- Home

- Diane Duane

Stealing the Elf-King's Roses: The Author's Cut Page 2

Stealing the Elf-King's Roses: The Author's Cut Read online

Page 2

Even now he tried not to hear the word, to see the image. But Lee saw it as Justice, looking through her, did. She felt the Balance inside Blair shift with a groan—the soul admitting itself, in the unavoidable hot glare of Justice’s regard, to have been found wanting, and weighing the scales hard down.

The first sound came from someone on the jury, the kind of angry gasp a man might make when he’s cut himself. Then came another, someone wishing they could deny what they saw, and unable to. If only one juror failed to see what both the prosecution and Justice saw, the judgment would not take.

One last soft moan came from the jury box. Lee didn’t see who it was, but she felt the mind behind the moan make the verdict unanimous. The Power in the room with them struck through her and Alan like lightning; and the nest of unseen swords rose up, surrounded Blair, and sliced him through.

Blair didn’t have a throat for long enough to finish his scream—not a human throat, anyway. The “containment area” in the well, defined by the two meter wide, dull-red square outline of forcefield on the floor, activated with the administration of the sentence. And in the middle of the square, crouching, stunned, was a weasel. It was a very large weasel, for though Justice might affect the soul in a body, and that body’s shape, it had no effect on mass. Clenching its claws against the floor, staring around at its counsel, at Lee, at the magistrate and the jury, the weasel began to make a small, terrible rough sound in its throat, over and over, like a whispered screech.

The pressure of the Regard was gone, vanished like a dream or a nightmare. A lot of people sat down, shocked, but more kept standing, to see better. Lee and Alan both staggered, released, and made their way back to their tables.

Mr. Redpath looked down over his desk at the containment area. “Guilty as charged,” said Mr. Redpath. “Defendant will retain this semblance during the pleasure of inward and outward Justice, here manifested. Upon the end of sentence, the court will be informed whether the defendant desires the optional restitutory stage. Otherwise, here and until the end of sentence, Justice is served.”

The courtroom was very quiet now, that initial rustle of shock and horror having died away. Lee was still blinking hard and trying to get her normal, unaugmented vision back. Boy, she thought, some of the sketch artists in here are going to have a field day with this verdict.

“Your Honor,” said Blair’s counsel, “we desire to lodge an appeal at once, on the grounds that the sentence is excessively severe.”

Mr. Redpath looked down again into the containment area, where the weasel was now trying to sit up on its haunches, and failing. It came down hard on its forefeet again, staring at the long delicate claws and breathing fast. “I so allow. See the court clerk for scheduling. However, Mr. Hess,” said Mr. Redpath, looking down at him rather dryly, “I think the verdict’s severity is secondary to your client having perjured himself. You may want to take advice from your client’s family to discover whether they really want to proceed.”

“Yes, Your Honor,” said Hess, looking glum.

“Then I declare this proceeding to be complete, and I adjourn it sine die,” Mr. Redpath said, and banged his gavel on the desk. “Open the doors; and thank you, ladies and gentlemen.” He got up and headed for his chamber, shrugging his gown back into kilter as he went.

“Please clear the court for the next proceeding,” the bailiff shouted, and people started to file out. In the middle of the courtroom, a uniformed security officer arrived with a large wheeled protective carrier, and there followed an unfortunately humorous interlude while the court security staff tried to get the weasel, presently flinging itself against the walls of the containment area, into the carrier and out of the court.

Lee had been bracing herself against their table. Now Gelert came up beside her and put his cold nose against her neck. “Stop that,” she said, and pushed his snout away, not half as hard as she would have under less casual circumstances, or if she’d had the strength. She wobbled.

“You need the retiring room?” he said privately, implant to implant.

Lee shook her head, still trying to get her breath back. She would pay the price tonight, in sleep, when the reaction set in and her dreams reflected that inexorable gaze concentrating, not on Blair, but on her. Tomorrow, abashed and sore with yet another reminder of her own many failings, she’d ache all over and not be good for much. But the price was worth paying.

