- Home

- Diane Duane

The Big Meow Page 17

The Big Meow Read online

Page 17

“I wouldn’t bet on it,” Siffha’h said, and closed her eyes.

A sudden odd silence fell over the intersection as all the cars’ electrical systems failed in unison, for perhaps a mile in every direction.

The silence didn’t last more than a few moments: all around the traffic lights, drivers started getting out of their cars, pulling the vehicles’ hoods open, staring into the complex innards in complete bemusement, and (in some cases) exercising their vocabularies most creatively. But Arhu paid them no mind. In mid-intersection, he sat himself down, curled his tail around his toes, and stared in an unfocused-looking way at the cracked concrete there.

Rhiow didn’t have anything of the Eye herself, but to a watching wizard, the influences involved in its use could obscurely be glimpsed. For a few seconds, the imagery of previous hours whirled around Arhu as he felt about with his mind for the specific moments of past time that were needed. He overshot a bit at first. Filmy cars seemed to run over or through him at high speed, gauzy pedestrians jittered back and forth in the background; the memories of recent days and nights alternately spotlighted or shadowed Arhu. He didn’t move, not even his tail twitching, as the imagery faded, went unchangingly dark around him. And then he looked up, gazing down Hollywood Boulevard.

“There,” Arhu said.

They watched her come, moving through and past the brief here-and-now traffic jam as if it wasn’t there: but then again, last night, it hadn’t been. Down the white line she came, exactly as described. The revenant was a thin, pale apparition in the broad sunlight of day, and hard to see; but there was no mistaking her. She was tall and elegantly dressed and empty-eyed, walking with a stately and icy precision, her eyes seeming fixed on some goal that the people around her had given up their right to see. The expression of cold-set scorn on the queen-ehhif’s face, and the feeling of revulsion and rejection that flowed from her, gave Rhiow a chill down her back.

She glanced up and saw with some surprise that the Silent Man’s eyes were fixed, not on Arhu or the traffic jam, but the remembered vision of the night before. But then he was here, Rhiow thought. That alone could make it possible for him to see an induced recurrence.

Possibly feeling Rhiow’s regard on him, the Silent Man glanced down at her. That’s a good trick, he said.

“We’ll see if it’s going to be good enough,” Rhiow said. Closer and closer the vision came, straight down the white line, walking right through one of the live ehhif who was standing with his hands on his hips and staring at his stalled car in disgust. He got an odd look, that ehhif, and he shivered all over: in the mid-morning warmth, he took off his hat and mopped his brow as if suddenly sweating cold.

On the Lady in Black came, and stepped out into the intersection. Another second or three and she would walk right through Arhu. But he looked up, catching her eyes with his: and in mid-step she froze where she was.

In that instant the vision went sharp, clear and dark. Around her the pavement went black and wet; beyond her, night and streetlights could be seen. Rhiow didn’t move, for fear of distracting Arhu. But she looked closely at the Lady in Black. As ehhif went, Rhiow suspected that this particular queen would be considered extremely beautiful. Yet there was also something strange about her, a sense that the physical form she wore was as relatively unimportant as some item of clothing.

Rhiow looked harder, as Arhu was doing. He had gotten up now and stretched himself, and was walking around the queen-ehhif. Perhaps Rhiow caught a touch of his examination more directly, now, for as she looked at the ehhif’s shape, inside it, only half-seen, some odd force seemed to twist and writhe. What’s going on there? Rhiow wondered, her ears starting to go back. It’s as if –

She’s not really there? Arhu said silently, pausing to look up at the woman-shape from behind. He was bristling, the hair on his back all spiked up, and his tail was starting to fluff. Good guess. No scent, Rhi. She’s a shell. She’s been soulsplit.

Rhiow growled softly in her throat, angry and unnerved to have her and Hwaith’s suspicions independently confirmed. A few ways did exist to denature a body’s connection to its soul while the body was still living – not exactly a severance, but the next best thing, exempting the soul from passing along the consequences of its actions to the body in which it belonged. All these methods were dangerous, and except under very specific circumstances, all of them were illegal for wizards to use, either on other beings or on themselves. There were, of course, some ways besides wizardry to produce the same effects. Either way, the hapless practitioners tended not to stay alive long enough to spread information about the techniques very widely. But where soulsplitting was being employed, there were also usually other closely affiliated abuses of power to be found: and all of them were favorite tools of Sa’rráhh’s, when the Lone One thought she could trick some poor mortal creature into using them.

