, it’s not, not as his affects me anyway, Urruah said. We’re in-pride now: he’s safe with me—it helps that the relationship between you and me isn’t physical. Though I do feel sorry for you, Urruah said, magnanimously.

Rhiow simply put her whiskers forward and accepted the implied compliment without comment. But for him, Urruah said, there’s likely to be trouble coming. Hormonal surges don’t sort well with the normal flow of wizardly practice.

I’m not sure there’s going to be anything normal about his practice for a while, Rhiow said, dry, as they watched the structure of the gate reassert itself in the air, rippling and flowing, wrinkling as if someone was pulling it out of shape from the edges. Arhu had not actually started his task on the gate yet, but he was thinking about it, and the gates were susceptible to the thoughts of the technicians who worked with them.

“Uh,” Arhu said.

“Don’t just pull it in all directions like a dead rat, for Iau’s sake,” Rhiow said, trying not to sound as impatient as she felt. “Take time to get your visualization sorted out first.”

“Remember what I told you about visualizing the entire interweave of the gate’s string structure as organized into five-stranded structures and groups of five,” Urruah said. “Simplest that way: there are five major groupings of forces involved in worldgates, and besides, we have five claws on each paw, and these things are never accidental—”

“Wait a minute,” Arhu said, sitting back again, but with a slightly suspicious look this time. “Are you trying to tell me that the whole species of People was built the way we are just so that we could be gate technicians—?”

“Maybe not just for that purpose, no. But don’t you find it a little strange that we’re perfectly set up to handle strings physi

cally, and that we can see them naturally, when no other species can?”

“The saurians can.”

“That’s a recent development,” Rhiow said wearily. It was one of many “recent developments” which they were all slowly digesting. “Never mind that for now. No other species could. Meantime, do something before the thing defaults again …”

“All right,” Arhu said. “Group one is for phase relationships.” He plucked that control string out as he named it, held it hooked behind one claw, and a series of strings in the matrix ran bright golden as he activated them. Two is for the main hyperstring “junction weave” to four-dimensional space, and the “emphatic” forces: three is for the fifth-dimensional interweave, four is for dimensions six through ten and the lower electromagnetic spectrum, five is for the upper electromagnetic and the strong- and weak-force plena. And then—” He paused, licked his nose.

“Then comes motion,” Urruah said, “—field nutation, sideslip, tesseral, cistemporal, cishyperspatial.” He paused as Arhu leaned in to bite the strings that he was having trouble managing with his paws, “—and then the five strictly physical fields of motion. The planet rotates, it’s inclined on its axis and precesses, it’s also describing a large ellipse around the Sun, and the Sun is moving on the inward leg of a hyperbola with the galactic core at one focus, and the Galaxy—”

The Book of Night With Moon

The Book of Night With Moon A Wind From the South

A Wind From the South A Wizard Abroad, New Millennium Edition

A Wizard Abroad, New Millennium Edition Lior and the Sea

Lior and the Sea Uptown Local and Other Interventions

Uptown Local and Other Interventions High Wizardry New Millennium Edition

High Wizardry New Millennium Edition Games Wizards Play

Games Wizards Play Wizard's Holiday, New Millennium Edition

Wizard's Holiday, New Millennium Edition So You Want to Be a Wizard, New Millennium Edition

So You Want to Be a Wizard, New Millennium Edition The Door Into Sunset

The Door Into Sunset To Visit the Queen

To Visit the Queen A Wizard Abroad

A Wizard Abroad Not on My Patch

Not on My Patch The Door Into Shadow

The Door Into Shadow The Door Into Fire

The Door Into Fire A Wizard Alone New Millennium Edition

A Wizard Alone New Millennium Edition The Tale of the Five Omnibus

The Tale of the Five Omnibus The Wizard's Dilemma, New Millennium Edition

The Wizard's Dilemma, New Millennium Edition The Big Meow

The Big Meow Wizards at War, New Millennium Edition

Wizards at War, New Millennium Edition Interim Errantry

Interim Errantry Omnitopia: Dawn

Omnitopia: Dawn High Wizardry

High Wizardry Spider-Man: The Venom Factor Omnibus

Spider-Man: The Venom Factor Omnibus Spider-Man: The Venom Factor

Spider-Man: The Venom Factor Seaquest DSV

Seaquest DSV How Lovely Are Thy Branches

How Lovely Are Thy Branches So You Want to Be a Wizard

So You Want to Be a Wizard Midnight Snack and Other Fairy Tales

Midnight Snack and Other Fairy Tales Stealing the Elf-King's Roses

Stealing the Elf-King's Roses Interim Errantry 2: On Ordeal

Interim Errantry 2: On Ordeal Raetian Tales 1: A Wind from the South

Raetian Tales 1: A Wind from the South Starrise at Corrivale h-1

Starrise at Corrivale h-1 The Wizard's Dilemma

The Wizard's Dilemma Sand and Stars

Sand and Stars How Lovely Are Thy Branches: A Young Wizards Christmas

How Lovely Are Thy Branches: A Young Wizards Christmas On Her Majesty's Wizardly Service fw-2

On Her Majesty's Wizardly Service fw-2 X-COM: UFO Defense

X-COM: UFO Defense Star Trek: The Original Series: Rihannsu, Book 5: The Empty Chair

Star Trek: The Original Series: Rihannsu, Book 5: The Empty Chair seaQuest DSV: The Novel

seaQuest DSV: The Novel Stealing the Elf-King's Roses: The Author's Cut

Stealing the Elf-King's Roses: The Author's Cut Not On My Patch: a Young Wizards Hallowe'en Story

Not On My Patch: a Young Wizards Hallowe'en Story A Wizard Alone yw[n&k-6

A Wizard Alone yw[n&k-6 The Bloodwing Voyages

The Bloodwing Voyages Games Wizards Play (Young Wizards Series)

Games Wizards Play (Young Wizards Series) The Book of Night with Moon fw-1

The Book of Night with Moon fw-1 My Enemy My Ally

My Enemy My Ally Dark Mirror

Dark Mirror Star Trek: The Original series: Rihannsu: The Bloodwing Voyages

Star Trek: The Original series: Rihannsu: The Bloodwing Voyages Deep Wizardry yw[n&k-2

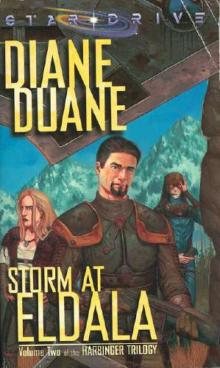

Deep Wizardry yw[n&k-2 Storm at Eldala h-2

Storm at Eldala h-2