From the other side of the aisle came the shuffle and snap of paperwork and a laptop being put away. She glanced over at Hess, stood up straight as her breathing got back to normal, and reflected that at least she wasn’t the only one here who looked completely wrecked. Alan was pale under his tan, and the resultant color made him look very unwell. But “Nice one, Lee,” said Hess to her, polite as always, despite the circumstances.

Lee nodded to him. “Thanks, Al. Look, you did good work, too…Good luck with the appeal.”

He nodded back, went out. “Give me five minutes for the ladies’ room,” Lee said to Gelert.

It was closer to ten, for Lee’s mascara was nowhere near as waterproof as the manufacturer claimed. But the repairs would suffice for the waiting cameras. She slipped out of her silks with a sigh of relief, took off her chain, folded the silks around it, and stowed everything in her briefcase.

Shortly Lee was out in the echoing glass-and-terrazzo main hall again, where Gelert awaited her, and together they went out through the glass doors into the blinding light of a ferocious afternoon, the temperature now pushing above a hundred. The Santa Ana wind was up, blowing so fiercely that the palm trees around New Parker Plaza were bending in the force of it, and the featherduster tops hissed and rattled, each individual frond glinting as if wet in the harsh bright sun. Dust flew everywhere. Lee winced a little at the light but could do nothing about it for the moment; for here were the newsies already, two cameras and a few print people, waiting on the courthouse steps to take a statement from them.

“Good afternoon, folks,” Gelert said amiably, sitting down on the top step.

Lee, pausing beside him, sneezed. “Afternoon, all,” she said. “Please forgive me, it’s the dust…”

“Do you have a prepared statement?” said one of the waiting reporters, not one of the familiar ones. Lee thought she was possibly from Variety or the Reporter.

“No,” Lee said. “We thought we’d just adlib today.”

Gelert sneezed too. “Sorry,” he said. “Can everybody hear me okay? My implant speaker’s been acting up lately when the volume’s turned up out in the open.”

“No problem,” said the Variety reporter, and the others shook their heads.

“Right,” said a third reporter, a little, casually dressed man with dimples and a deceptively innocent face. “Ms. Enfield, this has been the sixth high profile case your firm has been assigned to in the last four months. How do you answer the charge that the DA’s Office is showing favoritism to you because of your former relationship with—”

“If it was a charge,” Lee said, interrupting him and doing her best to keep her smile casual, “I’d suggest that the person making it should look at the results in the cases involved. Our firm appears to produce results, as this is our fifth win out of those six cases. If we’re favorites with the DA’s Office at the moment, it seems we’re favorites with Justice as well…and there’s no way to buy or influence that. Unless you’ve found one?” She gave the reporter what she hoped would pass for an amused look.

“The Ellay District Attorney’s Office assigns cases to the pool of qualified prosecuting teams on an availability basis,” Gelert said, “as you can confirm by checking the court calendar. Our last five cases have been assigned us because in each case we’d just finished another proceeding, and were available. The luck of the draw. But it helps to know what to do with luck.”

A mutter as some of the reporters paused to take notes. “What message would you send to Mr. Blair’s wife and children?” said another.

“That Mr. Blai

r, like every other defendant,” Lee said, “has himself chosen the form of his punishment And that we, like his family, look forward to the day when the Justice living inside him, as it lives inside everyone, decides that he’s served his sentence and can go free. He, and Justice, will work that out for themselves.”

Another mutter from the reporters. “The case is going to appeal,” said another one.

“That’s right,” Gelert said. “And we wish the defendant well; while also suggesting that in this result, Justice has prevailed. But then it always does.”

“Dr. Gelert,” said another reporter, a small trim woman with long blond hair tied back, “what’s your reaction to the statement made by one of your people recently that direct judicial intervention is a ‘blunt instrument’ in this time of increased understanding of criminal motivation?”