Is her body still alive, do you think? Hwaith said.

Don’t know, Arhu said. She sure doesn’t care. This soul’s completely taken up with thoughts of what she’s warning us poor bystanders about. His tail was lashing. And she’s enjoying the thoughts, let me tell you. She really hates everyone and everything here, and she just can’t wait to see this whole state fall right off into the Pacific.

Rhiow hardly found that surprising. Many beings who underwent soulsplitting did so because they thought that liberating the soul from the body while still scheduled to be alive would allow them access to some “higher”, purer, less emotion-dominated state of being. But all too often matters went the other way entirely, usually because the creature initiating the split didn’t fully understand the deeper reaches of the relationship between soul and body — the way the physical side of existence acted as a check on the less safe or sane urges of a spirit still connected, however tenuously, to physical timeflow and its consequences. Arhu, Rhiow said, is it safe to query her? For us, and for her connection to her body? Whatever state that might be in…

Arhu walked back around in front of the Lady in Black, watching her closely, and sat down again. I’m holding this revenance out of the timeflow for the moment, he said. It’s probably safe enough to ask her a few questions. But I can’t keep Seeing her this way for long: and even if I could, it might not be smart. Something else is watching her too, Rhi. Whatever it is, it’s inside time, and shouldn’t have any perception of this frozen moment. But I’d rather not press my luck.

All right. Ask her: who is the Great Old One?

Arhu said nothing aloud, merely looked at the queen-ehhif’s apparition. She spoke no word in response, moved not at all. But at a long chilly remove, as if it were being bounced back through several stages of some immaterial relay, the answer came: He is the one from outside, older than all Gods: their inverse, dwelling in the Void. He is the darkness before any word, and the silence into which all words spoken must die. He is the End.

Rhiow licked her nose. Urruah, now sitting by her, looked out at Arhu. Ask her, Urruah said, who is the Black Leopard?

Another long silence: longer this time, Rhiow thought. He is Tepeyollotl Night-Eater, Lord of the Beasts of the Dark, the answer came back, who is called into time to devour all things: and to the darkness beyond time and timelessness he will return when all is devoured. He is the Herald of the End.

Rhiow and Urruah looked at each other. Each of them could feel the Whisperer, silent for the moment, listening through their ears and minds: and they could feel the tension in Her as if it were their own.

Rhi, Arhu said, can you feel something in this neighborhood watching this? Not that close by. Not actually taking an interest as yet. But it might –

Urruah looked out at the intersection, his tail waving slowly from side to side, his ears down. Ask her, what is the meaning of the sacrifice that has been made?

An even longer pause this time. It is the opening of the way into the realities that are fouled with life. It is life spilled out to enable the entry of the Great Old One into the worlds he will rule and

destroy. It is the beginning of the End.

Rhiow stared at Urruah, the fur going up on her back…as, on some other level of reality, the Whisperer’s was doing. And Hwaith, standing by Rhiow and Urruah now, looked out at Arhu. Ask her, he said: where did you die?

Rhiow looked at Hwaith in shock. And this time there was no delay whatever in the answer. I have not died. I can never die! Yet I am done with the world of bodies, one with the Black One forever, safe in His darkness! It was almost a shout of triumph, the first answer holding any passion that this image of the Lady in Black had produced. Yet – was there fear in that voice, too?

— and beneath it, so faint that Rhiow’s ears twitched forward as if to hear it better, a faint desperate cry like the mewl of a kitten trapped down a sewer: Laurel –

And the fur abruptly stood up all over Arhu. That’s enough! he said, hurriedly backing away from the Lady in Black. On the instant, the rainy night that had seemed to cling about her was gone. She was a ghost again, pale in the hot sunlight, and moving again, walking down the centerline of Hollywood Boulevard, past them, around the corner, and up Highland past the Silent Man’s blue car. And then she was gone.