Gelert dropped that big fringed jaw and showed many more of his teeth than Lee thought strictly necessary. “‘Cruel and unusual punishment’ again?” Gelert said. “How can Justice’s own self be cruel? And if it’s unusual, that’s our fault, not Its. ‘Hers,’ if you prefer to see Justice that way; lots of humans do. My people, too, actually.” A gust of wind blew a great swirl of dust across the entrance of the courthouse, Lee sneezed, and so did several of the reporters. Gelert shook himself all over, and his chain rang softly. “My people,” Gelert added, “have no crime. No murder, no assault, no theft, nothing of the kind. Certainly no fraud. It colors some of our opinions about the judicial system here. Me, I’ll wait until Councillor Dynef’s been mugged for his earrings some night, coming home from the movies in Westwood. After he’s needed to go through the courts himself, we’ll see how ‘blunt’ he thinks the Hoodwinked Lady’s sword is.”

There was some chuckling at that. “Anything else, ladies and gentlemen?” Lee said. “We’ve got places to be.”

Heads were shaken. “Thanks, then,” Lee said, and she and Gelert turned away. The reporters went off down the stairs.

Lee sneezed again. “Places to be,” Gelert said softly. “What a fibber you are.”

“Huh.” Lee paused to open her briefcase and rummage around in it for her sunglasses. “They keep asking about that,” she muttered. “Why can’t they just let it drop?”

“What? The DA’s Office? Because they’re newsies, as a result of their moms putting scandal in their baby bottles instead of milk. Because it’s obvious, and some of them are only good at obvious.”

Lee sighed. “Yeah, but all they have to do is check the facts to find out—”

“Lee, if it was facts they were after, they wouldn’t be on the courthouse steps. They would have been inside. That guy from the Times, he’s just after evidence to support his pet theory. When he can’t find any, he’ll stop bothering us.”

She found the sunglasses, then put them on and made a face. “Yeah, okay, you’re right,” she said. “It’s just this wind getting to me, I guess…”

“So come on, let’s get out of it,” Gelert said. “Let’s go eat. I’ve got a table booked.”

“Absolutely. Where?’

“Perdu.”

She blinked at him. “What, New York? For lunch? We’re late for that already. And anyway, nobody could get a booking at that place on the same day they call!”

“I reserved it a week ago. And not lunch. Dinner. If we get our tails up to the port instead of standing here chewing over the dry bones, we’ll be just in time for seven thirty.”

“How did you—Gel,” Lee said, “sometimes I think you’re holding out on me. You’re a forward clairvoyant, and you’ve never bothered to register.”

“Too much paperwork,” Gelert said, as they headed for the Metro. “And all clairvoyants get a squint. I refuse to ruin my youthful good looks.”

“Then again, maybe you’re just delusional,” Lee said. “You think you’re a millionaire, all of a sudden, to drop the price of a transcontinental jump for a dinner?”

“We deserve it,” Gelert said, and grinned with all those teeth. “Besides, I dumped a bunch of Oklahoma munis over the weekend and scored thirty percent on the deal. If I keep the money, it’ll only burn a hole in my pocket.”

“What pocket?!”

“Pedant. Come on, or they’ll give away our table.”

*

Two hours later, when Lee glanced up from her fondue and suddenly noticed the King of all the Elves sitting across the room, perusing the wine list, it came as a surprise, but not a huge one—an amusing end to a long day. After all, Le Chalet Perdu was (very quietly) one of the best restaurants in Manhattan. Given the Elf-King’s reputation, and the restaurant’s, sooner or later someone was bound to have brought the two together in an attempt to impress each with the other. And here the Elf-King sat, in a dark blazer and tie and charcoal twills, surrounded by calm-voiced men in Cardin or Botany double-breasted suits—men wearing their mature assurance, or their smoldering youthful cleverness, as if they were weapons. Lee looked away after a first glance, much amused by their talk of wines and entrees. To someone with her training, the lighthearted conversation across the room had a distinct sound of nervous saber rattling. She turned her attention back to her meal. “Gel,” she said, holding out his fondue fork to him, “you smell anything interesting?”

Gelert nipped the cheese-dipped bread cube off the fork, chewed, swallowed, and paused long enough to put his tongue out and lick an escaped blob of Emmenthaler off his whiskers. “Too much nutmeg,” he said, “not enough kirsch.”

“In Konni‘s fondue? Hardly. Something else.”

Gelert’s nose twitched. “Elves.”

“Huh-uh. Elf. The Elf. Laurin.”

Her partner’s pink ears went straight up. “Really. Thought he was supposed to be in The Hague for that conference.”

“Maybe he’s on his way,” Lee said. She speared a chunk of bread for herself, dunked it, waved it in the air, munched. “There isn’t too much nutmeg, either.”

“I was kidding, Lee.” Gelert paused and ducked his head to lap at his bowl of Perrier. “Who else is he with?”

“I don’t recognize any of them. Not that I’d have reason to. We could ask Konni.”

“Right.” Gelert busied himself with finishing his drink. Lee took the opportunity to steal another glance at the table by the far wall. Le Chalet was a small place, done in cream-pale stucco and warmly, brightly lit, so that there was no trouble seeing. The slim, dark man in the elegantly understated jacket and tie put the wine list aside with a gesture that would have been much too graceful, if not for the thoughtless strength inherent in it. Then, all courtesy and attention, he settled down to listen to one of his dinner companions’ remarks about business.

Yet there was something else going on over there. Lee dipped another cube of bread, watching it. The three other well-dressed men, for all their apparent casualness, looked stiff and strained. Their ease was artificial, applied. And the quiet-eyed man who listened to them, though physically alert and erect enough, at the same time seemed inwardly to be lounging— watching their nervousness from a carefully maintained distance, aloof and ever so faintly amused. It was a look that Lee had seen before in Elves. Hell, she thought, everybody’s seen it. It’s one of the ways you tell an Elf in the first place. But in this Elf, the Elf, the effect was both more subtle and more concentrated. Lee looked away and speared more bread.

Gelert lifted his head from his drink, and within a few seconds—neither too quickly nor too slowly—Konrad Egli made his way over to their banquette table. Herr Egli was a great, gray, craggy block of a man, like a small Alp; forty years the master of this house and long past being ruffled by anything, even the presence of the absolute master of an entire otherworld. Mortal kings and princesses, and rock stars and politicos and chairmen of the board, all the lesser sorts of royalty, had been dining in his restaurant for years. He treated them all with the same benevolent, ruthless hospitality that he bestowed on first-timers just in off the street, and nothing any of them said or did ever seemed t

o catch him off guard. Now Herr Egli leaned down beside Gelert—not too far: even sitting on the floor, Gelert was tall enough to have to look slightly downward at Lee—and nodded at the empty Waterford bowl.

“Another one, madra?”

“Please.”

“Konni,” Lee said, keeping her voice low, “does he come here often?” She nodded at the far side of the room, where jocund voices were rising in discreet merriment at some carefully witty remark.

Herr Egli shook his head. “A few times a year. Always business dinners, or lunches.” He glanced over his shoulder for a second, then added with a smile and a fatherly scowl, “His guests—they never seem to finish what they order.”

Lee smiled wryly. Herr Egli took his role of patron seriously, and was not above scolding his favorite customers in friendly fashion if they seemed to need it. “You notice,” she said in mock-daughterly respect, “that I ate all my spinach.”

“Good girl. Another glass of wine?”

“Yes, Konni, thank you.”

He picked up her wineglass and Gelert’s bowl and carried them away to the bar; then, at the thump the inner front door made when the outer door was opened, turned to greet an arriving guest. Lee dunked another chunk of bread for Gelert and offered it to him. He accepted it with eyes half closed, a sybarite’s lazy look, and thumped his tail gently on the wine-colored carpet as he chewed. “I’m glad we came,” he said. “Even if you think you can’t afford it.”

“Excuse me,” Lee said, ” you’re paying for this one, you said.”

Gelert grinned, exhibiting many sharp white fangs. “But Lee, my portfolio—”

“—needs a forklift to pick it up. I’d ask you how you do it, except I’d be afraid we’d have the Securities and Exchange Commission after us about ten minutes later. And anyway, you’re right, we do deserve it. We worked our butts off on that case. Here at least we can have dinner without the people from the local TV stations shoving cameras in our faces. So I will ever so gracefully, just this once, let you pay.”