Arhu made his way back to the sidewalk and sat down there, still sidled. He started washing, and it was very much the composure-washing of someone eager to put himself to rights before their ehhif guest could see him.

What happened there? Hwaith said.

Arhu paused in his washing and shook his head as if someone had clouted him upside the ear. Whatever was listening…all of a sudden started listening a whole lot harder. If it’d heard much more, it could have realized who was looking at it, and from when. Not something we want anyone to know right now, I’d think.

He was unnerved. Rhiow put her head down, bumped heads with him, though she was unsure how much reassurance she could truly offer Arhu in a situation like this: she was unnerved enough herself. You did right, she said. There’s another spot we need to look at, down the street: but it can wait a little.

No, Arhu said. No, I’m all right. He shook his head hard, so that his ears rattled: when he looked up, a little of the normal insouciance was back.

This soulsplit, Hwaith said. How long ago would you say it happened?

Arhu’s tail twitched with uncertainty. Hard to say. That soul could last have been in a body as long as…two, maybe three weeks back –

Around the time the earthquakes started, perhaps? Hwaith said.

Arhu looked at him thoughtfully. Could be, said Arhu. It’ll take a little more checking to find out. We’ll need to go back up the hill and have another look at that spot where the gate’s trying to root. I didn’t have any idea, the first time, that we were going to find this connection…

Rhiow sat down by Siffha’h and tried to keep her own bristling under control. Wonderful, she thought. Another problem we didn’t need. For now the question arose: had the Lady in Black invoked this unsavory state of existence of her own free will, or had she had it wished on her? If she had, she had to be helped out of it. If the soulsplit had been her own idea, she still had to be offered the opportunity to remake the choice. Assuming her body isn’t already quietly decomposing somewhere up in the hills, Rhiow thought, or being digested inside any number of coyotes. Why in Iau’s name do ehhif seem so eager to do this kind of thing to themselves?…

Meanwhile, here they all stood in the sunshine, with the ehhif of the past going about their business in their fat solid shining cars, and in the big red trolleys that passed by with a cheerful clangor of bells when pedestrians threatened to get in their way, or some auto turned across an intersection in a trolley’s path. The fronds on the palm trees off to their right rustled and glinted in the sun, and everything nonetheless seemed very unreal… especially with the direct experience of the Whisperer’s unease just a few minutes before. Rhiow let out a long breath. “Come on,” she said to Arhu, “get yourself unsidled: we’ve got to work out what to do next. Siffha’h – “

Siffha’h glanced down the road. Barely a second later, one of the engines in one of the cars some ways back in the traffic jam turned over. Other drivers, noticing, got back into their cars; within moments, more and more engines were revving all up and down the road.

Siffha’h got up then, stretched, and turned and walked away from the intersection. Behind her, the lights changed to green, and gradually traffic on Hollywood Boulevard started moving again. Behind one of the palm trees, Arhu came out of invisibility and wandered out to join the others.

The Silent Man watched him as Siffha’h went over to bump noses with him. So would someone tell me what that was all about? he said.

Rhiow was trying to figure out just how to do that, and how much to tell. “Half a moment,” she said. “I still have to finish debriefing our two youngsters. Was there somewhere else we were going first?”

Down by the Chinese – that other address you were interested in. It’s only a block or so.

“Let’s head down there, then,” Rhiow said.

They walked down Hollywood Boulevard, past the frontage of the hotel. It was a pleasant stroll in the sunshine, and amusing enough because of the ehhif they passed, who looked with utter fascination, sometimes with laughter, at the procession: the little man in dapper gray with a white cat riding on his shoulder, surrounded by a bodyguard of four more – the gray tabby in the lead, two black cats and a small white calico-patched tom strolling on either side of him, and another calico-patched white bringing up the rear. Cars on the Boulevard, having been sitting still for the better part of fifteen minutes, now actually slowed down again to watch them all pass by. Rhiow flirted her tail in wry comment as they made their way along the Hollywood Hotel’s palm-lined front terraces. To Arhu she said, Now tell me: what did you find up by Laurel and Highland Trail that left you so on edge?