The Book of Night With Moon

The Book of Night With Moon A Wind From the South

A Wind From the South A Wizard Abroad, New Millennium Edition

A Wizard Abroad, New Millennium Edition Lior and the Sea

Lior and the Sea Uptown Local and Other Interventions

Uptown Local and Other Interventions High Wizardry New Millennium Edition

High Wizardry New Millennium Edition Games Wizards Play

Games Wizards Play Wizard's Holiday, New Millennium Edition

Wizard's Holiday, New Millennium Edition So You Want to Be a Wizard, New Millennium Edition

So You Want to Be a Wizard, New Millennium Edition The Door Into Sunset

The Door Into Sunset To Visit the Queen

To Visit the Queen A Wizard Abroad

A Wizard Abroad Not on My Patch

Not on My Patch The Door Into Shadow

The Door Into Shadow The Door Into Fire

The Door Into Fire A Wizard Alone New Millennium Edition

A Wizard Alone New Millennium Edition The Tale of the Five Omnibus

The Tale of the Five Omnibus The Wizard's Dilemma, New Millennium Edition

The Wizard's Dilemma, New Millennium Edition The Big Meow

The Big Meow Wizards at War, New Millennium Edition

Wizards at War, New Millennium Edition Interim Errantry

Interim Errantry Omnitopia: Dawn

Omnitopia: Dawn High Wizardry

High Wizardry Spider-Man: The Venom Factor Omnibus

Spider-Man: The Venom Factor Omnibus Spider-Man: The Venom Factor

Spider-Man: The Venom Factor Seaquest DSV

Seaquest DSV How Lovely Are Thy Branches

How Lovely Are Thy Branches So You Want to Be a Wizard

So You Want to Be a Wizard Midnight Snack and Other Fairy Tales

Midnight Snack and Other Fairy Tales Stealing the Elf-King's Roses

Stealing the Elf-King's Roses Interim Errantry 2: On Ordeal

Interim Errantry 2: On Ordeal Raetian Tales 1: A Wind from the South

Raetian Tales 1: A Wind from the South Starrise at Corrivale h-1

Starrise at Corrivale h-1 The Wizard's Dilemma

The Wizard's Dilemma Sand and Stars

Sand and Stars How Lovely Are Thy Branches: A Young Wizards Christmas

How Lovely Are Thy Branches: A Young Wizards Christmas On Her Majesty's Wizardly Service fw-2

On Her Majesty's Wizardly Service fw-2 X-COM: UFO Defense

X-COM: UFO Defense Star Trek: The Original Series: Rihannsu, Book 5: The Empty Chair

Star Trek: The Original Series: Rihannsu, Book 5: The Empty Chair seaQuest DSV: The Novel

seaQuest DSV: The Novel Stealing the Elf-King's Roses: The Author's Cut

Stealing the Elf-King's Roses: The Author's Cut Not On My Patch: a Young Wizards Hallowe'en Story

Not On My Patch: a Young Wizards Hallowe'en Story A Wizard Alone yw[n&k-6

A Wizard Alone yw[n&k-6 The Bloodwing Voyages

The Bloodwing Voyages Games Wizards Play (Young Wizards Series)

Games Wizards Play (Young Wizards Series) The Book of Night with Moon fw-1

The Book of Night with Moon fw-1 My Enemy My Ally

My Enemy My Ally Dark Mirror

Dark Mirror Star Trek: The Original series: Rihannsu: The Bloodwing Voyages

Star Trek: The Original series: Rihannsu: The Bloodwing Voyages Deep Wizardry yw[n&k-2

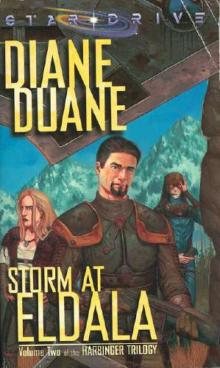

Deep Wizardry yw[n&k-2 Storm at Eldala h-2

Storm at Eldala h-2