The gate’s sunk a root there, all right, Arhu said, silent. But not deep: not yet. He sounded unusually grim.

Then what’s the trouble?

Someone died there, Rhi. An ehhif. Not long ago.

Siffha’h came up alongside her twin and put her tail over his back as they walked. The gate-root was tunneling straight down into where that life spilled, she said, sure as a seedling drilling down for water.

Spilled? Rhiow said. Actual bloodshed?

Siffha’h wrinkled her nose in disgust and distress. No question. A Person with no nose could have smelled it.

And a Person with the Eye, Arhu said, could see it.

That explained Arhu’s grimness well enough. Nearly murdered with his littermates when hardly more than a few weeks old, Arhu’s relationship with death was a thorny one, and probably would be for some lives yet: that kind of trauma could take a good while to move through. And —

Laurel, Rhiow said. She said “Laurel” —

Arhu looked at her, both angry and confused. No, he said. No matter what she says, I’m not sure the Lady in Black is really dead. And anyway, she’s not the one I saw killed.

Rhiow stared at him. Are you sure?

The Eye doesn’t lie: not when it’s looking back. Forward’s another story. The dead ehhif up on Laurel was a tom… But he still looked confused. Trouble is, Rhi…what we all saw, just now, still smells to me of that death up the hill.

They all walked on to the next intersection, where the sidewalk bent around a gardeny area marking the end of the hotel’s property. I could make the predictable joke about tongues, said the Silent Man, glancing down Orchid Street to see if any traffic was coming. But you’d probably thank me not to. What did Patches here find?

“We think,” Rhiow said, “perhaps a murder.”

Is that so.

Rhiow looked up in surprise at the sudden intense interest in the Silent Man’s voice. His eyes were on her, and they were suddenly much more alert than they had been.

“It’s early to tell, yet,” Urruah said from where he’d fallen in beside Rhiow. “Always a mistake to start theorizing before you’ve finished examining the ev

idence carefully….”

The Silent Man smiled. Another student of the Master, he said. Well, this makes the spot we’re about to visit a little more interesting.

“Why?” Rhiow said.

But the Silent Man just shook his head as they crossed Orchid. Rhiow wasn’t given much time to press the issue, for as they came up onto the curb of the far corner, Urruah stood stock still for a moment at something he saw…then broke into a run. Tourists and business people and casual strollers on that sidewalk looked with surprise or amusement at the big gray tabby that ran helter-skelter down among them, stopping in front of what seemed from this end of the street to be some kind of big empty plaza. Urruah stood staring into that space as intently as if it were some kind of delicatessen.

The Silent Man glanced down at Rhiow, a wry look. Tell me he’s a film fan, he said, in the tone of an ehhif now prepared to believe just about anything.

“There are a fair number of us,” Hwaith said. “More than you might suspect…”

The Silent Man reached up to rub Sheba behind the ears as they walked after Urruah. Now why in the world would you be interested in the movies?

“Because we appreciate a good story as much as you do,” Hwaith said. “Even when it’s full of all that boring human stuff.”

The Silent Man looked just briefly nonplussed. And the glance Hwaith threw Rhiow then was so wicked that, despite her concerned mood, she still had to stifle a laugh. She was still working at retaining her composure by the time they all caught up with Urruah, or rather, with the spot where he had been standing.

There before them lay a wide space filled with strange differently-colored patches of concrete. Curved walls decorated with fanciful-looking flowery sculptures embraced this forecourt on either side, ending in two archways peaked with odd prickly-topped towers; each was sheathed in greened copper, and flared up into peculiar spiky crowns. At the rear of the concrete-filled plaza were bronze doors guarded by a couple of huge statues of what Rhiow at first took to be houiff — though there was something leonine about them as well, so that she was strangely reminded of the statues of Hhu’au and Sef outside the New York Public Library. Above the doors, done on a huge plaque of gray stone, was a massive curling carving of some kind of fireworm; and above it all, borne up on coral-colored columns, rose yet another high sloping copper roof with yet more spiky ironmongery cornices at the corners.

The Book of Night With Moon

The Book of Night With Moon A Wind From the South

A Wind From the South A Wizard Abroad, New Millennium Edition

A Wizard Abroad, New Millennium Edition Lior and the Sea

Lior and the Sea Uptown Local and Other Interventions

Uptown Local and Other Interventions High Wizardry New Millennium Edition

High Wizardry New Millennium Edition Games Wizards Play

Games Wizards Play Wizard's Holiday, New Millennium Edition

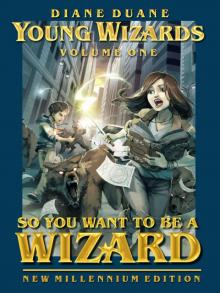

Wizard's Holiday, New Millennium Edition So You Want to Be a Wizard, New Millennium Edition

So You Want to Be a Wizard, New Millennium Edition The Door Into Sunset

The Door Into Sunset To Visit the Queen

To Visit the Queen A Wizard Abroad

A Wizard Abroad Not on My Patch

Not on My Patch The Door Into Shadow

The Door Into Shadow The Door Into Fire

The Door Into Fire A Wizard Alone New Millennium Edition

A Wizard Alone New Millennium Edition The Tale of the Five Omnibus

The Tale of the Five Omnibus The Wizard's Dilemma, New Millennium Edition

The Wizard's Dilemma, New Millennium Edition The Big Meow

The Big Meow Wizards at War, New Millennium Edition

Wizards at War, New Millennium Edition Interim Errantry

Interim Errantry Omnitopia: Dawn

Omnitopia: Dawn High Wizardry

High Wizardry Spider-Man: The Venom Factor Omnibus

Spider-Man: The Venom Factor Omnibus Spider-Man: The Venom Factor

Spider-Man: The Venom Factor Seaquest DSV

Seaquest DSV How Lovely Are Thy Branches

How Lovely Are Thy Branches So You Want to Be a Wizard

So You Want to Be a Wizard Midnight Snack and Other Fairy Tales

Midnight Snack and Other Fairy Tales Stealing the Elf-King's Roses

Stealing the Elf-King's Roses Interim Errantry 2: On Ordeal

Interim Errantry 2: On Ordeal Raetian Tales 1: A Wind from the South

Raetian Tales 1: A Wind from the South Starrise at Corrivale h-1

Starrise at Corrivale h-1 The Wizard's Dilemma

The Wizard's Dilemma Sand and Stars

Sand and Stars How Lovely Are Thy Branches: A Young Wizards Christmas

How Lovely Are Thy Branches: A Young Wizards Christmas On Her Majesty's Wizardly Service fw-2

On Her Majesty's Wizardly Service fw-2 X-COM: UFO Defense

X-COM: UFO Defense Star Trek: The Original Series: Rihannsu, Book 5: The Empty Chair

Star Trek: The Original Series: Rihannsu, Book 5: The Empty Chair seaQuest DSV: The Novel

seaQuest DSV: The Novel Stealing the Elf-King's Roses: The Author's Cut

Stealing the Elf-King's Roses: The Author's Cut Not On My Patch: a Young Wizards Hallowe'en Story

Not On My Patch: a Young Wizards Hallowe'en Story A Wizard Alone yw[n&k-6

A Wizard Alone yw[n&k-6 The Bloodwing Voyages

The Bloodwing Voyages Games Wizards Play (Young Wizards Series)

Games Wizards Play (Young Wizards Series) The Book of Night with Moon fw-1

The Book of Night with Moon fw-1 My Enemy My Ally

My Enemy My Ally Dark Mirror

Dark Mirror Star Trek: The Original series: Rihannsu: The Bloodwing Voyages

Star Trek: The Original series: Rihannsu: The Bloodwing Voyages Deep Wizardry yw[n&k-2

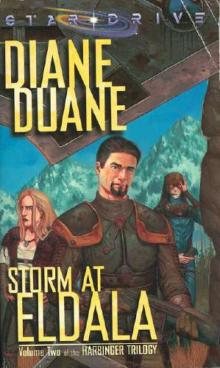

Deep Wizardry yw[n&k-2 Storm at Eldala h-2

Storm at Eldala h-2